Capturing a clearer picture

A new guidance note shines a brighter light on the role of women in wheat-based farming systems in the Indo-Gangetic Plains and provides actionable recommendations to researchers, rural advisory services, development partners, and policymakers on how to support working communities more effectively and knowledgeably. The publication, Supporting labor and managerial feminization processes in wheat in the Indo-Gangetic Plains: A guidance note, is based on a literature review, including work by researchers at and associated with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and Pandia Consulting.

“Feminization of agriculture is happening in wheat-based systems in South Asia, but these processes are under-researched and their implications are poorly understood. This guidance note, focusing on Bangladesh, India, Nepal and Pakistan, highlights some of the commonalities and differences in feminization processes in each country,” said Hom Gartaula, gender and social inclusion specialist at CIMMYT, and one of the lead authors of the study.

This eight-page publication is based on research funded by the CGIAR Collaborative Platform on Gender Research, the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and the CGIAR Research Program on Wheat (WHEAT).

How great innovations miss critical opportunities by ignoring women

Even the most well-intentioned agricultural interventions can have external costs that can hinder economic development in the long run. The guidance note cites a study that reveals, during India’s Green Revolution, that the introduction of high-yielding varieties of wheat actually “led to a significant decline in women’s paid hired labor because wheat was culturally defined as suited to male laborers. Male wages rose, and women’s wages fell.” Importantly, most women did not find alternative sources of income.

This is not to say that the high-yielding varieties were a poor intervention themselves; these varieties helped India and Pakistan stave off famine and produce record harvests. Rather, the lack of engagement with social norms meant that the economic opportunities from this important innovation excluded women and thus disempowered them.

A closer look at labor feminization and managerial feminization processes

The guidance note points out that it is not possible to generalize across and within countries, as gender norms can vary, and intersectionalities between gender, caste and other identities have a strong impact on women’s participation in fieldwork. Nevertheless, there seem to be some broad trends. The fundamental cross-cutting issue is that women’s contribution to farming is unrecognized, regardless of the reality of their work, by researchers, rural advisory services and policymakers. A second cross-cutting issue is that much research is lodged in cultural norms that reflect gender biases, rather than challenge them, through careful, non-judgemental quantitative and qualitative research.

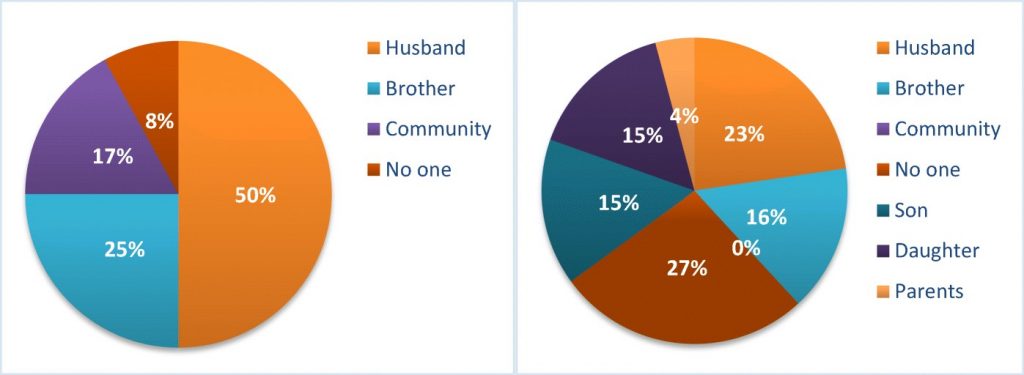

In Bangladesh, women’s participation in agriculture is slowly increasing as off-farm opportunities decline, though it remains limited compared to women in the other countries examined. Hired agricultural work is an important income source for some women. Emerging evidence from work from CSISA and CIMMYT shows that women are becoming decision-makers alongside their husbands in providing mechanization services. Nevertheless, technical, economic and cultural barriers broadly constrain women’s effective participation in decision-making and fieldwork.

In India, agricultural labor is broadly feminizing as men take up off-farm opportunities and women take up more responsibilities on family farms and as hired laborers. Yet information derived from CIMMYT GENNOVATE studies cited in the guidance note shows that external actors, like rural advisory services and researchers, frequently make little effort to include women in wheat information dissemination and training events despite emerging evidence of women taking managerial roles in some communities. Some researchers and most rural advisory services continue to work with outdated and damaging assumptions about “who does the work” and “who decides” that are not necessarily representative of farmers’ realities.

Women in Nepal provide the bulk of the labor force to agriculture. With men migrating to India and the Gulf countries to pursue other opportunities, some women are becoming de-facto heads of households and are making more decisions around farming. Still, women are rarely targeted for trainings in on-farm mechanization and innovation. However, there is evidence that simple gender-equality outreach from NGOs and supportive extension agents can have a big impact on women’s empowerment, including promoting their ability to innovate in wheat.

In Pakistan, male out-migration to cities and West Asia is a driving force in women’s agricultural involvement. Significant regional differences in cultural norms mean that women’s participation and decision-making varies across the country, creating differences regarding the degree to which their increased involvement is empowering. As in the other three countries, rural advisory services primarily focus on men. This weakens women’s ability to make good farming decisions and undermines their voice in intra-household decision-making.

Recommendations

Research should be conducted in interdisciplinary teams and mindsets, which helps design both qualitative and quantitative research free of assumptions and bias. Qualitative and quantitative researchers need to better document the reality of women’s agricultural work, both paid and unpaid.

National agricultural research systems, rural advisory services and development partners are encouraged to work with local partners, including women’s groups and NGOs, to develop gender-transformative approaches with farmers. Services must develop more inclusive criteria for participation in field trials and extension events to invite more women and marginalized communities.

Policymakers are invited to analyze assumptions in existing policies and to develop new policies that better reflect women’s work and support women’s decision-making in the agricultural sector. Researchers should provide policymakers with more appropriate and up-to-date gender data to help them make informed decisions.

These recommendations name a few of many suggestions presented in the guidance note that can ensure agricultural feminization process are positive forces for everyone involved in wheat systems of the Indo-Gangetic Plains. As a whole, acknowledging the reality of these changes well underway in South Asia — and around the world — will not just empower women, but strengthen wheat-based agri-food systems as a whole.

Cover photo: Farmer Bhima Bhandari returns home after field work carrying her 7-month-old son Sudarsan on her back in Bardiya, Nepal. (Photo: Peter Lowe/CIMMYT)