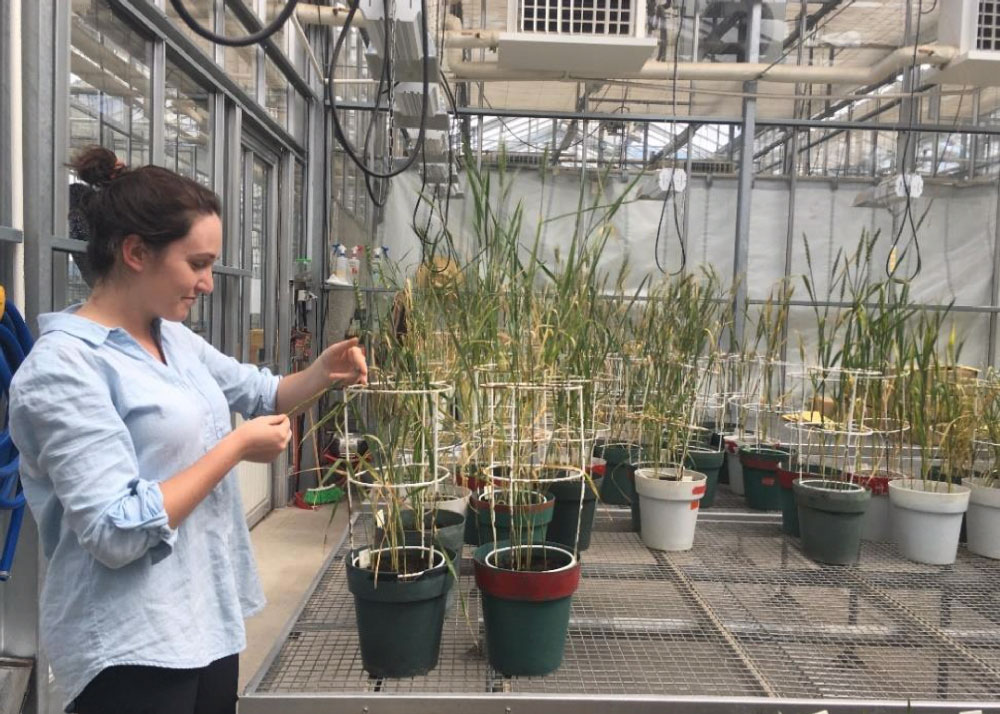

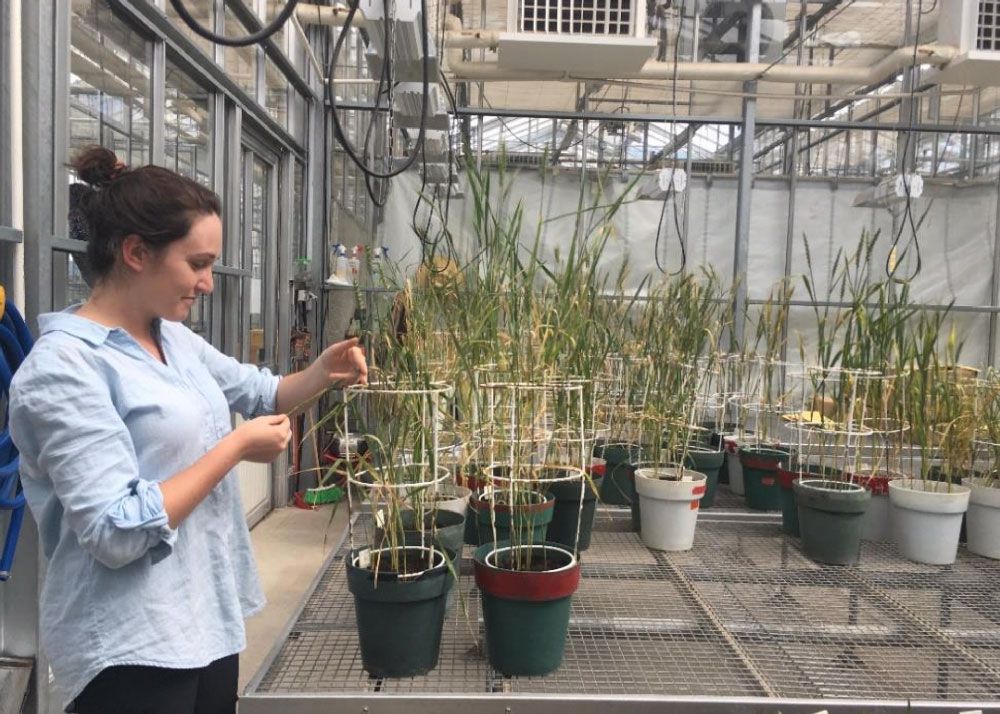

University of Queensland student researches tan spot resistance in wheat at CIMMYT

This story, part of a series on the international agricultural research projects of recipients of the Crawford Fund’s International Agricultural Student Award, was originally posted on the Crawford Fund blog.

In 2018, Tamaya Peressini, from the Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation (QAAFI), a research institute of the University of Queensland (UQ), travelled to CIMMYT in Mexico as part of her Honours thesis research, focused on a disease called tan spot in wheat.

Tan spot is caused by the pathogen Pyrenophora triciti-repentis (Ptr) and her project aimed to evaluate the resistance of tan spot in wheat to global races to this pathogen.

“The germplasm I’m studying for my thesis carries what is known as adult plant resistance (or APR) to tan spot, which has demonstrated to be a durable source of resistance in other wheat pathosystems such as powdery mildew,” Peressini said.

Tan spot is prevalent worldwide, and in Australia causes the most yield loss out of the foliar wheat diseases. In Australia, there is only one identified pathogen race that is prevalent, called Ptr Race 1. For Ptr Race 1, the susceptibility gene Tsn1 in wheat is the main factor that results in successful infection in Ptr strains that carry Toxin A. However, globally it is a more difficult problem, as there are seven other pathogen races that consist of different combinations of necrotrophic toxins. Hence, developing cultivars that are multi-race resistant to Ptr presents a significant challenge to breeders, as multiple resistant genes would be required for resistance to other pathogens.

“At CIMMYT, I evaluated the durability of APR I identified in plant material in Australia by inoculating with a local strain of Ptr and also with a pathogen that shares ToxA: Staganospora nodorum,” Peressini explained.

“The benefit of studying this at CIMMYT was that I had access to different strains of the pathogen which carry different virulence factors of disease, I was exposed to international agricultural research and, importantly, I was able to create research collaborations that would allow the APR detected in this population to have the potential to reach developing countries to assist in developing durably resistant wheat cultivars for worldwide deployment.”

Recent work in Dr Lee Hickey’s laboratory in Queensland has identified several landraces from the Vavilov wheat collection that exhibited a novel resistance to tan spot known as adult plant resistance (APR). APR has proven to be a durable and broad-spectrum source of resistance in wheat crops, namely with the Lr34 gene which confers resistance to powdery mildew and leaf stem rust of wheat.

“My research is focused on evaluating this type of resistance and identifying whether it is resistant to multiple pathogen species and other races of Ptr. This is important to the Queensland region, as the northern wheat belt is significantly affected by tan spot disease. Introducing durable resistance genes to varieties in this region would be an effective pre-breeding strategy because it would help develop crop varieties that would have enhanced resistance to tan spot should more strains reach Australia. Furthermore, it may provide durable resistance to other necrotrophic pathogens of wheat,” Peressini said.

The plant material Peressini studied in her honors thesis was a recombinant inbred line (RIL) population, with the parental lines being the APR landrace — carries Tsn1 — and the susceptible Australian cultivar Banks — also carries Tsn1. To evaluate the durability of resistance in this population to other strains of Ptr, this material along with the parental lines of the population and additional land races from the Vavilov wheat collection were sent to CIMMYT for Tamaya to perform a disease assay.

“At CIMMYT I evaluated the durability of APR identified in plant material in Australia by inoculating with a local strain of Ptr and also with a pathogen that shares ToxA: Staganospora nodorum. After infection, my plant material was kept in 100 per cent humidity for 24 hours (12 hours light and 12 hours dark) and then transferred back to regular glasshouse conditions. At 10 days post infection I evaluated the resistance in the plant material.”

From the evaluation, the APR RIL line demonstrated significant resistance compared to the rest of the Australian plant material against both pathogens. The results are highly promising, as they demonstrate the durability of the APR for both pre-breeding and multi-pathogen resistance breeding. Furthermore, this plant material is now available for experimental purposes at CIMMYT, where further trials can validate how durable the resistance is to other necrotrophic pathogens and also be deployed worldwide and be tested against even more strains of Ptr.

“During my visit at CIMMYT I was able to immerse myself in the Spanish language and take part in professional seminars, tours, lab work and field work around the site. A highlight for me was learning to prepare and perform toxin infiltrations for an experiment comparing the virulence of different strains of spot blotch,” Peressini said.

“I also formed valuable friendships and research partnerships from every corner of the globe and had valuable exposure to the important research underway at CIMMT and insight to the issues that are affecting maize and wheat growers globally. Of course, there was also the chance to travel on weekends, where I was able to experience the lively Mexican culture and historical sites – another fantastic highlight to the trip!”

“I would like to thank CIMMYT and Dr Pawan Singh for hosting me and giving the opportunity to learn, grow and experience the fantastic research that is performed at CIMMYT and opportunities to experience parts of Mexico. The researchers and lab technicians were all so friendly and accommodating. I would also like to thank my supervisor Dr Lee Hickey for introducing this project collaboration with CIMMYT. Lastly, I would like to thank the Crawford Fund Queensland Committee for funding this visit; not only was I able to immerse myself in world class plant pathology research, I have been given valuable exposure to international agricultural research that will give my research career a boost in the right direction,” Peressini concluded.

Building on a more than 40-year-old partnership in crop modelling and physiology, a two-day workshop organized by CIMMYT and Australia’s

Building on a more than 40-year-old partnership in crop modelling and physiology, a two-day workshop organized by CIMMYT and Australia’s  SYDNEY, Australia, October 9 (CIMMYT) – A recent gathering of more than 600 international scientists highlighted the complexity of wheat as a crop and emphasized the key role wheat research plays in ensuring global food security now and in the future.

SYDNEY, Australia, October 9 (CIMMYT) – A recent gathering of more than 600 international scientists highlighted the complexity of wheat as a crop and emphasized the key role wheat research plays in ensuring global food security now and in the future.

Sanjaya Rajaram is the 2014 World Food Prize laureate for scientific research that led to an increase in world wheat production by more than 200 million tons. Any views expressed are his own.

Sanjaya Rajaram is the 2014 World Food Prize laureate for scientific research that led to an increase in world wheat production by more than 200 million tons. Any views expressed are his own.

CIMMYT Director General Martin Kropff speaks on the topic of ‘Wheat and the role of gender in the developing world’ prior to the 2015 Women in Triticum Awards at the Borlaug Global Rust Initiative Workshop in Sydney on 19 September.

CIMMYT Director General Martin Kropff speaks on the topic of ‘Wheat and the role of gender in the developing world’ prior to the 2015 Women in Triticum Awards at the Borlaug Global Rust Initiative Workshop in Sydney on 19 September.