Scientists seek key to boost yields, ensure future food supply

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) — Crop genetic gains remain too low, and international scientists are making a concerted effort to determine how best to increase yields to ensure there is enough food to feed everyone on the planet by 2050.

The complex task of increasing genetic gains – the amount of increase in performance achieved per unit time through artificial selection – involves considering many variables, including genotypes and phenotypes – selecting crop varieties with desired gene traits and considering how well they perform in a given environment.

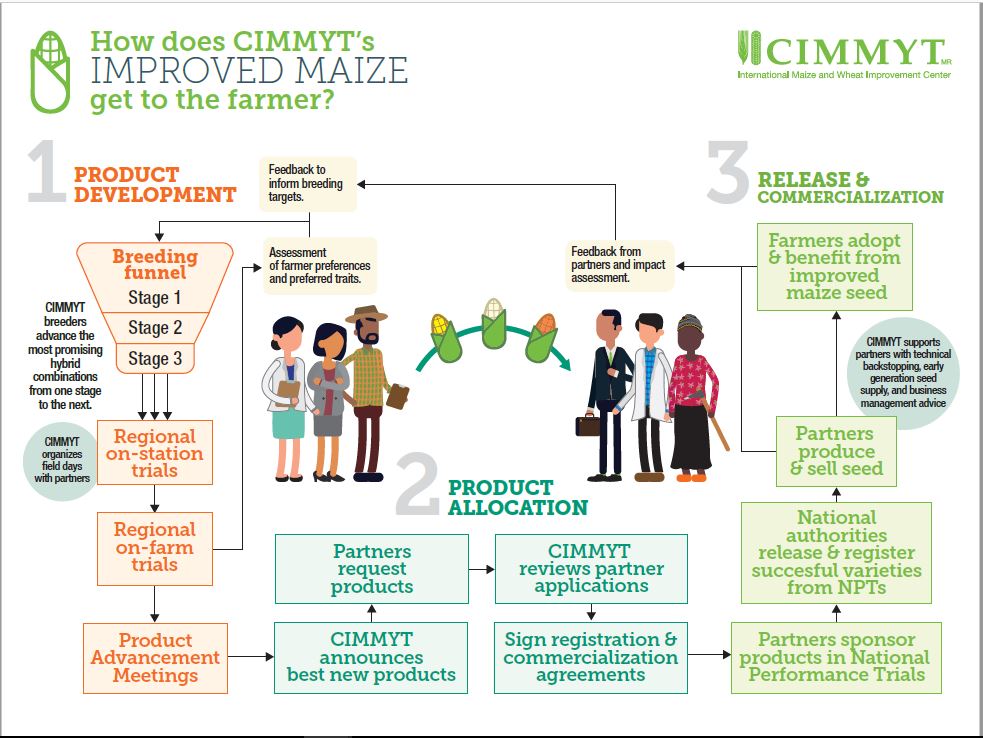

Two new research papers by scientists at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and partners at Australia’s University of Queensland and Spain’s University of Barcelona published in “Trends in Plant Science” highlight some of the best available tools and strategies for meeting the challenge.

Currently, crop breeding methods and agronomic management put annual productivity increases at 1.2 percent a year, but to ensure food security for future generations, productivity should be at 2.4 percent a year.

By 2050, the United Nations projects that the current global population of 7.6 billion will grow to more than 9.8 billion, making yield increases vital.

The results of grain yield increases each year are a function of the length of the breeding process, the accuracy of which breeders can estimate the potential of new germplasm, the size of the breeding program, the intensity of selection, and the genetic variation for the trait of interest.

“Reducing the length of the breeding process is the fastest way for breeders to increase their gains in grain yield per year,” said HuiHui Li, quantitative geneticist based at CIMMYT Beijing.

Speed breeding and other new techniques have the potential to double gains made by breeders some crops. Speed breeding protocols enable six generations of crops to be generated within a single year, compared to just two generations using traditional protocols.

Pioneered by scientist Lee Hickey at University of Queensland, speed breeding relies on continuous light to trick plants into growing faster, which means speed breeding can only be undertaken in a controlled environment.

Tapping into larger populations increases the probability of identifying superior offspring, but breeding is an expensive and time consuming process due to the variables involved.

One challenge scientists face is high-throughput field phenotyping, which involves characterising hundreds of plants a day to identify the best genetic variation for making new varieties. New phenotyping tools can estimate key traits such as senescence, reducing the time of data collection from a day or more to less than an hour.

“If breeders could reduce the cost of phenotyping, they can reallocate resources towards growing larger populations,” said Mainassara Zaman-Allah, a senior scientist at CIMMYT-Zimbabwe and a key contributor to the paper “Translating High Throughput Phenotyping into Genetic Gain.”

“Limitations on phenotyping efficiency are considered a key constraint to genetic advance in breeding programs,” said Mike Olsen, maize upstream trait pipeline coordinator with CIMMYT, based in Nairobi. “New phenotyping tools to more efficiently measure required traits will play an important role in increasing gains.”

New tools and techniques can only help contribute to food security if they are easily available and adopted. The CGIAR Excellence in Breeding Platform, launched in 2017, will play a pivotal role in ensuring these new tools reach breeding programs targeting the developing world.

Related:

Translating high-throughput phenotyping into genetic gain