Events of the past year have underscored the correlation of food supply chains, and weaknesses that need to be addressed. Tackling threats to global food security caused by COVID-19, conflict, and climate change require joint action and long-term commitments, with approaches based on partnerships, collaborative research and information sharing, and involvement from all actors within agrifood systems.

These topics and potential solutions were integral to the 2022 Norman E. Borlaug International Dialogue, hosted between October 18-20, 2022. With a theme of Feeding a Fragile World and overcoming shocks to the global food system, seminars and workshops explored scalable solutions for adaptation and mitigation to limit global warming and meet the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

One event which proposed a solution to these challenges was Agriculture for Peace (Ag4Peace): A Call for Action, which marked the official launch of a platform aiming to support national food and agriculture strategies.

The initiative was founded by seven partners: Norman Borlaug Foundation, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), Cornell University College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) and Texas A&M University.

During the event, two additional collaborators were announced: World Wide Fund for Nature and Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA).

The Ag4Peace concept

Ag4Peace is built on the understanding that without peace there is no food, and without food there is no peace. Conflicts and violence severely disrupt agricultural processes and limit access to food, which in turn forces people to take increasingly perilous actions as they attempt to secure their lives and those of their families. High food prices and hunger cause instability, migration, and civil unrest as people become more desperate.

Using a collaborative approach, partners will design holistic strategies that encompass the multi-faceted nature of agrifood systems and their interconnections with nature, nutrition, and livelihoods. This requires broad-based collaborations, so the Ag4Peace partners welcome other institutions, private sector, and non-governmental organizations that share their aspirations to join them.

Partners are co-constructing the Cross-Sector Collaboration to Advance Resilient Equitable Agrifood Systems (CC-AREAS), the first operational plan for the platform. This is a 10-year proof-of-concept program that applies a holistic, systems approach to achieve resilient agrifood systems and accelerate development of the circular bioeconomy in five low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) that are increasingly exposed to food security risks due to climate change and reliance on imported staple foods.

They will support national efforts to upgrade agrifood systems, adopt regenerative agriculture and climate-smart strategies, expand the circular bioeconomy, and achieve nutrition and food security goals.

In all aspects of the initiative (science, planning, implementation, and evaluation), participation priority will be given to small-scale farmers, women, and socially diverse groups, which will maximize positive outcomes and ensure inclusivity.

Benefits for farmers, communities, value chain participants, consumers, and ecosystems will be demonstrated throughout to encourage adoption and continued use of improved technologies and practices and demonstrate effectiveness.

Partner support for Ag4Peace

After the concept was introduced by Bram Govaerts, Director General of CIMMYT and recipient of the 2014 Norman Borlaug Award for Field Research and Application, a roundtable discussion with a diverse panel of experts began.

Speakers included Manuel Otero, Director General of the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA), Hon. Sharon E. Burke, Global Fellow of Environmental Change and Security Program at the Wilson Center, Per Pinstrup-Anderson, Professor and World Food Prize Laureate, and Alice Ruhweza, Africa Regional Director of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

Moderated by Margaret Bath, Chair of CIMMYT Board of Trustees, the panelists conveyed Ag4Peace’s aims of building productive, sustainable, and resilient agrifood systems, improving livelihoods for small-scale producers and other value chain actors, and deliver nutritious, affordable diets.

“Hunger is part of the picture of conflict,” explained Burke. “These strapped communities are often competing for resources with each other, within their own boundaries, and sometimes food is a weapon in these places, just as destructive as a bomb or a gun. Without food there is no peace, in the near or the long-term.”

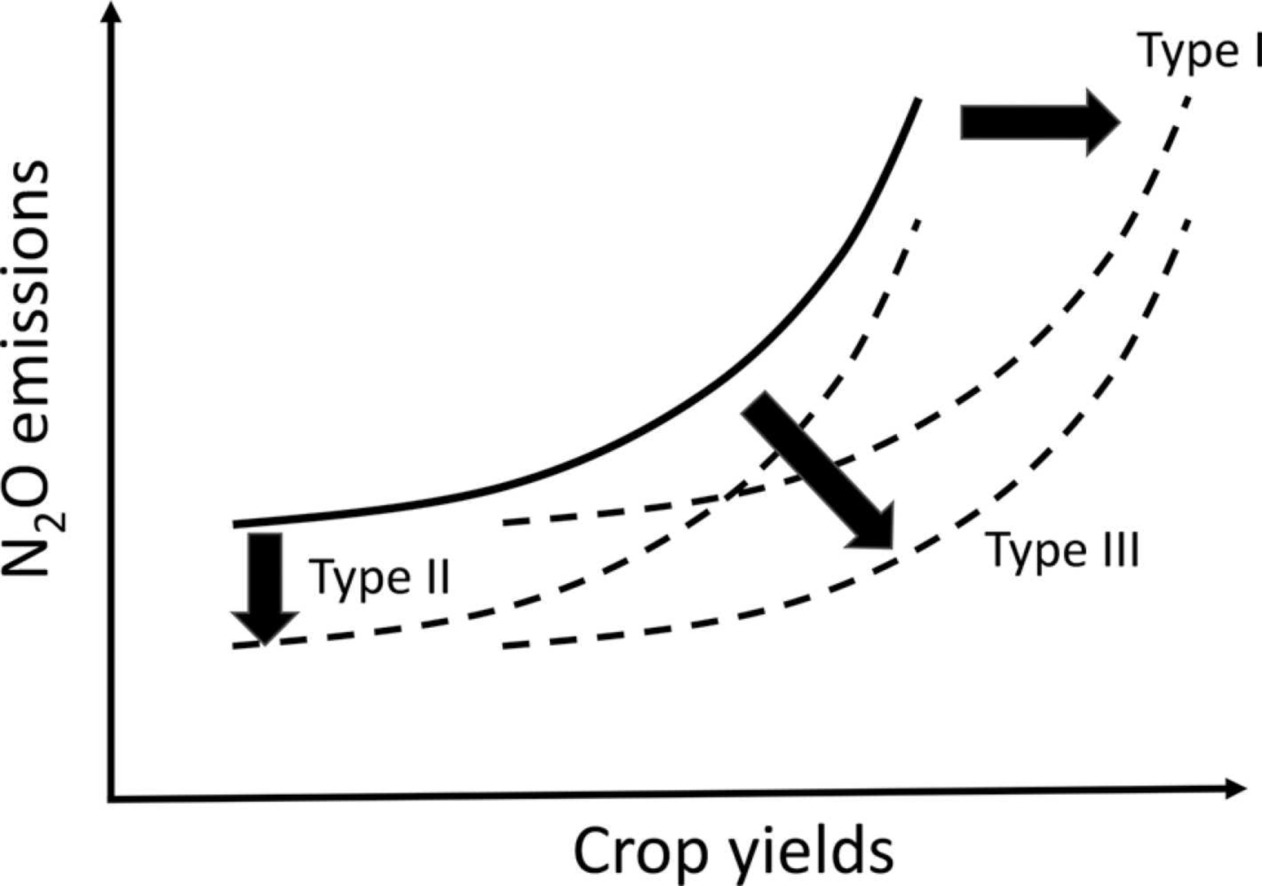

Trade-offs versus win-wins

Pinstrup-Anderson ruminated on the importance of win-wins, which are solutions that work for supporting human health and protecting our natural environment without sacrificing results in one area for results in another. “We do not have to give up improving nutrition just to save the climate or save the earth – we can do both,” he said.

The significance of strong partnerships arose multiple times, such as when Otero explained, “It is not a matter of working just with the agriculture ministers but also with other ministers – foreign affairs, social development, environmental – because agriculture is a sector that crosses across all these institutions.”

Ruhweza explored whether threats to food security, such as COVID-19, conflict, and climate change, can also bring opportunities. “The right action on food systems can also accelerate the delivery of all our goals on climate and nature,” she said. “WWF is looking forward to partnering with this initiative.”

Final remarks from Julie Borlaug, President of the Norman Borlaug Foundation, where the platform will be housed, reiterated a call for more partners to join the coalition. “This is a learning lesson as we go. We will iterate over and over until we get it right, so we need all of you to be involved in that,” said Borlaug. “Join us as we move forward but let us know as we’re going sideways.”

CGIAR scientist honored with award

The winner of the annual Norman Borlaug Award for Field Research and Application award was announced at the Borlaug Dialogue, which this year went to Mahalingam Govindaraj, Senior Scientist for Crop Development at HarvestPlus and at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, a CGIAR research center.

Govindaraj received the award for his leadership in mainstreaming biofortified crops, particularly high-yielding, high-iron, and high-zinc pearl millet varieties. This work has contributed to improved nutrition for thousands of farmers and their communities in India and Africa, and estimates show that, by 2024, more than 9 million people in India will be consuming iron- and zinc-rich pearl, benefiting from improved nutrition.

Cover photo: The historical moment when Manuel Otero, Director General of IICA, joins the Agriculture for Peace initiative with Bram Govaerts, Director General of CIMMYT. (Photo: Liesbet Vannyvel/CIMMYT)