Breaking Ground: Fatima Camarillo invests in education

It was clear to Fatima Camarillo Castillo from a young age that her future was in agriculture. She grew up on a farm in a small village in Zacatecas, Mexico, and recalls working in the fields alongside her father and siblings, helping with the harvests and milking the cows. And every year, her family ran into the same issue with their crops: droughts.

“Sometimes the harvest was okay, but sometimes we didn’t have any harvest at all,” says Camarillo. “For us that meant that, if we didn’t have enough harvest, then for the whole year my mother and father struggled to send us to school.”

But they did send her to school, and instead of escaping the persistent challenges that agriculture had presented her family in her young life, she was determined to solve them. “After elementary school we had to leave the farm to continue our education,” she explains. “I knew about all the challenges that small farmers face and I wanted to have an impact on them.”

To this day, Camarillo believes in the power of education. Her schooling took her all the way to the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), where she is now not only a researcher, but an educator herself. After her extensive study of plant breeding, genetics and wheat physiology, Camarillo gained a master’s degree from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and a PhD from Texas A+M University.

She was a part of CIMMYT’s fellowship program while pursuing her doctorate, and she joined the organization’s wheat breeding team shortly afterward. Camarillo now splits her time between wheat research and organizing the training activities for CIMMYT’s Global Wheat Program (GWP) wheat improvement course.

A special legacy

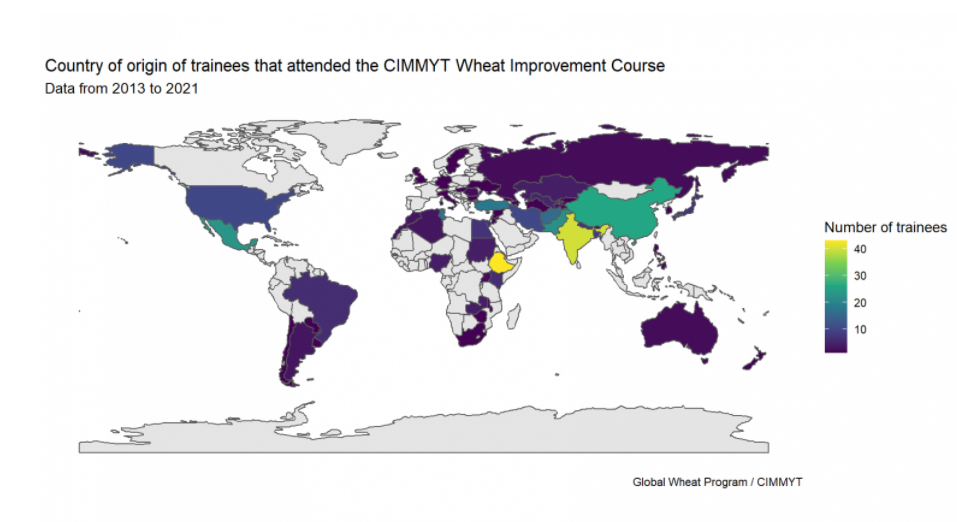

CIMMYT’s wheat improvement course is an internationally recognized program where scientists from national agricultural research programs (NARS) from around the world travel to CIMMYT Headquarters in Texcoco, Mexico, and then to Ciudad Obregón, for a 16-week training. Participants observe an entire breeding cycle and learn about the latest technologies and systems for breeding.

“A crucial component of having an impact on farmers is establishing good relationships with national programs, where all the germplasm that CIMMYT develops is going to go,” says Camarillo. “But at the same time, these partners need training. They need to know what is behind these varieties and the process for developing them, and we try to keep them updated with the vision, the current technologies and the breeding pipeline.”

The organization’s university-focused training programs are also special to Camarillo for many reasons, having participated in one of them herself. In fact, her first ever exposure to CIMMYT was through the annual Open Doors day which she attended during her first year of university, watching the breeders and scientists that would eventually become her colleagues give talks on germplasm development and distribution.

The courses also give students a chance to see all how their theoretical education can be applied in the real world. “When you are in graduate school you care a lot about data analysis and the most recent molecular tools,” says Camarillo. “But there is something else out there, the real problems outside. By taking the breeding program course you understand these challenges and situations.”

Camarillo remembers being struck by the thought that something that happens in a research station in Mexico can have an impact on the whole world. “CIMMYT cares about how other countries will adopt new varieties, it’s not just about developing germplasm for the sake of it,” she explains. “We’re interested in how new varieties are going to reach the farmers who need them, and for that, training is essential.”

“At the end of the day, these researchers are the ones who will help us evaluate germplasm. If they’re well trained, the efficiency of the whole process will increase.”

Keeping an eye on the breeding pipeline

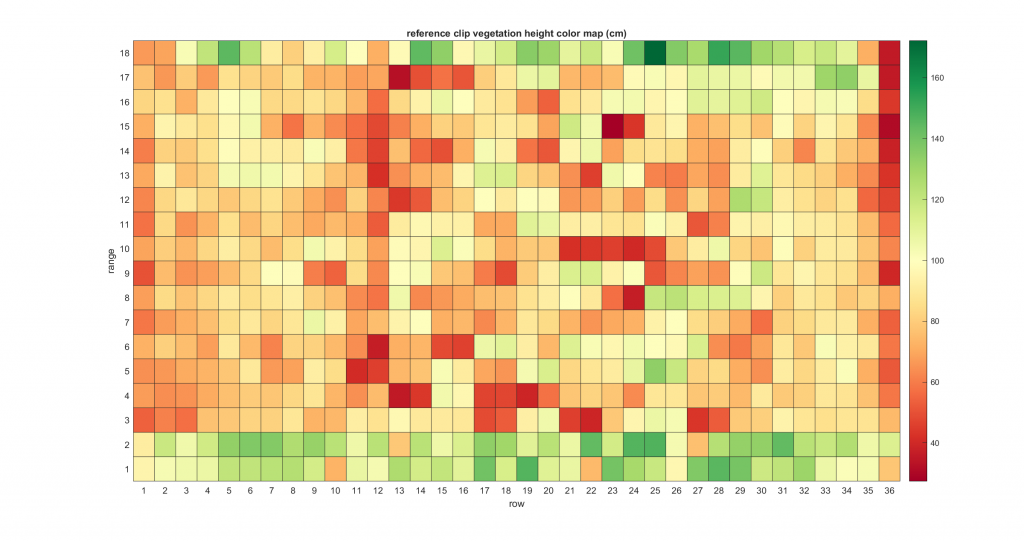

With one foot in education and the other in research, Camarillo has a unique perspective on CIMMYT’s strategy for bringing tools and findings out of the lab, and towards the next step in the impact pathway. A key part of her work involves helping to research physiological traits by developing new tools to increase phenotyping efficiency in the breeding pipeline.

In particular, she is working on a project to develop high-throughput phenotyping tools, which use hyperspectral sensors and cameras to measure several traits in plants. This can help reflect how the plant is responding to different stresses internally, and helps physiologists and breeders understand how the plant behaves within a specific environment, and then quickly integrate these traits into the breeding process.

“Overall it increases the efficiency of selection, so farmers will have better materials, better germplasm, and more reliable yield across environments in a shorter period of time,” says Camarillo.

Sharing the recipe for success

Camarillo’s role in both breeding and training speaks to CIMMYT’s historic and proven strategy of working with national programs to effectively deliver improved seeds to the farmers who need them. In addition to developing friendships with trainees from around the world, she is helping CIMMYT to expand its global network of research and agriculture professionals.

As a product and purveyor of a great agricultural education, Camarillo is dedicated to it passing on. “I think we have to invest in education,” she says. “It is the only path to solve the current problems we face, not only in agriculture, but in every single discipline.”

“If we don’t invest and take the time for education, our future is very uncertain.”