CIMMYT E-News, vol 6 no. 2, February 2009

Demand for maize has popped up across Asia, but much of the grain is enjoyed by poultry, not people. In Bangladesh, maize is a fairly new crop, yet demand in this country already mirrors that of neighboring nations like China and India. A recent CIMMYT report explores these emerging trends and the efforts to incorporate sustainable and economically viable maize cropping systems into a traditionally rice-based country.

Demand for maize has popped up across Asia, but much of the grain is enjoyed by poultry, not people. In Bangladesh, maize is a fairly new crop, yet demand in this country already mirrors that of neighboring nations like China and India. A recent CIMMYT report explores these emerging trends and the efforts to incorporate sustainable and economically viable maize cropping systems into a traditionally rice-based country.

“Simply put, people have more money,” says Olaf Erenstein, a CIMMYT agricultural economist. “Asia’s population growth has slowed and incomes have increased. This means dietary demands and expectations are changing as well.”

With extra money in their pockets, many people across Asia are starting to desire something with a bit more bite. In the past 40 years, increased prosperity and a related meat demand have sent two-thirds of global maize production toward animal feed instead of direct consumption. Currently, 62% of maize in Asia is used to feed livestock while only 22% goes straight to the dinner plate. This is not surprising, as total meat consumption in the seven major Asian maize-producing countries1 rose 280% between 1980 and 2000. Poultry, particularly, plays a large role. During the same time period, poultry production rose 7% each year in Asia, compared to a 5% global average.

The bare-bones reason for this shift is that it takes more grain to produce meat than would be used if people ate the product directly. Grain-to-meat conversion ratios for pork are on the order of 4:1. Chicken is more efficient, requiring only 2 kilograms of grain feed for a kilogram of growth. Either way, when people substitute meat for grain, grain production must increase to meet the demand.

From a farmer’s perspective, this is not a bad thing, and what is occurring now in Bangladesh illustrates how farmers can benefit, according to a recently published CIMMYT study. With a 15%-per-year increase in Bangladesh’s poultry sector since 1991, the feed demand has opened a new market for maize. And since the country’s current average per person poultry consumption is at less than 2 kg a year—compared to almost 4 kg in Pakistan, 14 kg in Thailand, and 33 kg in Malaysia—the maize and poultry industries have plenty of room to spread their wings.

What came first: The chicken or the seed?

The poultry industry in Bangladesh employs five million people, with millions of additional households relying on poultry production for income generation and nutrition. “Only in the past 10 to 15 years, as many people got a bit richer, especially in urban centers, did the market for poultry products, and therefore the profitability of maize, take off in Bangladesh,” says Stephen Waddington, who worked as regional agronomist in the center’s Bangladesh office during 2005-07 and is a co-author of the CIMMYT study.

“Many maize growers keep chickens, feed grain to them, and sell the poultry and eggs; more value is added than by just selling maize grain,” he says. “Most Bangladeshis have no history of using maize as human food, although roasting cobs, popcorn, and mixing maize flour with wheat in chapattis are all increasing.” Waddington adds that maize could grow in dinnertime popularity, as the price of wheat flour has increased and the price of maize grain remains almost 40% lower than that for wheat.

Worldwide, more maize is produced than any other cereal. In Asia, it is third, after rice and wheat. But due to the increasing demand for feed, maize production in Asia has almost quadrupled since 1960, primarily through improved yields, rather than area expansion. Future rapid population growth and maize demand will lead to maize being grown in place of other crops, the intensification of existing maize lands, the commercialization of maize-based production systems, and the expansion of maize cultivation into lands not currently farmed. The International Food Policy Research Institute estimates that Asia will account for 60% of global maize demand by 2020.

Maize in Bangladesh is mainly a high-input crop, grown with hybrid seed, large amounts of fertilizer, and irrigation. While a successful maize crop requires high inputs, it also provides several advantages. “Maize is more than two times as economical in terms of yield per unit of land as wheat or Boro rice,” says Yusuf Ali.”Maize also requires less water than Boro rice and has fewer pest and disease problems than Boro rice or wheat.” The maize area in Bangladesh is increasing around 20% per year.

Maize-rice cropping challenges

“The high potential productivity of maize in Bangladesh has yet to be fully realized,” says Yusuf Ali, a principal scientific officer with the On-Farm Research Division (OFRD) of the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (BARI) and first author of the CIMMYT study. Bangladesh has a subtropical climate and fertile alluvial soils, both ideal for maize. From only a few thousand hectares in the 1980s, by 2007-08 its maize area had expanded to at least 221,000 hectares, he said.

Maize in Bangladesh is cropped during the dry winter season, which lasts from November to April. The other two crops commonly grown during winter are high-yielding irrigated rice (known in Asia as “Boro,” differentiating it from the flooded paddy rice common throughout the region) and wheat. Adding another crop into the mix and thereby increasing cropping diversity is beneficial for farmers, offering them more options.

Rice, the traditional staple cereal crop in Bangladesh, is grown throughout the country year round, often with two to three crops per year on the same land. So as the new crop on the block, maize must be merged with existing cropping patterns, the most common of which is winter maize sown after the harvest of paddy rice. And since rice is the key to food security in Bangladesh, farmers prefer to grow longer-season T. aman rice that provides higher yields than earlier-maturing varieties. This delays the sowing of maize until the second or third week of December. Low temperatures at that time slow maize germination and growth, and can decrease yields more than 20%. In addition, the later-resulting harvest can be hindered by early monsoon rains, which increase ear rot and the threat of waterlogging.

Another problem with maize-rice cropping systems is that the two crops require distinct soil environments. Maize needs loamy soils of good tilth and aeration, whereas rice needs puddled wet clay soils with high water-holding capacity. Puddling for rice obliterates the soil structure, and heavy tillage is required to rebuild the soil for maize. This is often difficult due to a lack of proper equipment, time, or irrigation. Moreover, excessive tillage for maize can deplete soils of nutrients and organic matter. Thus, as maize moves into rice-based cropping systems, agronomists need to develop sustainable cropping patterns, tillage management options, and integrated plant nutrient systems.

Support and supplies vital for success

“For a new crop like hybrid maize to flourish, there needs to be a flow of information and technology to and among farmers,” Waddington says.

In collaboration with the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (BARI), the Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE), and various non-governmental organizations, CIMMYT provided hands-on training for maize production and distributed hybrid seed (which tends to be higher-yielding and more uniform, but must be purchased and planted each year to experience full benefits) to over 11,000 farm families across 35 districts in Bangladesh from 2000-06. A CIMMYT report showed that farmers who received the training were more likely to plant their maize at the best times and also irrigated more frequently and adopted optimal cropping patterns and fertilizer use, resulting in higher yields and better livelihoods.

“This training is vital, since the country is full of tiny, intensively-managed farms. Maize tends to be grown by the somewhat better resourced farmers, but these are still small-scale, even by regional standards,” says Waddingon, adding that farm families were eager to improve their maize-cropping knowledge and their fields.

Other efforts include BARI’s development and release of seven maize hybrids largely based on germplasm from CIMMYT. Two of the hybrids consistently produce comparable grain yields to those of commercial hybrids. The Institute is also working on short duration T. aman rice varieties that have yields and quality comparable to traditional varieties and could thus allow timelier planting of maize.

Power tillers seed the future

Another important advancement is the power-tiller-operated seeder (PTOS) created by the Wheat Research Center (WRC) of BARI. Originally for wheat, the machine has been modified and used to plant maize. Additional PTOSs need to be built, tested, and marketed. Another promising piece of equipment in the works is a power-tiller-operated bed former. Because making and destroying soil beds between every rice/maize rotation is not practical or efficient, the WRC-BARI/CIMMYT farm machinery program is working on a tiller that simultaneously creates a raised bed, sows seed, and fertilizes. This is vital since the turnaround time between rice and maize crops is limited. Like the PTOS, further testing and promotion are needed.

Though much work is still required to incorporate maize fully and sustainably into Bangladesh’s cropping systems, it has already spread across the country quicker than anticipated. Even so, scientists believe future production will fall short of demand. This gap provides farmers an additional crop option, and plants maize in a good position for future growth in Bangladesh.

For more information: Enamul Haque, program manager, CIMMYT-Bangladesh office (e.haque@cgiar.org).

1 China, India, Indonesia, Nepal, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam were identified in a CIMMYT study as Asian countries with more than 100 K hectares sown with maize. At the time of the study, Bangladesh did not meet this maize area requirement and therefore is not included in this statistic.

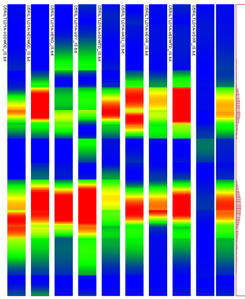

CIMMYT’s wheat quality lab expands and upgrades to meet growing demand of wheat for diverse food uses.

CIMMYT’s wheat quality lab expands and upgrades to meet growing demand of wheat for diverse food uses. A new genomic map that applies to a wide range of maize breeding populations should help scientists develop more drought tolerant maize.

A new genomic map that applies to a wide range of maize breeding populations should help scientists develop more drought tolerant maize.

Sandwiched between China and India, the Kingdom of Bhutan is a small country that relies on maize in a big way. But maize yields are typically low due to crop diseases, drought, and poor access to seed of improved varieties, among other reasons. CIMMYT is committed to improving Bhutan’s food security by providing high-yielding, pest-resistant maize varieties to farmers and capacity-building for local scientists.

Sandwiched between China and India, the Kingdom of Bhutan is a small country that relies on maize in a big way. But maize yields are typically low due to crop diseases, drought, and poor access to seed of improved varieties, among other reasons. CIMMYT is committed to improving Bhutan’s food security by providing high-yielding, pest-resistant maize varieties to farmers and capacity-building for local scientists.

“Our CIMMYT office in Nepal has assisted Bhutan with maize and wheat genetic material, technical backstopping, training, visiting scientist exchange, and in identifying key consultants on research topics such as grey leaf spot and seed production,” says Tiwari.

“Our CIMMYT office in Nepal has assisted Bhutan with maize and wheat genetic material, technical backstopping, training, visiting scientist exchange, and in identifying key consultants on research topics such as grey leaf spot and seed production,” says Tiwari. US Secretary of State Colin Powell paid tribute to Iowa and in particular to one man, known as the father of the Green Revolution, who was born there 90 years ago.

US Secretary of State Colin Powell paid tribute to Iowa and in particular to one man, known as the father of the Green Revolution, who was born there 90 years ago.

Demand for maize has popped up across Asia, but much of the grain is enjoyed by poultry, not people. In Bangladesh, maize is a fairly new crop, yet demand in this country already mirrors that of neighboring nations like China and India. A recent CIMMYT report explores these emerging trends and the efforts to incorporate sustainable and economically viable maize cropping systems into a traditionally rice-based country.

Demand for maize has popped up across Asia, but much of the grain is enjoyed by poultry, not people. In Bangladesh, maize is a fairly new crop, yet demand in this country already mirrors that of neighboring nations like China and India. A recent CIMMYT report explores these emerging trends and the efforts to incorporate sustainable and economically viable maize cropping systems into a traditionally rice-based country.

Work by CIMMYT with researchers, extension workers, policymakers, and farmers in Bangladesh for nearly four decades has helped establish wheat and maize among the country’s major cereal crops, made farming systems more productive and sustainable, improved food security and livelihoods, and won ringing praise from national decision makers in agriculture, according to a recent report published by CIMMYT.

Work by CIMMYT with researchers, extension workers, policymakers, and farmers in Bangladesh for nearly four decades has helped establish wheat and maize among the country’s major cereal crops, made farming systems more productive and sustainable, improved food security and livelihoods, and won ringing praise from national decision makers in agriculture, according to a recent report published by CIMMYT.

At the Thai Department of Agriculture’s Nakhon Sawan Field Crops Research Center, Pichet Grudloyma, senior maize breeder, shows off the drought screening facilities. Screening is carried out in the dry season, so that water availability can be carefully controlled in two comparison plots: one well-watered and one “drought” plot, where watering is stopped for two weeks before and two weeks after flowering. Many of the experimental lines and varieties being tested this year are here as the result of the Asian Maize Network (AMNET). Funded by the

At the Thai Department of Agriculture’s Nakhon Sawan Field Crops Research Center, Pichet Grudloyma, senior maize breeder, shows off the drought screening facilities. Screening is carried out in the dry season, so that water availability can be carefully controlled in two comparison plots: one well-watered and one “drought” plot, where watering is stopped for two weeks before and two weeks after flowering. Many of the experimental lines and varieties being tested this year are here as the result of the Asian Maize Network (AMNET). Funded by the  For Grudloyma, this collaborative approach is a big change. “We’ve learned a lot and gained a lot from our friends in different countries. We each have different experiences, and when we share problems we can adapt knowledge from others to our own situations.”

For Grudloyma, this collaborative approach is a big change. “We’ve learned a lot and gained a lot from our friends in different countries. We each have different experiences, and when we share problems we can adapt knowledge from others to our own situations.” CIMMYT-led international efforts to identify and deploy sources of resistance to the virulent Ug99 strain of stem rust have received coverage on ABC1, the primary television channel of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

CIMMYT-led international efforts to identify and deploy sources of resistance to the virulent Ug99 strain of stem rust have received coverage on ABC1, the primary television channel of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Three high-quality wheat varieties developed by researchers from the Shandong Academy of Agricultural Science and the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science (CAAS), drawing on CIMMYT wheat lines and technical support, were sown on more than 8 million hectares during 2002-2006, according to a recent CAAS economic study. They contributed an additional 2.4 million tons of grain—worth USD 513 million, with quality premiums.

Three high-quality wheat varieties developed by researchers from the Shandong Academy of Agricultural Science and the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science (CAAS), drawing on CIMMYT wheat lines and technical support, were sown on more than 8 million hectares during 2002-2006, according to a recent CAAS economic study. They contributed an additional 2.4 million tons of grain—worth USD 513 million, with quality premiums.