Can we accelerate gender equality?

In an introductory essay for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation 2022 Goalkeepers report, Melinda French Gates explores progress against the UN General Assembly’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Latest analysis by the foundation and its partner Equal Measures 2030 suggests gender equality will not be achieved for 100 years, three generations later than hoped.

French Gates believes initiatives to improve gender equality “treats symptoms, not the cause”, which is why the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) incorporates gender equality work into each project. Social norms and gender-based labor division mean women are often confined to set roles in agricultural production, leading to exclusion from decision-making and a lack of control over their economic wellbeing and household food security. Across CIMMYT’s work in the Global South, researchers are addressing multiple aspects of gender inequality.

Training shows women their power

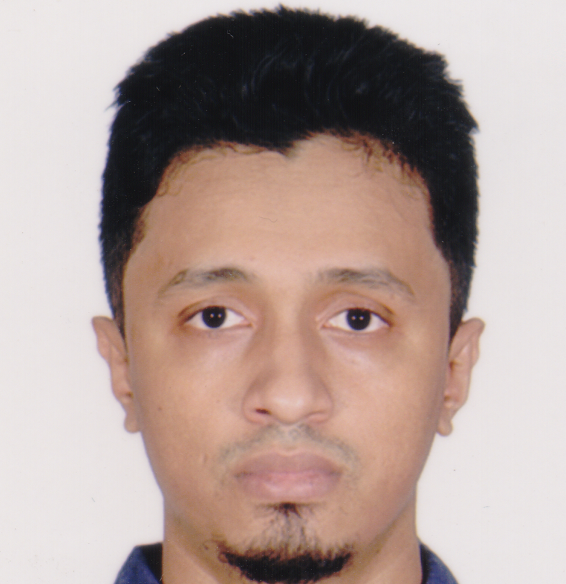

Rina Begum, Nilufar Akter and Monika Rani are Bangladeshi women supported by CIMMYT to achieve their highest economic potential. Developing their business acumen enabled the women to take on essential roles in the workplace, establish themselves in their communities, and fund their children’s education.

CIMMYT-led workshops helped the women grow their self-confidence and identify where their skills and knowledge could enhance their economic situations. In turn, they are keen to help more women access the same opportunities for independence and growth.

“I used to think I wasn’t cut out for light engineering because it was primarily male-dominated, but I was mistaken”, confessed Akter. “This industry has a lot to offer to women, and I’m excited at the prospect of hiring more of them.”

“When women have economic means in their own hands—not just cash, but in an account that they control—it unlocks all kinds of things for their lives,” French Gates says.

Adapting research methods to women’s needs

CIMMYT’s Accelerating Genetic Gains in Maize and Wheat (AGG) project is designing a better framework for faster turnover of improved varieties and increased access for women and marginalized farmers. However, traditional data collection methods may not be suitable for understanding the true experiences of rural women.

Instead, researchers have adapted their data collection methods to cultural restrictions, where women may feel unable to talk openly. Instead of a traditional survey, the team used five vignettes that explore how the production and consumption decisions are held within the households. Respondents then chose the scenario that best represents their own experiences.

Providing opportunities for women to tell their stories in more accessible ways will lead to richer qualitative data, which can improve the development and implementation of gender interventions.

Climate change and gender equality

For International Day of Women and Girls in Science this year, researcher Tripti Agarwal shared her research on the impact of Climate-Smart Agricultural Practices (CSAPs) on women and farming households in Bihar, India. The region is at risk of natural disasters, causing agricultural production loss and food insecurity – with women’s food security more severely affected.

Climate-Smart Villages (CSVs) could offer a solution by acknowledging the gender gap and promoting gender-equitable approaches in enhancing knowledge, developing capacity and improving practices. Through the adoption of climate-resilient practices and technologies, CSV reduces the risk of crop loss and ensures there is enough food for the household.

Agarwal also highlights the work that men must do to level the playing field. “When we talk about women, especially in rural/agricultural contexts, we see that support from the family is critical for them,” said Agarwal. “Creating plans and roadmaps for women would help achieve a gender-empowered agricultural domain, but we must also bring behavior change among men towards a more accepting role of women in farming and decision making.”

Careers for women in science

CIMMYT’s global presence provides opportunities for women to launch and grow their careers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

Madhulika Singh, an agricultural scientist with CIMMYT’s Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA) project, made what was seen as a radical choice to study a STEM subject. She was inspired by seeing other women in her family build successful careers, showing the power of role models in inspiring the next generation. “I grew up thinking ‘there is so much that a woman is capable of,’ whether at home or her workplace,” said Singh.

Initiatives such as CIMMYT’s Women in Crop Science group also help to highlight role models, create mentorship opportunities, and identify areas for change. The group recently received the Inclusive Team award at the inaugural CGIAR Inclusive Workplace Awards.

“When I see women achieving their dreams in science, or as businesswomen, and supporting other women, that keeps me hopeful,” said French Gates.

Read the article: Melinda French Gates on her foundation’s shocking findings that gender equality won’t happen for 100 years: ‘Money is power’

Cover photo: A girl in India harvests good quality hybrid green maize cobs. Women and girls play an essential role in global agriculture. (Credit: CSISA/Wasim Iftikar.)