The democratization of innovation

When the Norwegian Red Cross hired Kristian Wengen and his consulting firm Tinkr to launch a “Scaling for Success” initiative, he found himself at a crossroads. From international aid projects aiming to address the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to private companies seeking to expand their market, everyone was talking about the challenges of scaling up – expanding and sustaining successful programs to reach a greater number of people – but there were few clear paths to solutions.

The Scaling Scan has solutions to offer

But when Wengen came across a project using a tool called the Scaling Scan that identifies and analyzes 10 critical elements for assessing the scalability of any pilot project, he knew he had found a way forward. He was excited, but also worried because the project using the Scaling Scan had concluded.

Concerned he would lose access to the best tool he had found by far, Wengen connected with Lennart Woltering, who created the Scaling Scan for the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) in collaboration with a Dutch-supported project on private-public partnerships called the PPPLab. Woltering and Wengen began a dialogue regarding repurposing the Scaling Scan for Wengen’s context.

“What I like about the Scaling Scan is that it works on a very detailed level to produce systemic results,” said Wengen. “It brings a simple approach to the complex problems of scalability, which allow organizations to achieve efficient solutions, regardless of their geographic or demographic context.”

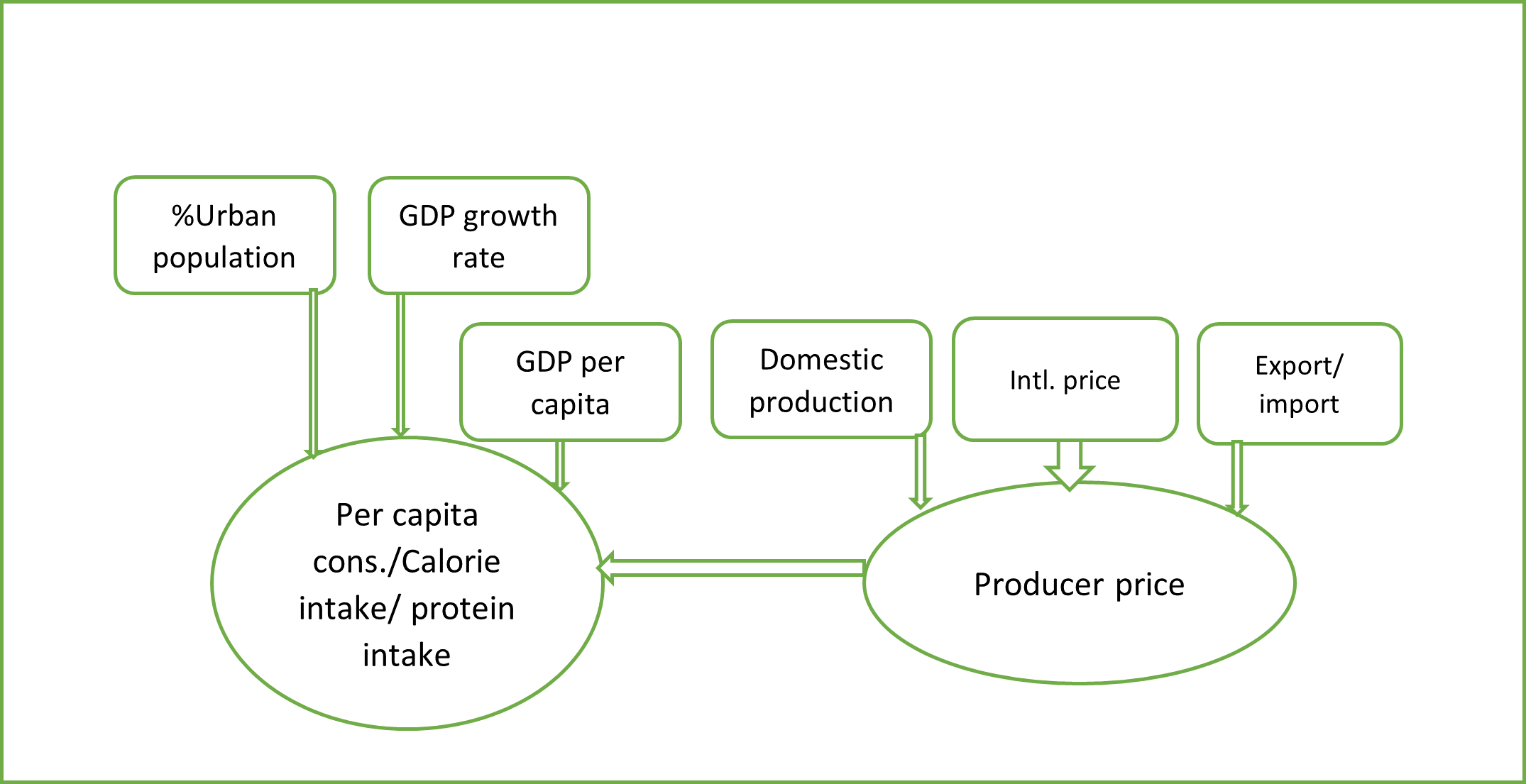

The Scaling Scan focuses attention on discrete components – from finance and business cases to technology and skills – which are necessary to successfully scale an innovation. But it also spurs insight into how each of these necessary ingredients complement each other as a project prepares to successfully transition, reproduce, and expand.

Wengen believes the most effective work of the Scaling Scan happens in team conversations, and it helps deliver clear feedback that can form the basis of discussions that go straight to the heart of the matter. While the challenges of scaling an innovation are complex, the Scaling Scan cuts through the noise and focuses attention on solving the most important problems, whether related to leadership, collaboration, or public sector governance.

Scaling the Scaling Scan

In their conversations, Wengen and Woltering identified opportunities for improving the Scaling Scan. For example, Wengen is building a digitized, web-based version that, like the original Scaling Scan, will be freely available. He calls it a scorecard, a smaller version which capitalizes on the ability of the Scan to promote productive dialogue that moves a project forward. “I am thrilled to help broaden the reach of the Scaling Scan, as making it available for a much wider audience will democratize innovation,” Wengen said.

“Kristian’s adaptations are exactly how I designed the Scaling Scan to work,” said Woltering. “I wanted it to be straightforward enough to be useful across a broad range of business and development applications and flexible enough to be tailored to the specific needs of a particular region, culture, or marketplace.” Seeing how Wengen has utilized the Scaling Scan across a variety of markets has spurred Wennart to develop the Scaling Scan website, where other interested practitioners can download the tool and share their own innovations. “The Scaling Scan truly has utility across the broadest geographies and socioeconomic ranges,” said Wennart.

Wengen is hoping his scaling scorecard will help drive success in a new collaboration he is undertaking with Innovation Norway, a state-owned organization that helps Norwegian businesses grow and export promising products and services. Wengen believes his scorecard will add immense value to a diverse set of projects ranging from business management software helping bakeries reduce waste and increase profits to zero-carbon ocean-going ships and virtual medical training systems.

This kind of transfer and growth shows that even the Scaling Scan itself can be scaled up from the tropics to the Arctic Circle, and Woltering can’t wait to see where the next successful adaptation will spring up.