National maize stem borer mass rearing laboratory inaugurated in Pakistan

Islamabad (CIMMYT) — CIMMYT, in partnership with the Pakistan Agricultural Research Council (PARC), inaugurated the first national maize stem borer (Chilo partellus) mass rearing laboratory at the National Agricultural Research Center in Islamabad on 25 October 2016.

Maize stem borer (Chilo partellus) is a destructive insect pest of maize in Pakistan. Yield losses because of this pest are estimated to reach 10-40% and in some severe incidences up to 60% losses have been reported. Application of insecticides is one of the practices mostly used by resource-rich farmers. However, cash-trapped small scale farmers have to face the yield losses unless they apply cultural practices which vary from place to place. The other alternative, perhaps the better option, is the use of tolerant varieties. Maize germplasms that have inherent resistance/tolerance to maize stem borer not only save farmers money from the lower use of pesticides, but also help to have a greener agriculture by reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Identification of host-plant resistance in maize is part of the commissioned projects under the Agricultural Innovation Program (AIP) for Pakistan. Under AIP, stem borer resistance maize varieties sourced from the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) are being screened to identify the varieties best adapted to Pakistan’s maize growing ecology.

To accelerate this screening process, it was necessary to have a stem borer mass rearing facility where larvae could be produced in mass and thereafter released in maize varieties as a form of artificial infestation. “Until recently, it was not possible to conduct such activities in Pakistan due to the non-availability of such a facility. Thanks to the collaboration of PARC and CIMMYT and the generous support from USAID, we are now officially opening the first stem borer mass rearing laboratory in Pakistan,” said M. Imtiaz, CIMMYT’s Country Representative and AIP Project Leader, during his inaugural speech.

Nadeem Amjad, acting Chairman of PARC, said: “During the last couple of years, we have seen very promising results under the AIP maize program. The introduction of high yielding climate resilient maize germplasm, the distribution of protein enriched maize seeds to farmers, testing of pro-vitamin A and zinc enriched maize hybrids and the introduction of biotic stress tolerant maize varieties are among the unique interventions which were not well addressed by Pakistan’s maize sector for long.” During his concluding remarks, Amjad also added that the inauguration of the laboratory will further cement PARC’s decade’s long collaborations with CIMMYT. He thanked CIMMYT and USAID for their generous support.

The field screening under artificial infestation is showing encouraging results where some entries show more than 90% survival rate by resisting the pest attack. “We need to document the results and further check in upcoming seasons to confirm these preliminary results so that tolerant germplasm can be available to end users in the shortest time possible,” says AbduRahman Beshir, CIMMYT’s Maize Improvement and Seed Systems Specialist. The inauguration ceremony was attended by scientists and stakeholders from the public and private sector and USAID. During the inauguration, it was announced that the national laboratory will serve as a training and research center for students and researchers from the public and private sector of Pakistan.

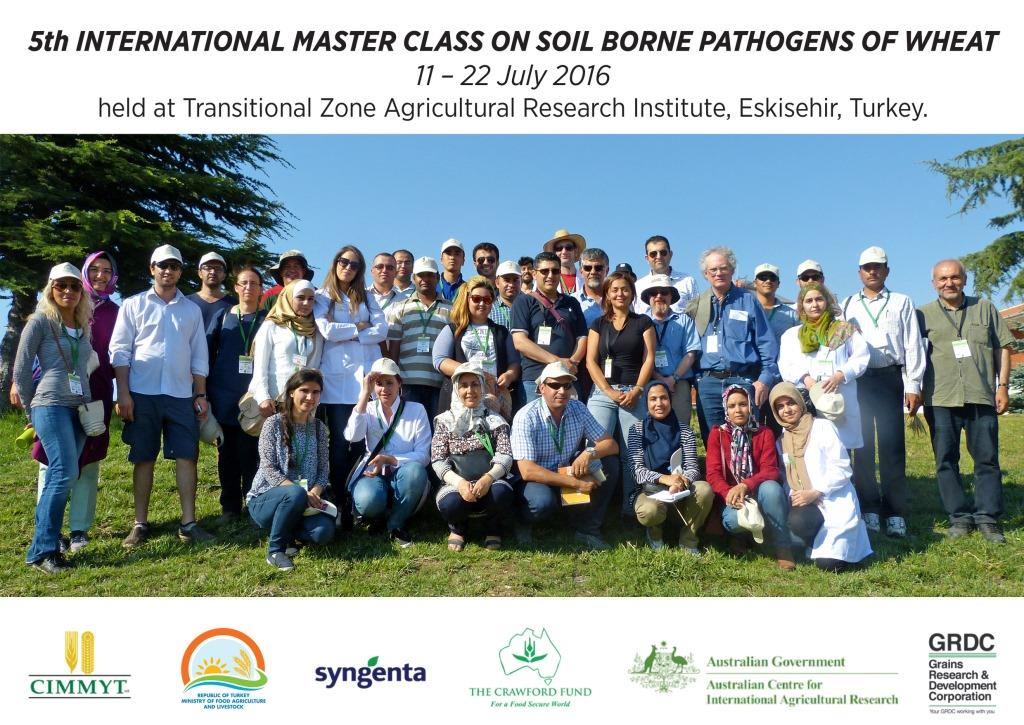

ESKISEHIR, Turkey — The 5th International Master Class on Soil Borne Pathogens of Wheat held at the Transitional Zone Agricultural Research Institute (TZARI), Eskisehir, Turkey, on 11-23 July 2016, brought together 45 participants from 16 countries of Central and West Asia and North Africa.

ESKISEHIR, Turkey — The 5th International Master Class on Soil Borne Pathogens of Wheat held at the Transitional Zone Agricultural Research Institute (TZARI), Eskisehir, Turkey, on 11-23 July 2016, brought together 45 participants from 16 countries of Central and West Asia and North Africa.