Q&A: Expanding CIMMYT’s research agenda on markets and business

TEXCOCO, Mexico (CIMMYT) — Food security is heavily dependent on seed security. Sustainable seed systems ensure that a variety of quality seeds are available to farming communities at affordable prices. In many developing countries, however, farmers still lack access to the right seeds at the right time.

In the past, governments played a major role in getting improved seed to poor farmers. These days, however, the private sector plays a leading role, often with strong support from governments and NGOs.

“Interventions in formal seed systems in maize have tended to focus on improving the capacity of seed producing companies, which are often locally owned small-scale operations, to produce and distribute quality germplasm,” says Jason Donovan, Senior Economist at International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT). “These local seed companies are expected to maintain, reproduce and sell seed to underserved farmers. That’s a pretty tall order, especially because private seed businesses themselves are a fairly new thing in many countries.”

Prior to the early 2000s, Donovan explains, many seed businesses were partially or wholly state-owned. In Mexico, for example, the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) produced seed and supplied it to a market-oriented entity which was responsible for distribution. “What we’re seeing now is locally owned private seed businesses carving out their space in the maize seed market, sometimes in direct competition with multinational seed companies,” he says. In Mexico, around 80 locally owned maize seed producing businesses currently exist, most of which have been involved in CIMMYT’s MasAgro Maize project. These are mostly small businesses selling between 150,000 and 500,000 kg of hybrid maize per year.

In the following Q&A, Donovan discusses new directions in research on value chains, the challenges facing private seed companies, and how new studies could help understand their capacities and needs.

How does research on markets and value chains contribute to CIMMYT’s mission?

We’re interested in the people, businesses and organizations that influence improved maize and wheat seed adoption, production, and the availability and quality of maize and wheat-based foods. This focus perfectly complements the efforts of those in CIMMYT and elsewhere working to improve seed quality and increase maize and wheat productivity in the developing world.

We are also interested in the nutrition and diets of urban and rural consumers. Much of the work around improved diets has centered on understanding fruit and vegetable consumption and options to stimulate greater consumption of these foods. While there are good reasons to include those food groups, the reality is that those aren’t the segments of the food market that are immediately available to or able to feed the masses. Processed maize and wheat, however, are rapidly growing in popularity in both rural and urban areas because that’s what people want and need to eat first. So the question becomes, how can governments, NGOs and others promote the consumption of healthier processed wheat and maize products in places where incomes are growing and tastes are changing?

This year, CIMMYT started a new area of research in collaboration with A4NH, looking at the availability of processed maize and wheat products in Mexico City — one of the world’s largest cities. We’re working in collaboration with researchers form the National Institute of Public Health to find out what types of wheat- and maize-based products the food industry is selling, to whom, and at what cost. At the end of the day, we want to better understand the variation in access to healthier wheat- and maize-based foods across differences in purchasing power. Part of that involves looking at what processed products are available in different neighborhoods and thinking about the dietary implications of that.

Your team has also recently started looking at formal seed systems in various locations. What direction is the research taking so far?

Our team’s current priority is to advance learning around the private sector’s role in scaling improved maize varieties. We are engaged with three large projects: MasAgro Maize in Mexico, Stress Tolerant Maize for Africa (STMA) and the Nepal Seed and Fertilizer Project (NSFP). We are looking to shed light on the productive and marketing capacities of the privately owned seed producing businesses and their ability to get more seed to more farmers at a lower cost. This implies a better understanding of options to better link seed demand and supply, and the business models that link seed companies with agro-dealers, seed producing farmers, and seed consumers.

We are also looking at the role of agro-dealers — shops that sell agricultural inputs and services (including seed) to farmers — in scaling improved maize seed.

At the end of the day, we want to provide evidence-based recommendations for future interventions in seed sectors that achieve even more impact with fewer resources.

This research is still in its initial stages, but do you already have an idea of what some of the key limiting factors are?

I think one of the main challenges facing small-scale seed producing businesses is the considerable expense entailed in simultaneously building their productive capacities and their market share. Many businesses simply don’t have a lot of capital. There’s also a lack of access to specialized business support.

In Mexico, for example, a lot of people in the industry are actually ex-breeders from government agencies, so they’re very familiar with the seed production process, but less so with options for building viable businesses and growing markets for new varieties of seed.

This is a critical issue if we expect locally owned seed businesses to be the primary vehicle by which improved seeds are delivered to farmers at scale. We’re currently in the assessment phase, examining what the challenges and capacities are, and hopefully this information will feed into new approaches to designing our interventions.

Is the study being replicated in other regions as well?

Yes, in East Africa, under the Stress Tolerant Maize for Africa (STMA) project. We’re working with seed producing businesses and agro-dealers in Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda to understand their strategies, capacities, and needs in terms of providing improved seed to more farmers. We’re using the same basic research design in Mexico, and there is also ongoing work in the Nepal Seed and Fertilizer Project. Given that we are a fairly small team within CIMMYT, comparable cross-regional research is one way to punch above our weight.

Why is this research timely or important?

The research is critical as CIMMYT’s impact relies, in part, on partnerships. In the case of improved maize seed, that revolves around viable seed businesses.

Although critical, no one else is actually engaged in this type of seed sector research. There have been a number of studies on seed production, seed systems and the adoption of improved seed by poor farmers. A few have focused on the emergence of the private sector in formal seed systems and the implications for seed systems development, but most have been pretty broad, examining the overall business environment in which these companies operate but not much beyond that. We’re trying to deepen the discussion. While we don’t expect to have all the answers at the end of this study, we hope we can shift the conversation about options for better support to seed companies and agro-dealers.

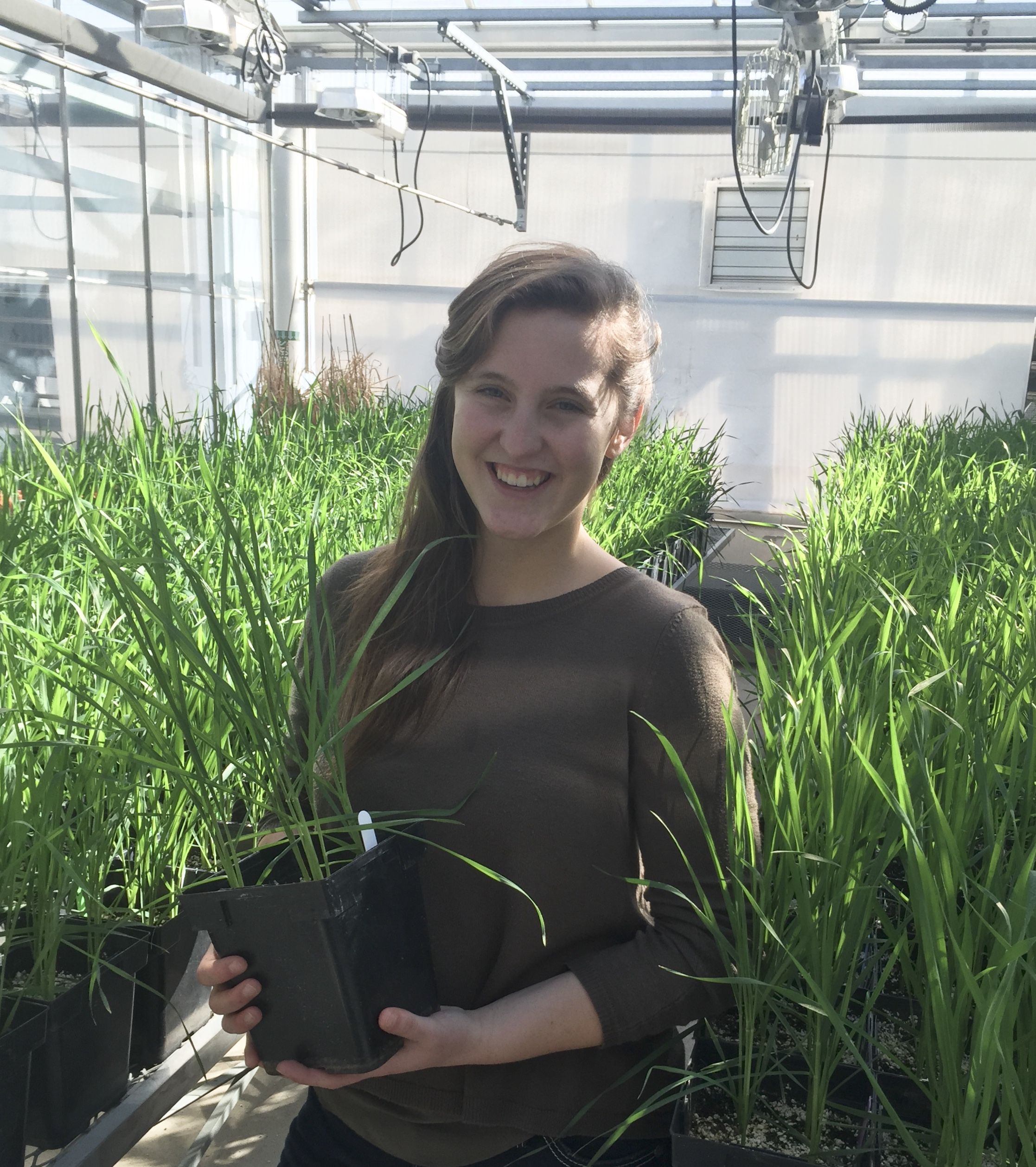

Jason Donovan joined CIMMYT in 2017 and leads CIMMYT’s research team on markets and value chains, based in Mexico. He has some 15 years of experience working and living in Latin America. Prior to joining CIMMYT he worked at the Peru office of the World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF), where his research focused on business development, rural livelihoods, gender equity and certification. He has a PhD in development economics from the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS).