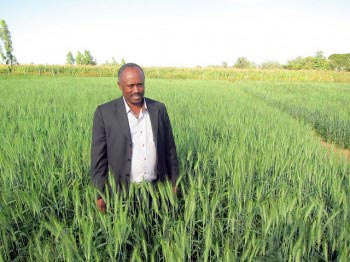

Ethiopia’s seed co-ops benefit entrepreneurs and smallholder farmers

BISHOFTU, Ethiopia (CMMYT) — Farmer and social entrepreneur Amaha Abraham sets his sights high.

The 45-year-old aims to become as wealthy as Saudi Arabian-Ethiopian Mohammed Al Amoudi, who in March 2014 was estimated by Forbes magazine to have a net worth of $15.3 billion.

In an effort to achieve that goal Abraham is backing big reforms in Ethiopia’s agriculture sector.

He is at the forefront of a new grassroots seed marketing and distribution program supported by the Ethiopian Agricultural Transformation Agency (ATA) and the Ministry of Agriculture to improve the country’s wheat crop through the marketing of improved seed by multiple producers and agents.

Under the program, government-subsidized farmer-run cooperatives produce high-yielding, disease-resistant wheat seed, accelerating distribution and helping smallholder farmers grow healthy crops to bolster national food security.

About 50 farmers belong to each cooperative, planting about 100 hectares (250 acres) of government-certified seed, which produce improved wheat varieties they then multiply and sell to smallholder farmers. Seed sales garner a 15 to 20 percent price premium over wheat-grain sales, providing a significant financial incentive.

“I’ve reached so many farmers, so that their land will be covered by proper improved seeds,” Abraham said.

“When I take the seeds to them I give training and advice, which attracts more farmers to get involved. The government visits and organizes training on my land – they recognize my efforts and they’re pushing other farmers to do the same thing.”

STREAMLINED SYSTEMS

The Direct Seed Marketing (DSM) program is part of Ethiopia’s “Wheat Productivity Increase Initiative,” which aims to end the country’s reliance on wheat imports – equal to 1.1 million metric tons (1.2 million tons) or about 24 percent of domestic demand, which is 4.6 million metric tons in 2014, according to the Wheat Atlas, citing statistics from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Previously, the process of getting new wheat seed varieties to farmers was allocation based, with limited producers and agents and a limited choice of varieties, said Sinshaw Alemu, wheat and barley chain program analyst at ATA.

“It was a seed distribution system, not a seed marketing system,” Alemu explained. “DSM is based on the concept that the producers of the seed should be able to market and then sell it at the primary level and farmers will have their choice of seed.”

Farmers can now collect seeds from a certified agent – either a primary cooperative or a private outlet where a direct channel is established with seed producers, leading to timely deliveries and better estimates of potential demand. They can buy government-allocated seed as they did under the other system or the agent can now contact the seed enterprise and purchase additional wheat varieties at a farmer’s request with no fixed allocations in DSM.

“One of the issues in the previous system was that due to delays on demand estimations from woredas (district councils), the unions and primary cooperatives had little or no control over the kind and quality of seed allocated to them,” Alemu said.

“Primary cooperatives had to take it and seed remained unsold at the end of the planting season because either the variety or quality wasn’t what they were looking for – the primary cooperative was left with hundreds of quintals of seed and they had no use for it.”

“We tried the DSM in five woredas in 2014, and it was very successful – 97 percent of the seed delivered was sold and the remainder taken away – we’ve seen some very encouraging results in this area,” he added.

DISEASE THREAT

In recent years, Ethiopia’s wheat crop has been hit hard by stem and yellow rust epidemics, which at their worst can destroy entire crops. Rust infestation can lead to shriveled grain, yield losses and financial troubles for farmers, who must avoid susceptible wheat varieties.

The revamped seed marketing system can help get the new disease-resilient wheat varieties to farmers more efficiently, said David Hodson, a senior scientist based in Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) who manages RustTracker.org, a global wheat rust monitoring system supported by the Borlaug Global Rust Initiative.

Rust Tracker generates surveillance and monitoring information for emerging rust threats. The information provides an early warning system for disease and can help farmers prepare for epidemics, which could otherwise wipe out their crops.

The Rust Tracker is funded by the Durable Rust Resistance in Wheat project, which is managed by Cornell University and supported by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

GENERATING GERMPLASM

CIMMYT, a non-profit research institute which works with partners worldwide to reduce poverty and hunger by increasing the sustainable productivity of maize and wheat cropping systems, plays a key role in providing germplasm to be tested and improved by government-run national agricultural research systems before it is potentially released to farmers.

Additionally, CIMMYT provides smallholder farmer training and skills development on such topics as crop management and agricultural practices. In Ethiopia, these activities, along with seed multiplication and delivery are being supported by a new $5.75 million grant from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

“CIMMYT supports Ethiopia’s agriculture research in a variety of ways including by training researchers, development agents and farmers skills on modern sciences and filling technical gaps by providing field and laboratory equipment, farm machinery, installing irrigation systems, modernizing breeding programs, improving quality of data, providing germplasm and project funds,” said Bekele Abeyo, a CIMMYT senior scientist and wheat breeder based in Addis Ababa.

“The government is now putting an emphasis on agriculture and the situation is far better and improving,” he said. “The structure and extension systems are there to help farmers – Direct Seed Marketing is making it easier to increase the availability of seeds and complements more traditional public seed.”

Adopting improved wheat varieties increases the number of food secure households by 2.7 percent and reduces the number of chronic and transitory food insecure households by 10 and 2 percent respectively, according to CIMMYT scientist Menale Kassie, one of the authors of “Adoption of improved wheat varieties and impacts on household food security in Ethiopia.”

Ethiopia’s wheat-growing area in 2013 was equivalent to 1.6 million hectares (4 million acres), and the country produced 2.45 metric tons of wheat per hectare, according to the country’s Central Statistical Agency.

VENTURE EVOLVES

In 2013, Abraham harvested about 250 quintals (25 metric tons) of the Digalu wheat seed variety near Bishoftu, a town formerly known as Debre Zeyit in the Oromia Region situated at an altitude of 1,900 meters (6,230 feet) 40 kilometers (25 miles) southeast of Addis Ababa.

Abraham is optimistic. He expects he will soon be able to hire many employees, as he plans to expand his agricultural interests to include beekeeping, dairy cattle, poultry and livestock, he said.

“My main aim is not only to earn more money, but also to teach and share with others – that’s what I value most,” he said. “Regardless of money, there are certain people who have a far-sighted view and I want them to be involved. That’s what I value – I’m opening an opportunity for others and envisioning a far-sighted development plan.”

He still has a way to go before he catches up with Al Amoudi, ranked by Forbes as the 61st wealthiest person in the world.

RECOMMENDED READING:

Adoption of improved wheat varieties and impacts on household food security in Ethiopia

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) — Conservation agriculture, which improves the livelihoods of farmers by sustainably boosting productivity, is becoming a vital part of the rural landscape throughout Mexico and Latin America, leading to a major

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) — Conservation agriculture, which improves the livelihoods of farmers by sustainably boosting productivity, is becoming a vital part of the rural landscape throughout Mexico and Latin America, leading to a major