CGIAR webinar unleashes multidisciplinary approach to climate change and plant health

Evidence of enormity and immediacy of the challenges climate change poses for life on earth seems to pour in daily. But important gaps in our knowledge of all the downstream effects of this complex process remain. And the global response to these challenges is still far from adequate to the job ahead. Bold, multi-stakeholder, multidisciplinary action is urgent.

Mindful of this, the first event in Unleashing the Potential of Plant Health, a CGIAR webinar series in celebration of the UN-designated International Year of Plant Health, tackled the complicated nexus between climate change and plant health. The webinar, titled “Climate change and plant health: impact, implications and the role of research for adaptation and mitigation,” convened a diverse panel of researchers from across the CGIAR system and over 900 audience members and participants.

In addition to exploring the important challenges climate changes poses for plant health, the event explored the implications for the wellbeing and livelihoods of smallholder farming communities in low- and middle- income countries, paying special attention to the gender dimension of both the challenges and proposed solutions.

The event was co-organized by researchers at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) and the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (icipe).

The overall webinar series is hosted by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), the International Potato Center (CIP), the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) and the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). It is sponsored by the CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition (A4NH), the CGIAR Gender Platform and the CGIAR Research Program on Roots, Tubers and Bananas (RTB).

This is important

The stakes for the conversation were forcefully articulated by Shenggen Fan, chair professor and dean of the Academy of Global Food Economics and Policy at China Agricultural University and member of the CGIAR System Board. “Because of diseases and pests, we lose about 20-40% of our food crops. Can you imagine how much food we have lost? How many people we could feed with that lost food? Climate change will make this even worse,” Fan said.

Such impacts, of course, will not be evenly felt across geographic and social divides, notably gender. According to Jemimah Njuki, director for Africa at IFPRI, gender and household relationships shape how people respond to and are impacted by climate change. “One of the things we have evidence of is that in times of crises, women’s assets are often first to be sold and it takes even longer for them to be recovered,” Njuki said.

Shifting risks

When it comes to understanding the impact of climate change on plant health “one of our big challenges is to understand where risk will change,” said Karen Garrett, preeminent professor of plant pathology at the University of Florida,

This point was powerfully exemplified by Henri Tonnang, head of Data Management, Modelling and Geo-information Unit at icipe, who referred to the “unprecedented and massive outbreak” of desert locusts in 2020. The pest — known since biblical times — has reemerged as a major threat due to extreme weather events driven by sea level rise.

Researchers highlighted exciting advancements in mapping, modelling and big data techniques that can help us understand these evolving risks. At the same time, they stressed the need to strengthen cooperation not only among the research community, but among all the stakeholders for any given research agenda.

“The international research community needs to transform the way it does research,” said Ana María Loboguerrero, research director for Climate Action at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT. “We’re working in a very fragmented way, sometime inefficiently and with duplications, sometimes acting under silos… It is difficult to deliver end-to-end sustainable and scalable solutions.”

Time for a new strategy

Such injunctions are timely and reaffirm CGIAR’s new strategic orientation. According to Sonja Vermeulen, the event moderator and the director of programs for the CGIAR System Management Organization, this strategy recognizes that stand-alone solutions — however brilliant — aren’t enough to make food systems resilient. We need whole system solutions that consider plants, animals, ecosystems and people together.

Echoing Fan’s earlier rallying cry, Vermeulen said, “This is important. Unless we do something fast and ambitious, we are not going to meet the Sustainable Development Goals.”

Register for the other webinars in the series

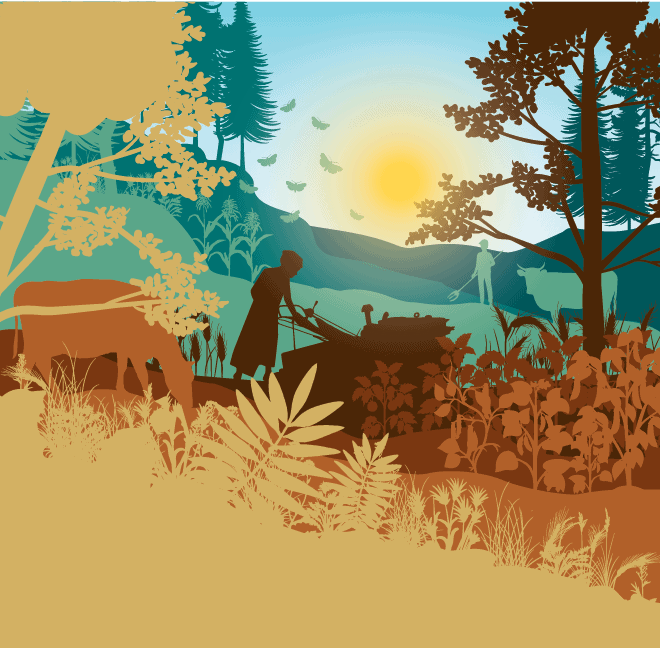

Cover photo: All farmers are susceptible to extreme weather events, and many are already feeling the effects of climate change. (Photo: N. Palmer/CIAT)

The UN has designated 2020 as the International Year of Plant Health. CGIAR Centers have significant scientific knowledge, extensive experience on the ground, and thought leadership that they can lend to the global discussion to advance awareness, collaboration, and scaling of needed interventions.

The UN has designated 2020 as the International Year of Plant Health. CGIAR Centers have significant scientific knowledge, extensive experience on the ground, and thought leadership that they can lend to the global discussion to advance awareness, collaboration, and scaling of needed interventions. Webinar 1 will discuss the anticipated impacts of climate change on plant health in smallholder systems, tackling how the occurrence, intensity, and frequency of biotic and abiotic stresses will change as a function of climate change. It will provide participants with information on the negative effects on plant health, in relation to food security, nutrition, environment, gender, and livelihoods, as well as on the role of research in providing support to global efforts to mitigate or adapt to climate change challenges for plant health.

Webinar 1 will discuss the anticipated impacts of climate change on plant health in smallholder systems, tackling how the occurrence, intensity, and frequency of biotic and abiotic stresses will change as a function of climate change. It will provide participants with information on the negative effects on plant health, in relation to food security, nutrition, environment, gender, and livelihoods, as well as on the role of research in providing support to global efforts to mitigate or adapt to climate change challenges for plant health.  Webinar 2 will highlight the importance of germplasm (phytosanitary) health in the prevention of transboundary pest and disease spread, as well as the propagation of clean planting material to be used locally. Experts will discuss the implications of poor germplasm practices on agricultural and food system sustainability, farmer livelihoods, and food and nutrition security. They will also examine how opportunities for greater workplace diversity in germplasm health hubs and gender-responsive programming could drive more inclusive sustainable development.

Webinar 2 will highlight the importance of germplasm (phytosanitary) health in the prevention of transboundary pest and disease spread, as well as the propagation of clean planting material to be used locally. Experts will discuss the implications of poor germplasm practices on agricultural and food system sustainability, farmer livelihoods, and food and nutrition security. They will also examine how opportunities for greater workplace diversity in germplasm health hubs and gender-responsive programming could drive more inclusive sustainable development.  Webinar 3 examines integrated approaches for sustainable management of transboundary diseases and crop pests and their implications for agri-food system sustainability, social inclusion and gender equity. Drawing on both successes and enduring challenges, experts will identify the potential benefits of more gender-responsive approaches to pest and disease control; more coordinated action by national, regional and global organizations; and lessons to be learned from successful animal health management.

Webinar 3 examines integrated approaches for sustainable management of transboundary diseases and crop pests and their implications for agri-food system sustainability, social inclusion and gender equity. Drawing on both successes and enduring challenges, experts will identify the potential benefits of more gender-responsive approaches to pest and disease control; more coordinated action by national, regional and global organizations; and lessons to be learned from successful animal health management.  Webinar 4 brings together scientists working at the intersection of environmental, human, and animal health. In this session, the experts will examine plant health and agriculture from a “One Health” approach — a collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary perspective that recognizes the health of people, animals, plants, and their environments as all closely connected. In this approach, agricultural practices and plant health outcomes both are determined by, and contribute to, ecological, animal, and human health.

Webinar 4 brings together scientists working at the intersection of environmental, human, and animal health. In this session, the experts will examine plant health and agriculture from a “One Health” approach — a collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary perspective that recognizes the health of people, animals, plants, and their environments as all closely connected. In this approach, agricultural practices and plant health outcomes both are determined by, and contribute to, ecological, animal, and human health.