“Better, faster, equitable, sustainable” – wheat research community partners join to kick off new breeding project

More than 100 scientists, crop breeders, researchers, and representatives from funding and national government agencies gathered virtually to initiate the wheat component of a groundbreaking and ambitious collaborative new crop breeding project led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

The new project, Accelerating Genetic Gains in Maize and Wheat for Improved Livelihoods, or AGG, brings together partners in the global science community and in national agricultural research and extension systems to accelerate the development of higher-yielding varieties of maize and wheat — two of the world’s most important staple crops.

Funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the U.K. Department for International Development (DFID), the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research (FFAR), the project specifically focuses on supporting smallholder farmers in low- and middle-income countries. The international team uses innovative methods — such as rapid cycling and molecular breeding approaches — that improve breeding efficiency and precision to produce varieties that are climate-resilient, pest and disease resistant and highly nutritious, targeted to farmers’ specific needs.

The wheat component of AGG builds on breeding and variety adoption work that has its roots with Norman Borlaug’s Nobel Prize winning work developing high yielding and disease resistance dwarf wheat more than 50 years ago. Most recently, AGG builds on Delivering Genetic Gain in Wheat (DGGW), a 4-year project led by Cornell University, which ends this year.

“AGG challenges us to build on this foundation and make it better, faster, equitable and sustainable,” said CIMMYT Interim Deputy Director for Research Kevin Pixley.

At the virtual gathering on July 17, donors and partner representatives from target countries in South Asia joined CIMMYT scientists to describe both the technical objectives of the project and its overall significance.

“This program is probably the world’s single most impactful plant breeding program. Its products are used throughout the world on many millions of hectares,” said Gary Atlin from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. “The AGG project moves this work even farther, with an emphasis on constant technological improvement and an explicit focus on improved capacity and poverty alleviation.”

Alan Tollervey from DFID spoke about the significance of the project in demonstrating the relevance and impact of wheat research.

“The AGG project helps build a case for funding wheat research based on wheat’s future,” he said.

Nora Lapitan from the USAID Bureau for Resilience and Food Security listed the high expectations AGG brings: increased genetic gains, variety replacement, optimal breeding approaches, and strong collaboration with national agricultural research systems in partner countries.

Reconnecting with trusted partners

The virtual meeting allowed agricultural scientists and wheat breeding experts from AGG target countries in South Asia, many of whom have been working collaboratively with CIMMYT for years, to reconnect and learn how the AGG project both challenges them to a new level of collaboration and supports their national wheat production ambitions.

“With wheat blast and wheat rust problems evolving in Bangladesh, we welcome the partnership with international partners, especially CIMMYT and the funders to help us overcome these challenges,” said Director General of the Bangladesh Wheat and Maize Research Institute Md. Israil Hossain.

Director of the Indian Institute for Wheat and Barley Research Gyanendra P. Singh praised CIMMYT’s role in developing better wheat varieties for farmers in India.

“Most of the recent varieties which have been developed and released by India are recommended for cultivation on over 20 million hectares. They are not only stress tolerant and high yielding but also fortified with nutritional qualities. I appreciate CIMMYT’s support on this,” he said.

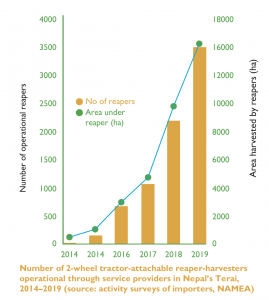

Executive Director of the National Agricultural Research Council of Nepal Deepak K. Bhandari said he was impressed with the variety of activities of the project, which would be integral to the development of Nepal’s wheat program.

“Nepal envisions increased wheat productivity from 2.84 to 3.5 tons per hectare within five years. I hope this project will help us to achieve this goal. Fast tracking the replacement of seed to more recent varieties will certainly improve productivity and resilience of the wheat sector,” he said.

The National Wheat Coordinator at the National Agricultural Research Center of Pakistan, Atiq Ur-Rehman, told attendees that his government had recently launched a “mega project” to reduce poverty and hunger and to respond to climate change through sustainable intensification. He noted that the support of AGG would help the country increase its capacity in “vertical production” of wheat through speed breeding. “AGG will help us save 3 to 4 years” in breeding time,” he said.

For CIMMYT Global Wheat Program Director Hans Braun, the gathering was personal as well as professional.

“I have met many of you over the last decades,” he told attendees, mentioning his first CIMMYT trip to see wheat programs in India in 1985. “Together we have achieved a lot — wheat self-sufficiency for South Asia has been secured now for 50 years. This would not be possible without your close collaboration, your trust and your willingness to share germplasm and information, and I hope this will stay. “

Braun pointed out that in this project, many national partners will gain the tools and capacity to implement their own state of the art breeding strategies such as genomic selection.

“We are at the beginning of a new era in breeding,” Braun noted. “We are also initiating a new era of collaboration.”

The wheat component of AGG serves more than 30 million wheat farming households in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, India, Kenya, Nepal and Pakistan. A separate inception meeting for stakeholders in sub-Saharan Africa is planned for next month.