Slow-release nitrogen fertilizers measure up

Maize, rice and wheat are the major staple crops in Nepal, but they are produced using a lot of fertilizer, which may become an environmental hazard if not completely used up in production. Unfortunately, most farmers apply fertilizers in an unbalanced way.

Urea is a common fertilizer used as a nitrogen source by Nepali farmers. If the time of application is not synchronized with crop uptake, the chances of losses through volatilization releasing ammonia and leaching are high, thereby creating environmental hazards in the atmosphere and downstream.

Through the Nepal Seed and Fertilizer (NSAF) project, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is testing the application of environmentally friendly slow-release nitrogen fertilizer in maize production.

In particular, CIMMYT researchers examined the nutrient-use efficiency of briquetted urea and polymer-coated urea, also known as PCU.

Using regular urea, the efficiency of nitrogen use in maize is limited to 17 kg of grain per kg of nitrogen. Using briquetted urea and polymer-coated urea, efficiency increased to 24 and 28 kg of grain per kg of nitrogen respectively. A higher efficiency also suggests a reduction in losses to the environment.

Overall, results show that briquetted urea and polymer-coated urea can allow reduced nitrogen inputs by as much as 30-40% while maintaining the same yield levels achieved using current government fertilizer recommendations.

Similar to the maize trials, the application of slow-release nitrogen at a lower amount than the recommended rate in wheat showed similar agronomic results to the application of traditional urea at higher rates. Reduced losses allowed 40-50% less nitrogen fertilizer application but maintained the same yield levels as the current recommendation.

Although the cost of polymer-coated urea is comparatively expensive in the market unless subsidized, farmers applying briquetted urea save money and labor and can obtain 54% more profits.

“Briquetted urea is easy to use compared with traditional urea application, since its one-time application method saves labor. Moreover the yield performance is better,” said Devi Sara Thapa, a farmer from Surkhet district.

Climate change is affecting the yield of crops due to increased exposure to higher temperature, water stress and delayed or reduced monsoons, all impacting farmers’ incomes. The NSAF project promotes early maturing crop varieties that are resilient to such climatic stresses and can yield a positive harvest. The project works with seed companies and Nepal’s Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Development to deploy stress resilient maize and rice varieties packaged with cost efficient and effective soil fertility management practices in the project areas.

Researchers are testing and promoting early and extra early maturing open-pollinated varieties that have tolerance to drought or water stress conditions. These varieties are found to yield up to 7.5 tons per hectare and are ready for harvest in less than 100 days. This allows farmers, particularly in the hills and mid hills, to have another crop in the growing season. Such varieties will enhance farmers’ productivity and ensure food security at times of stressful environmental conditions.

CIMMYT is sharing the benefits of adopting these technologies to farmers, cooperatives and ago-dealers, through field demonstrations and farmer field days.

Project staff and partners use seeds and fertilizers that are approved by the Government of Nepal and the United States Agency for International Development’s environmental regulations on pesticide use or support. The team is promoting seed varieties appropriate for specific agroecological conditions and applying best practices on the use and application of fertilizers and integrated soil fertility management.

The Nepal Seed and Fertilizer (NSAF) project, implemented by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), aims to increase the availability of agriculture technologies to improve productivity in select value chains, including maize, rice, lentils, and high-value vegetables. Through the NSAF project, CIMMYT and its partners work to improve the capacity of the public and private sectors in their respective roles: to strengthen and develop commercial seed and fertilizer value chains and to develop markets systems to disseminate agricultural technologies throughout Nepal.

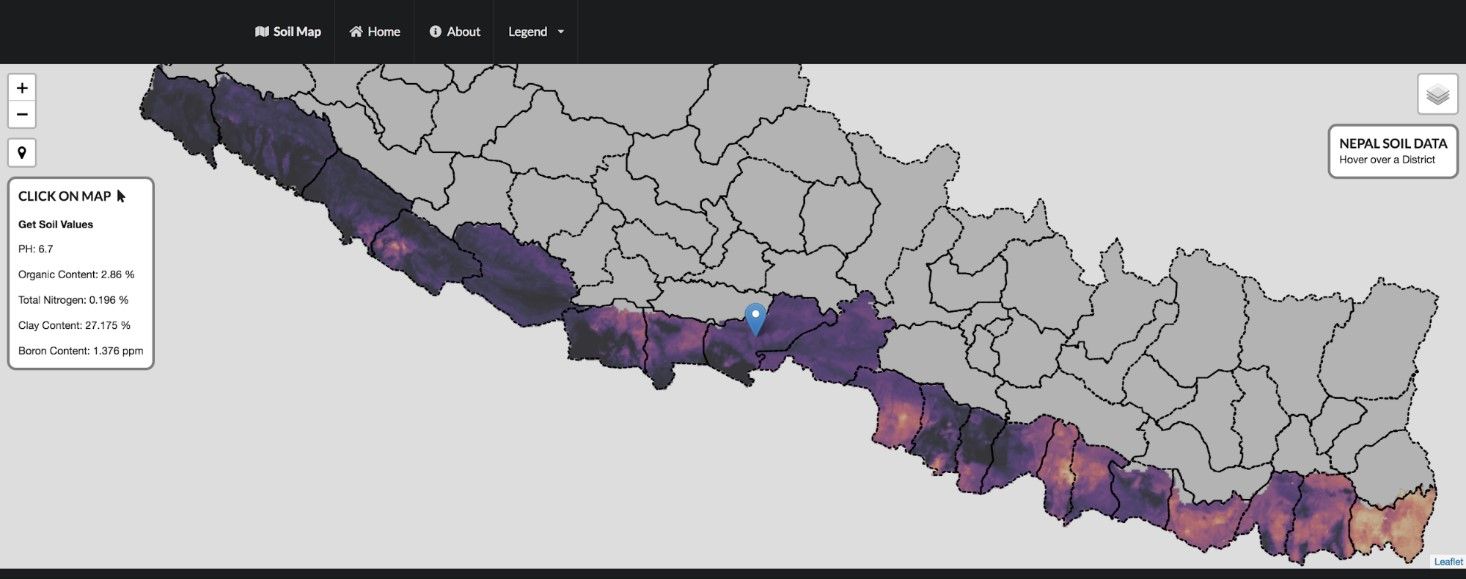

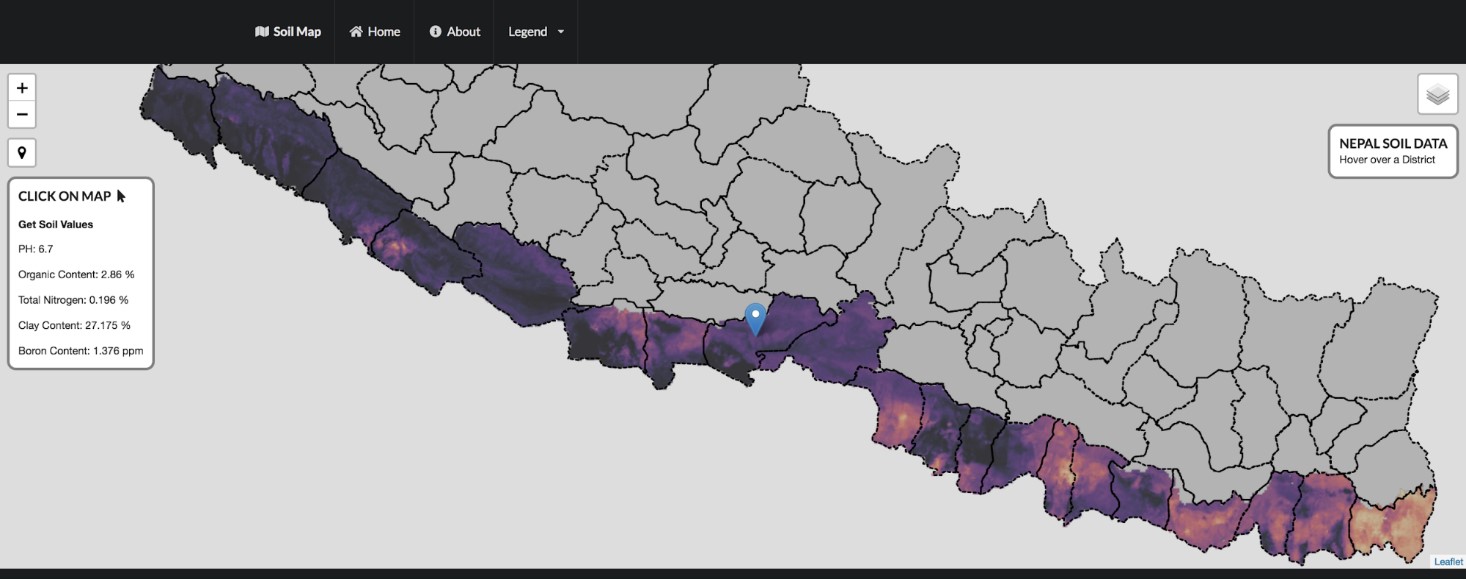

KATHMANDU, Nepal (CIMMYT) — The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is working with Nepal’s Soil Management Directorate and the Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC) to aggregate historic soil data and, for the first time in the country, produce

KATHMANDU, Nepal (CIMMYT) — The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is working with Nepal’s Soil Management Directorate and the Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC) to aggregate historic soil data and, for the first time in the country, produce