Cross-regional efforts produce a toolbar for direct seeding of maize

Cheap, light, versatile… and locally manufactured

Direct seeding of maize using a two-wheel tractor has been made possible over the past decade or so by manufacturing companies in China, India, and Brazil (among others) that produce commercially available seeders. Several of these seeders have been tested for the past two or three years in Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Ethiopia under the Farm Mechanization and Conservation Agriculture for Sustainable Intensification (FACASI) project supported by the Australian International Food Security Research Center (AIFSRC).

One of the best performing commercially available seeders (in terms of field capacity, precision in seed rate and planting depth, crop emergence, etc.) is manufactured by the Brazilian company Fitarelli. However, this seeder is expensive (above US$ 4,000), difficult to maneuver (especially in small fields), and lacks versatility (minimum row spacing is 80 cm).

In response, several initiatives have aimed at producing toolbar-based seeders to be manufactured locally and cheaply, that could be used in different configurations (to seed one, two, or more rows) and could perform other operations (such as forming planting beds). One such toolbar is the Gongli seeder, which is well suited to sow small grain crops such as wheat and rice in Asian fields, but not maize under typical field conditions in Africa. Two years ago, Jeff Esdaile, inventor of the original Gongli, and Joseph Mutua, from the Kenya Network for Dissemination of Agricultural Technologies, produced a modified version of the Gongli – the Gongli Africa + thanks to funding from CRP MAIZE (as reported in Informa No. 1862). In parallel, another toolbar using a different design was produced by Jelle Van Loon and his Smart Mechanization/Machinery and Equipment Innovation team at CIMMYT-Mexico.

Both the Gongli Africa + and the Mexican toolbar have their strengths and their weaknesses. Both have also been judged as too heavy by local service providers. Thus, CRP MAIZE and the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture co-funded a two-week session (8-27 October) in Zimbabwe to develop a “hybrid toolbar” having the strengths of both the Gongli Africa + and the Mexican toolbar but weighing under 100 kg. Jeff Esdaile, Joseph Mutua, and Jelle Van Loon spent the entire two weeks manufacturing three prototypes of the hybrid at the University of Zimbabwe. The two-week session also served as hands-on training for staff of three of Zimbabwe’s major manufacturing companies of agricultural equipment (Zimplow LTD, Bain LTD, and Grownet LTD) as well as representatives of the informal sector.

The hybrid toolbar is expected to sell for a quarter of the price of a Fitarelli seeder, although its performance (in terms in term of field capacity, fuel consumption, precision, and crop emergence) is expected to be equivalent. Its weight suits the needs of local service providers better and it is infinitely more versatile (several configurations are possible depending on the desired row spacing, soil conditions, the amount of mulch, etc.). The hybrid toolbar will be thoroughly tested in Zimbabwe during the coming months. A prototype will be shipped to Bangladesh and another to Mexico for further testing and to share the design.

A Fitarelli seeder is good at establishing a maize crop under no-till conditions, but expensive, difficult to operate in small fields, and heavy. Photo: Frédéric Baudron

The first hybrid toolbar being tested at CIMMYT-Harare. It is cheap, easy to maneuver, light, and versatile. Three local companies and informal sector representatives have been trained to manufacture it locally. Photo: Frédéric Baudron

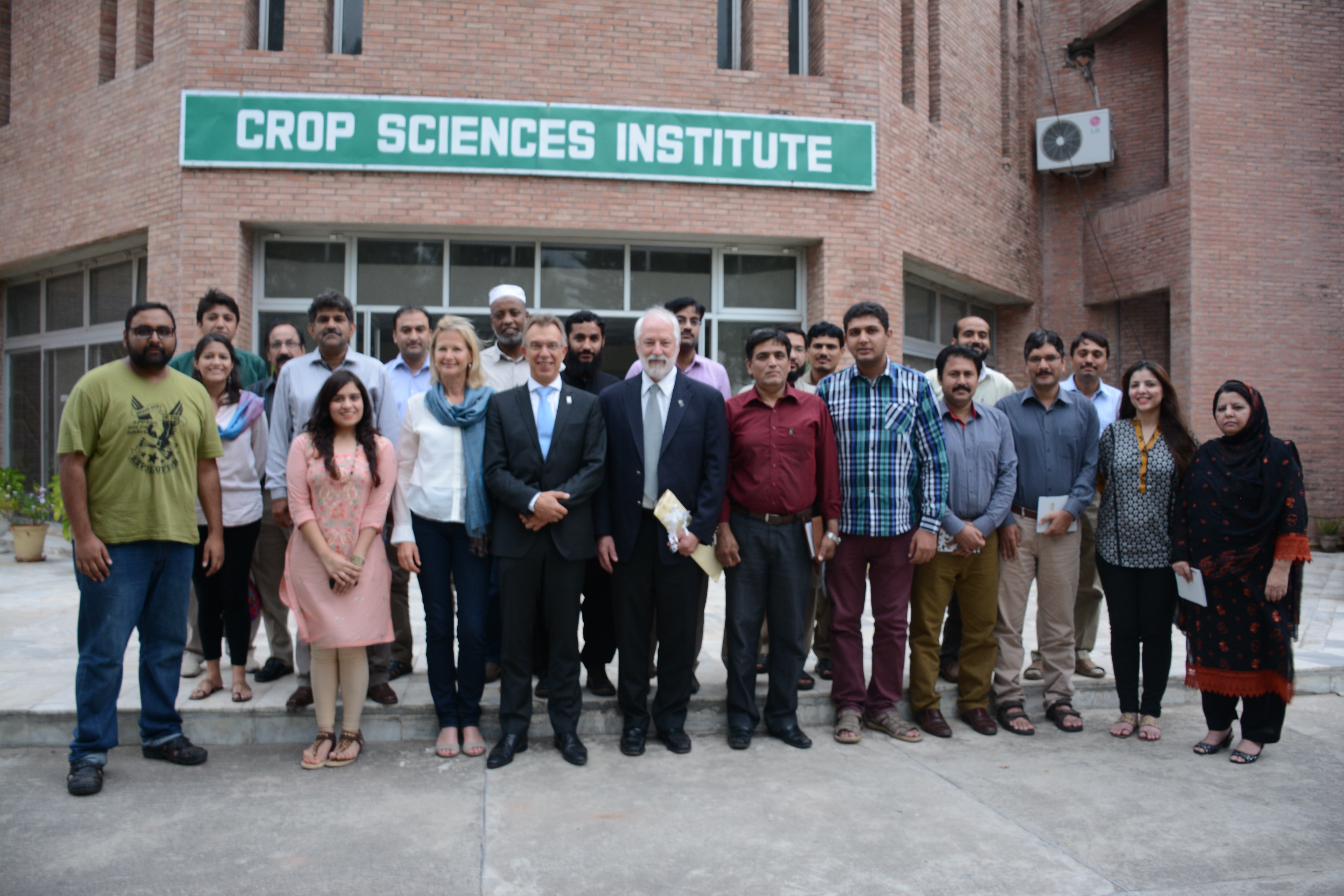

WPEPs Annual Planning Meeting-3The Wheat Productivity Enhancement Program (WPEP), funded by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), held its annual wheat planning meeting organized by Pakistan Agricultural Research Council (PARC) and CIMMYT on 8-10 September 2015 in Islamabad.

WPEPs Annual Planning Meeting-3The Wheat Productivity Enhancement Program (WPEP), funded by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), held its annual wheat planning meeting organized by Pakistan Agricultural Research Council (PARC) and CIMMYT on 8-10 September 2015 in Islamabad.

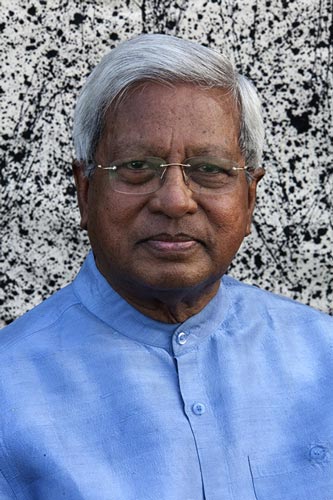

Martin Kropff, CIMMYT Director General, emphasized CIMMYT’s achievements and new ways forward during a talk commemorating his first 100 days as DG, at CIMMYT headquarters in El Batбn, Mexico, on 20 October 2015.

Martin Kropff, CIMMYT Director General, emphasized CIMMYT’s achievements and new ways forward during a talk commemorating his first 100 days as DG, at CIMMYT headquarters in El Batбn, Mexico, on 20 October 2015.