Dyutiman Choudhary

Dyutiman Choudhary is a Project Coordinator with the Nepal Seed and Fertilizer (NSAF) project.

For more information, contact CIMMYT’s Nepal office.

Dyutiman Choudhary is a Project Coordinator with the Nepal Seed and Fertilizer (NSAF) project.

The process for breeding for grain yield in bread wheat at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) involves three-stage testing at an experimental station in the desert environment of Ciudad Obregón, in Mexico’s Yaqui Valley. Because the conditions in Obregón are extremely favorable, CIMMYT wheat breeders are able to replicate growing environments all over the world and test the yield potential and climate-resilience of wheat varieties for every major global wheat growing area. These replicated test areas in Obregón are known as selection environments (SEs).

This process has its roots in the innovative work of wheat breeder and Nobel Prize winner Norman Borlaug, more than 50 years ago. Wheat scientists at CIMMYT, led by wheat breeder Philomin Juliana, wanted to see if it remained effective.

The scientists conducted a large quantitative genetics study comparing the grain yield performance of lines in the Obregón SEs with that of lines in target growing sites throughout the world. They based their comparison on data from two major wheat trials: the South Asia Bread Wheat Genomic Prediction Yield Trials in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh initiated by the U.S. Agency for International Development Feed the Future initiative and the global testing environments of the Elite Spring Wheat Yield Trials.

The findings, published in Retrospective Quantitative Genetic Analysis and Genomic Prediction of Global Wheat Yields, in Frontiers in Plant Science, found that the Obregón yield testing process in different SEs is very efficient in developing high-yielding and resilient wheat lines for target sites.

The authors found higher average heritabilities, or trait variations due to genetic differences, for grain yield in the Obregón SEs than in the target sites (44.2 and 92.3% higher for the South Asia and global trials, respectively), indicating greater precision in the SE trials than those in the target sites. They also observed significant genetic correlations between one or more SEs in Obregón and all five South Asian sites, as well as with the majority (65.1%) of the Elite Spring Wheat Yield Trial sites. Lastly, they found a high ratio of selection response by selecting for grain yield in the SEs of Obregón than directly in the target sites.

“The results of this study make it evident that the rigorous multi-year yield testing in Obregón environments has helped to develop wheat lines that have wide-adaptability across diverse geographical locations and resilience to environmental variations,” said Philomin Juliana, CIMMYT associate scientist and lead author of the article.

“This is particularly important for smallholder farmers in developing countries growing wheat on less than 2 hectares who cannot afford crop losses due to year-to-year environmental changes.”

In addition to these comparisons, the scientists conducted genomic prediction for grain yield in the target sites, based on the performance of the same lines in the SEs of Obregón. They found high year-to-year variations in grain yield predictabilities, highlighting the importance of multi-environment testing across time and space to stave off the environment-induced uncertainties in wheat yields.

“While our results demonstrate the challenges involved in genomic prediction of grain yield in future unknown environments, it also opens up new horizons for further exciting research on designing genomic selection-driven breeding for wheat grain yield,” said Juliana.

This type of quantitative genetics analysis using multi-year and multi-site grain yield data is one of the first steps to assessing the effectiveness of CIMMYT’s current grain yield testing and making recommendations for improvement—a key objective of the new Accelerating Genetic Gains in Maize and Wheat for Improved Livelihoods (AGG) project, which aims to accelerate the breeding progress by optimizing current breeding schemes.

This work was made possible by the generous support of the Delivering Genetic Gain in Wheat (DGGW) project funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) and managed by Cornell University; the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Feed the Future initiative; and several collaborating national partners who generated the grain yield data.

Read the full article: Retrospective Quantitative Genetic Analysis and Genomic Prediction of Global Wheat Yields

This story was originally posted on the website of the CGIAR Research Program on Wheat (wheat.org).

Cover photo: Wheat fields at CIMMYT’s Campo Experimental Norman E. Borlaug (CENEB) in Ciudad Obregón, Mexico. (Photo: CIMMYT)

“What you are now about to witness didn’t exist even a few years ago,” begins the first video in a series on zero tillage produced by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT). Zero tillage, an integral part of conservation agriculture-based sustainable intensification, can save farmers time, money and irrigation water.

Through storytelling, the videos demonstrate the process to become a zero till farmer or service provider: from learning how to prepare a field for zero tillage to the safe use of herbicides.

All videos are available in Bengali, Hindi and English.

This videos were produced as part of the Sustainable and Resilient Farming Systems Intensification in the Eastern Gangetic Plains (SRFSI) project, funded by the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR). The videos were scripted with regional partners and filmed with communities in West Bengal, India.

Conservation Agriculture Visual Syllabus (English):

Conservation Agriculture Visual Syllabus (Hindi):

Conservation Agriculture Visual Syllabus (Bengali):

More than 100 scientists, crop breeders, researchers, and representatives from funding and national government agencies gathered virtually to initiate the wheat component of a groundbreaking and ambitious collaborative new crop breeding project led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

The new project, Accelerating Genetic Gains in Maize and Wheat for Improved Livelihoods, or AGG, brings together partners in the global science community and in national agricultural research and extension systems to accelerate the development of higher-yielding varieties of maize and wheat — two of the world’s most important staple crops.

Funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the U.K. Department for International Development (DFID), the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research (FFAR), the project specifically focuses on supporting smallholder farmers in low- and middle-income countries. The international team uses innovative methods — such as rapid cycling and molecular breeding approaches — that improve breeding efficiency and precision to produce varieties that are climate-resilient, pest and disease resistant and highly nutritious, targeted to farmers’ specific needs.

The wheat component of AGG builds on breeding and variety adoption work that has its roots with Norman Borlaug’s Nobel Prize winning work developing high yielding and disease resistance dwarf wheat more than 50 years ago. Most recently, AGG builds on Delivering Genetic Gain in Wheat (DGGW), a 4-year project led by Cornell University, which ends this year.

“AGG challenges us to build on this foundation and make it better, faster, equitable and sustainable,” said CIMMYT Interim Deputy Director for Research Kevin Pixley.

At the virtual gathering on July 17, donors and partner representatives from target countries in South Asia joined CIMMYT scientists to describe both the technical objectives of the project and its overall significance.

“This program is probably the world’s single most impactful plant breeding program. Its products are used throughout the world on many millions of hectares,” said Gary Atlin from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. “The AGG project moves this work even farther, with an emphasis on constant technological improvement and an explicit focus on improved capacity and poverty alleviation.”

Alan Tollervey from DFID spoke about the significance of the project in demonstrating the relevance and impact of wheat research.

“The AGG project helps build a case for funding wheat research based on wheat’s future,” he said.

Nora Lapitan from the USAID Bureau for Resilience and Food Security listed the high expectations AGG brings: increased genetic gains, variety replacement, optimal breeding approaches, and strong collaboration with national agricultural research systems in partner countries.

Reconnecting with trusted partners

The virtual meeting allowed agricultural scientists and wheat breeding experts from AGG target countries in South Asia, many of whom have been working collaboratively with CIMMYT for years, to reconnect and learn how the AGG project both challenges them to a new level of collaboration and supports their national wheat production ambitions.

“With wheat blast and wheat rust problems evolving in Bangladesh, we welcome the partnership with international partners, especially CIMMYT and the funders to help us overcome these challenges,” said Director General of the Bangladesh Wheat and Maize Research Institute Md. Israil Hossain.

Director of the Indian Institute for Wheat and Barley Research Gyanendra P. Singh praised CIMMYT’s role in developing better wheat varieties for farmers in India.

“Most of the recent varieties which have been developed and released by India are recommended for cultivation on over 20 million hectares. They are not only stress tolerant and high yielding but also fortified with nutritional qualities. I appreciate CIMMYT’s support on this,” he said.

Executive Director of the National Agricultural Research Council of Nepal Deepak K. Bhandari said he was impressed with the variety of activities of the project, which would be integral to the development of Nepal’s wheat program.

“Nepal envisions increased wheat productivity from 2.84 to 3.5 tons per hectare within five years. I hope this project will help us to achieve this goal. Fast tracking the replacement of seed to more recent varieties will certainly improve productivity and resilience of the wheat sector,” he said.

The National Wheat Coordinator at the National Agricultural Research Center of Pakistan, Atiq Ur-Rehman, told attendees that his government had recently launched a “mega project” to reduce poverty and hunger and to respond to climate change through sustainable intensification. He noted that the support of AGG would help the country increase its capacity in “vertical production” of wheat through speed breeding. “AGG will help us save 3 to 4 years” in breeding time,” he said.

For CIMMYT Global Wheat Program Director Hans Braun, the gathering was personal as well as professional.

“I have met many of you over the last decades,” he told attendees, mentioning his first CIMMYT trip to see wheat programs in India in 1985. “Together we have achieved a lot — wheat self-sufficiency for South Asia has been secured now for 50 years. This would not be possible without your close collaboration, your trust and your willingness to share germplasm and information, and I hope this will stay. “

Braun pointed out that in this project, many national partners will gain the tools and capacity to implement their own state of the art breeding strategies such as genomic selection.

“We are at the beginning of a new era in breeding,” Braun noted. “We are also initiating a new era of collaboration.”

The wheat component of AGG serves more than 30 million wheat farming households in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, India, Kenya, Nepal and Pakistan. A separate inception meeting for stakeholders in sub-Saharan Africa is planned for next month.

Accelerating Genetic Gains in Maize and Wheat (AGG), a project led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), brings together partners in the global science community and in national agricultural research and extension systems to accelerate the development of higher-yielding varieties of maize and wheat — two of the world’s most important staple crops.

Specifically focusing on supporting smallholder farmers in low- and middle-income countries, the project uses innovative methods that improve breeding efficiency and precision to produce varieties that are climate-resilient, pest- and disease-resistant, and highly nutritious, targeted to farmers’ specific needs.

The maize component of the project serves 13 target countries: Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe in eastern and southern Africa; and Benin, Ghana, Mali, and Nigeria in West Africa. The wheat component of the project serves six countries: Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Pakistan in South Asia; and Ethiopia and Kenya in sub-Saharan Africa.

This project builds on the impact of the Delivering Genetic Gain in Wheat (DGGW) and Stress Tolerant Maize for Africa (STMA) projects.

Objectives

The project aims to accelerate the development and delivery of more productive, climate-resilient, gender-responsive, market-demanded, and nutritious maize and wheat varieties in support of sustainable agricultural transformation in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

To encourage adoption of new varieties, the project works to improve equitable access, especially by women, to seed and information, as well as capacity building in breeding, disease surveillance, and seed marketing.

Funders

Project funding is provided by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, the United States Agency for International Development and the Foundation for Food and Agricultural Research (FFAR).

Key partners

The primary partners for this project are the national agricultural research systems in the project target countries and, for the maize component, the International Institute for Tropical Agriculture (IITA) and small and medium enterprise (SME) seed companies.

Scientific and technical steering committees

We are grateful to our excellent maize and wheat scientific and technical steering committees for their suggestions and thoughtful question on key issues for the success of AGG. Read about the recommendations from the maize steering committee here and the wheat steering committee here.

Year 1 Executive Summary

In its first year of operation, AGG has made great strides in collaboration with our national partners towards the project goals –despite the unprecedented challenges of working through a global pandemic. For specific milestones achieved, we invite you to review our AGG Year 1 Executive Summary and Impact Report (PDF).

Year 2 Executive Summary

AGG has made progress towards all outcomes. Our scientists are implementing substantial modifications to breeding targets and schemes. AGG is also in a continuous improvement process for the partnership modalities, pursuing co-ownership and co-implementation that builds the capacities of all involved. For specific milestones achieved, we invite you to review our AGG Year 2 Executive Summary and Impact Report (PDF).

CIMMYT’s adult plant resistance breeding strategy

Download a summary of CIMMYT’s breeding strategy for adult plant resistance (PDF).

Subscribe to the AGG newsletter

Researchers from the Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA) project have been exploring the drivers of smallholder farmers’ underuse of groundwater wells to combat in-season drought during the monsoon rice season in Nepal’s breadbasket — the Terai region.

Their study, published in Water International, finds that several barriers inhibit full use of groundwater irrigation infrastructure.

Inconsistent rainfall has repeatedly damaged paddy crops in Nepal over the last years, even though most agricultural lands are equipped with groundwater wells. This has contributed to missed national policy targets of food self-sufficiency and slow growth in cereal productivity.

A key issue is farmers’ tendency to schedule irrigation very late in an effort to save their crops when in-season drought occurs. By this time, rice crops have already been damaged by lack of water and yields will be decreased. High irrigation costs, especially due to pumping equipment rental rates, are a major factor of this aversion to investment. Private irrigation is also a relatively new technology for many farmers making water use decisions.

After farmers decide to irrigate, queuing for pumpsets, tubewells, and repairs and maintenance further increases irrigation delays. Some villages have only a handful of pumpsets or tubewells shared between all households, so it can take up to two weeks for everybody to irrigate.

To address these issues, CSISA provides suggestions for three support pathways to support farmers in combatting monsoon season drought:

1. Raise awareness of the importance of timely irrigation

To avoid yield penalties and improve operational efficiency through better-matched pumpsets, CSISA has raised awareness through agricultural FM radio broadcasts on the strong relationship between water stress and yield penalties. Messages highlight the role of the plough pan in keeping infiltration rates low and encouraging farmers to improve irrigation scheduling. Anecdotal evidence suggests that improved pump selection may decrease irrigation costs by up to 50%, and CSISA has initiated follow-up studies to develop recommendations for farmers.

Social interaction is necessary for purchasing fuel, transporting and installing pumps, or sharing irrigation equipment. These activities pose risks of COVID-19 exposure and transmission and therefore require farmers to follow increased safety and hygiene practices, which may cause further delays to irrigation. Raising awareness about the importance of timely irrigation therefore needs to go hand in hand with the promotion of safe and hygienic irrigation practices. This information has been streamlined into CSISA’s ongoing partnerships and FM broadcasts.

2. Improve community-level water markets through increased focus on drought preparedness and overcoming financial constraints

Farmers can save time by taking an anticipatory approach to the terms and conditions of rentals, instead of negotiating them when cracks in the soil are already large. Many farmers reported that pump owners are reluctant to rent out pumpsets if renters cannot pay up front. Given the seasonality of cash flows in agriculture, pro-poor and low interest credit provisions are likely to further smoothen community-level water markets.

3. Prioritize regional investment

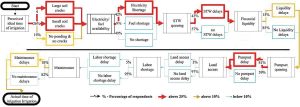

The study shows that delay factors differ across districts and that selectively targeted interventions will be most useful to provide high returns to investments. For example, farmers in Kailali reported that land access issues — due to use of large bullock carts to transport pumpsets — and fuel shortages constitute a barrier for 10% and 39% of the farmers, while in Rupandehi, maintenance and tubewell availability were reported to be of greater importance.

As drought is increasingly threatening paddy production in Nepal’s Terai region, CSISA’s research shows that several support pathways exist to support farmers in combatting droughts. Sustainable water use can only be brought up to a scale where it benefits most farmers if all available tools including electrification, solar pumps and improved water level monitoring are deployed to provide benefits to a wide range of farmers.

Read the study:

Drivers of groundwater utilization in water-limited rice production systems in Nepal

The agricultural market has been suffering since the government of Nepal imposed a lockdown from March 23, 2020 to limit the spread of COVID-19 in the country. A month after the lockdown, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) conducted a rapid assessment survey to gauge the extent of disruptions of the lockdown on households from farming communities and agribusinesses.

As part of the Nepal Seed and Fertilizer (NSAF) project, CIMMYT researchers surveyed over 200 key stakeholders by phone from 26 project districts. These included 103 agrovet owners and 105 cooperative managers who regularly interact with farming communities and provide agricultural inputs to farmers. The respondents served more than 300,000 households.

The researchers targeted maize growing communities for the survey since the survey period coincided with the primary maize season.

Key insights from the survey

The survey showed that access to maize seed was a major problem that farmers experienced since the majority of agrovets were not open for business and those that were partially open — around 23% — did not have much customer flow due to mobility restrictions during the lockdown.

The stock of hybrid seed was found to be less than open pollinated varieties (OPVs) in most of the domains. Due to restrictions on movement during the entire maize-planting season, many farmers must have planted OPVs or saved seeds.

Access to fertilizers such as urea, DAP and MOP was another major problem for farmers since more than half of the cooperatives and agrovets reported absence of fertilizer stock in their area. The stock of recommended pesticides to control pests such as fall armyworm was reported to be limited or out of stock at the cooperatives and agrovets.

Labor availability and use of agricultural machineries was not seen as a huge problem during the lockdown in the surveyed districts.

It was evident that food has been a priority for all household expenses. More than half of the total households mentioned that they would face food shortages if the lockdown continues beyond a month.

During the survey, around 36% of households specified cash shortages to purchase agricultural inputs, given that a month had already passed since the lockdown began in the country. The majority of the respondents reported that the farm households were managing their cash requirements by borrowing from friends and relatives, local cooperatives or selling household assets such as livestock and agricultural produces.

Most of the households said that they received food rations from local units called Palikas, while a small number of Palikas also provided subsidized seeds and facilitated transport of agricultural produce to market during the lockdown. Meanwhile, the type of support preferred by farming communities to help cope with the COVID-19 disruptions — ranging from food rations, free or subsidized seed, transportation of fertilizers and agricultural produce, and provision of credit — varied across the different domains.

The survey also assessed the effect of lockdown on agribusinesses like agrovets who are major suppliers of seed, and in a few circumstances sell fertilizer to farmers in Nepal. As the lockdown enforced restrictions on movement, farmers could not purchase inputs from agrovets even when the agrovets had some stock available in their area. About 86% of agrovets spoke of the difficulty to obtain supplies from their suppliers due to the blockage of transportation and product unavailability, thereby causing a 50-90% dip in their agribusinesses.

Immediate actions to consider

Major takeaways from this survey are as follows:

The survey findings were presented and shared with the government, private sector, development partner organizations and project staff over a virtual meeting. This report will serve as a resource for the project and various stakeholders to design their COVID-19 response and recovery strategy development and planning.

In response to increasing labor scarcity and costs, growth in mechanized wheat and rice harvesting has fueled farm prosperity and entrepreneurial opportunity in the poorest parts of Nepal, researchers from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) have recorded.

Farmers are turning to two-wheeled tractor-mounted reaper-harvesters to make up for the lack of farm labor, caused by a significant number of rural Nepalese — especially men and youth — migrating out in search of employment opportunities.

For Nandalal Oli, a 35-year-old farmer from Bardiya in far-west Nepal, investing in a mechanized reaper not only allowed him to avoid expensive labor costs that have resulted from out-migration from his village, but it also provided a source of income offering wheat and rice harvesting services to his neighbors.

“The reaper easily attaches on my two-wheel tractor and means I can mechanically cut and lay the wheat and rice harvests,” said Oli, the father of two. “Hiring help to harvest by hand is expensive and can take days but with the reaper attachment it’s done in hours, saving time and money.”

Oli was first introduced to the small reaper attachment three years ago at a farmer exhibition hosted by Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA), funded through USAID. He saw the reaper as an opportunity to add harvesting to his mechanization business, where he was already using his two-wheel tractor for tilling, planting and transportation services.

Prosperity powers up reaper adoption

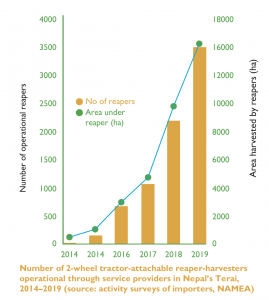

Over 4,000 mechanized reapers have been sold in Nepal with more than 50% in far and mid-west Nepal since researchers first introduced the technology five years ago. The successful adoption — which is now led by agricultural machinery dealers that were established or improved with CSISA’s support — has led nearly 24,000 farmers to have regular access to affordable crop harvesting services, said CIMMYT agricultural economist Gokul Paudel.

“Reapers improve farm management, adding a new layer of precision farming and reducing grain loss. Compared to manual harvesting mechanized reapers improve farming productivity that has shown to significantly increase average farm profitability when used for harvesting both rice and wheat,” he explained.

Nearly 65% of Nepal’s population works in agriculture, yet this South Asian country struggles to produce an adequate and affordable supply of food. The research indicated increased farm precision through the use of mechanized reapers boosts farm profitability by $120 a year when used for both rice and wheat harvests.

Oli agreed farmers see the benefit of his harvesting service as he has had no trouble finding customers. On an average year he serves 100 wheat and rice farmers in a 15 kilometer radius of his home.

“Investing in the reaper harvester worked for me. I earn 1,000 NRs [about $8] per hour harvesting fields and was able to pay off the purchase in one season. The added income ensures I can stay on top of bills and pay my children’s school fees.”

Farmers who have purchased reapers operate as service providers to other farms in their community, Paudel said.

“This has the additional benefit of creating legitimate jobs in rural areas, particularly needed among both migrant returnees who are seeking productive uses for earnings gained overseas that, at present, are mostly used for consumptive and unproductive sectors.”

“This additional work can also contribute to jobs for youth keeping them home rather than migrating,” he said.

The adoption rate of the reaper harvester is projected to reach 68% in the rice-wheat systems in the region within the next three years if current trends continue, significantly increasing access and affordability to the service.

Private and public support for mechanized harvester key to strong adoption

Achieving buy-in from the private and public sector was essential to the successful introduction and uptake of reaper attachments in Nepal, said Scott Justice, an agricultural and rural mechanization expert with the CSISA project.

Off the back of the popularity of the two-wheel tractor for planting and tilling, 22 reaper attachments were introduced by the researchers in 2014. Partnering with government institutions, the researchers facilitated demonstrations led by the private sector in farmers’ fields successfully building farmer demand and market-led supply.

“The reapers were introduced at the right place, at the right time. While nearly all Terai farmers for years had used tractor-powered threshing services, the region was suffering from labor scarcity or labor spikes where it took 25 people all day to cut one hectare of grain by hand. Farmers were in search of an easier and faster way to cut their grain,” Justice explained.

“Engaging the private and public sector in demonstrating the functionality and benefits of the reaper across different districts sparked rapidly increasing demand among farmers and service providers,” he said.

Early sales of the reaper attachments have mostly been directly to farmers without the need for considerable government subsidy. Much of the success was due to the researchers’ approach engaging multiple private sector suppliers and the Nepal Agricultural Machinery Entrepreneurs’ Association (NAMEA) and networks of machinery importers, traders, and dealers to ensure stocks of reapers were available at local level. The resulting competition led to 30-40% reduction in price contributing to increasing sales.

“With the technical support of researchers through the CSISA project we were able to import reaper attachments and run demonstrations to promote the technology as a sure investment for farmers and rural entrepreneurs,” said Krishna Sharma from Nepal Agricultural Machinery Entrepreneurs’ Association (NAMEA).

From 2015, the private sector capitalized on farmers’ interest in mechanized harvesting by importing reapers and running their own demonstrations and several radio jingles and sales continued to increase into the thousands, said Justice.

Building entrepreneurial capacity along the value chain

Through the CSISA project private dealers and public extension agencies were supported in developing training courses on the use of the reaper and basic business skills to ensure long-term success for farmers and rural entrepreneurs.

Training was essential in encouraging the emergence of mechanized service provision models and the market-based supply and repair chains required to support them, said CIMMYT agricultural mechanization engineer Subash Adhikari.

“Basic operational and business training for farmers who purchased a reaper enabled them to become service providers and successfully increased the access to reaper services and the amount of farms under improved management,” he said.

As commonly occurs when machinery adoption spreads, the availability of spare parts and repairs for reapers lagged behind sales. Researchers facilitated reaper repair training for district sales agent mechanics, as well as providing small grants for spare parts to build the value chain, Adhikari added.

Apart from hire services, mechanization creates additional opportunities for new business with repair and maintenance of equipment, sales and dealership of related businesses including transport and agro-processing along the value chain.

The Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA) aims to sustainably increase the productivity of cereal based cropping systems to improve food security and farmers’ livelihoods in Nepal. CSISA works with public and private partners to support the widespread adoption of affordable and climate-resilient farming technologies and practices, such as improved varieties of maize, wheat, rice and pulses, and mechanization.

Cover photo: A farmer uses a two-wheel tractor-mounted reaper to harvest wheat in Nepal. (Photo: Timothy J. Krupnik/CIMMYT)

Nearly 65,000 farmers in Nepal, 40% of which were women, have benefited from the Agronomy and Seed Systems Scaling project, according to a comprehensive new report. This project is part of the Cereals Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA), led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and supported by USAID.

One of the project’s most recent successes has been in accelerating the adoption of the nutritious and stress-tolerant mung bean in rice-wheat farming systems.

Rice-wheat is the dominant cropping system in the lowland region of Nepal. Farmers typically harvest wheat in March and transplant rice in July, leaving land fallow for up to 100 days. A growing body of evidence shows, however, that planting mung bean during this fallow period can assist in improving farmers’ farming systems and livelihoods.

“The mung bean has multiple benefits for farmers,” says Narayan Khanal, a researcher at CIMMYT. “The first benefit is nutrition: mung beans are very rich in iron, protein and are easily digestible. The second benefit is income: farmers can sell mung beans on the market for a higher price than most other legumes. The third benefit is improved soil health: mung beans fix the nitrogen from the atmosphere into the soil as well as improve soil organic content.”

Commonly used in dishes like dahl, soups and sprout, mung beans are a common ingredient in Asian cuisine. However, prior to the project, most farmers in Nepal had never seen the crop before and had no idea how to eat it. Encouraging them to grow the crop was not going to be an easy task.

Thanks to dedicated efforts by CIMMYT researchers, more than 8,000 farmers in Nepal are now cultivating mung bean on land that would otherwise be left fallow, producing over $1.75 million of mung bean per year.

The newfound enthusiasm for growing mung bean could not have been achieved without the help of local women’s farming groups, said Timothy J. Krupnik, CIMMYT senior scientist and CSISA project leader.

Bringing research and innovations to farmers’ fields

Introducing the mung bean crop to farmers’ fields was just one of the successes of Agronomy and Seed Systems Scaling, which was an added investment by USAID in the wider CSISA project, which began in 2014. The project aims to move agronomic and crop varietal research into real-world impact. It has helped farmers get better access to improved seeds and machinery and strengthened partnerships with the private sector, according to Khanal.

CSISA support in business mentoring and capacity building of seed companies to popularize newly released, biofortified and stress-tolerant wheat varieties has led to seed sales volumes tripling between 2014 to 2019. The project also led to a 68% increase in the number of new improved wheat varieties since the inception of the project.

Nepal’s National Wheat Research Program was able to fast track the release of the early maturing variety BL 4341, by combining data generated by the project through seed companies and the Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC) research station. Other varieties, including Borlaug 100 and NL 1327, are now in the pipeline.

Empowering women and facilitating women’s groups have been critical components of the project. Nepal has seen a mass exodus of young men farmers leaving the countryside for the city, leaving women to work the farms. CIMMYT worked with women farmer groups to expand and commercialize simple to use and affordable technologies, like precision seed and fertilizer spreaders.

Over 13,000 farmers have gained affordable access to and benefited from precision agriculture machinery such as two-wheel ‘hand tractors’ and ‘mini tillers.’ This is a major change for small and medium-scale farmers in South Asia who typically rely on low horsepower four-wheel tractors. The project also introduced an attachment for tractors for harvesting rice and wheat called the ‘reaper.’ This equipment helps to reduce the costs and drudgery of manual harvesting. In 2019, Nepal’s Terai region had almost 3,500 reapers, versus 22 in 2014.

To ensure the long-term success of the project, CSISA researchers have trained over 2,000 individuals from the private and public sector, and over 1,000 private organizations including machinery manufacturers and agricultural input dealers.

Researchers have trained project collaborators in both the public and private sector in seed systems, resilient varieties, better farming practices and appropriate agricultural mechanization business models. These partners have in turn passed this knowledge on to farmers, with considerable impact.

“The project’s outcomes demonstrates the importance of multi-year and integrated agricultural development efforts that are science-based, but which are designed in such a way to move research into impact and benefit farmers, by leveraging the skills and interests of Nepal’s public and private sector in unison,” said Krupnik.

“The outcomes from this project will continue to sustain, as the seed and market systems developed and nurtured by the project are anticipated to have long-lasting impact in Nepal,” he said.

Download the full report:

Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia: Agronomy and Seed Systems Scaling. Final report (2014-2019)

The Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA) is led by the International Maize and Wheat Center (CIMMYT), implemented jointly with the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). CSISA is funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Cover photo: A member of a women farmers group serves a platter of mung bean dishes in Suklaphanta, Nepal. (Photo: Merit Maharajan/Amuse Communication)

Dipak Kafle is a Business Development Analyst with CIMMYT’s Global Maize Program, based in Nepal.

Darbin Joshi is an Assistant Research Associate with CIMMYT’s Global Maize Program, based in Nepal.

Aashif Iqubal Khan is an Assistant Research Associate with CIMMYT’s Nepal Seed and Fertilizer Project, based in Nepal.

Nepalese and CIMMYT wheat scientists, working at the Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC) and the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre (CIMMYT) suspect new races of stripe and leaf rust infected the wheat crop in the Nepal hills and terai in the recent 2020 wheat season. This was reported after detailed survey and surveillance activities of rust diseases in the terai and hill regions were carried out during March and April, before the COVID-19 pandemic forced the cessation of many field activities.

Read more here: https://www.seedquest.com/news.php?type=news&id_article=117729&id_region=&id_category=&id_crop=

The use of small-scale mechanization in smallholder farming systems in South Asia has increased significantly in recent years. This development is a positive step towards agricultural transformation in the region. Small-scale mechanization is now seen as a viable option to address labor scarcity and offset the impact of male outmigration in rural areas, as well as other shortages that undermine agricultural productivity.

However, most existing farm mechanization technologies are either gender blind or gender neutral. This is often to the detriment of women farmers, who are increasingly taking on additional agricultural work in the absence of male laborers. Minimizing this gender disparity among smallholders has been a key concern for policymakers, but there is little empirical literature available on gender and farm mechanization.

A new study by researchers at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) addresses this gap, using data from six districts in the highlands of Nepal to assess the impact of the gender of household heads on the adoption of mini-tillers — small machinery used to prepare and cultivate land before planting.

Their findings reveal that, when it comes to mini-tiller adoption, there is a significant gender gap. Compared to male-headed households, explain the authors, the rate of adoption is significantly lower among female-headed households. Moreover, they add, when male- and female-headed households have similar observed attributes, the mini-tiller adoption rate among the food insecure female-headed households is higher than in the food secure group.

The authors argue that this gender-differentiated mini-tiller adoption rate can be minimized in the first instance by increasing market access. Their findings suggest that farm mechanization policies and programs targeted specifically to female-headed households can also help reduce this adoption gap in Nepal and similar hill production agroecologies in South Asia, which will enhance the farm yield and profitability throughout the region.

Read the full article in Technology in Society:

Gender differentiated small-scale farm mechanization in Nepal hills: An application of exogenous switching treatment regression.

See more recent publications from CIMMYT researchers:

The Asia Regional Resilience to a Changing Climate (ARRCC) program is managed by the UK Met Office, supported by the World Bank and the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID). The four-year program, which started in 2018, aims to strengthen weather forecasting systems across Asia. The program will deliver new technologies and innovative approaches to help vulnerable communities use weather warnings and forecasts to better prepare for climate-related shocks.

Since 2019, as part of ARRCC, CIMMYT has been working with the Met Office and Cambridge University to pilot an early warning system to deliver wheat rust and blast disease predictions directly to farmers’ phones in Bangladesh and Nepal.

The system was first developed in Ethiopia. It uses weather information from the Met Office, the UK’s national meteorological service, along with field and mobile phone surveillance data and disease spread modeling from the University of Cambridge, to construct and deploy a near real-time early warning system.

Phase I: 12-Month Pilot Phase

Around 50,000 smallholder farmers are expected to receive improved disease warnings and appropriate management advisories in the first 12 months as part of a proof-of-concept modeling and pilot advisory extension phase focused on three critical diseases:

Phase II: Scaling-out wheat rust early warning advisories, introducing wheat blast forecasting and refinement model refinement

Subject to funding approval the second year of the project will lead to validation of the wheat rust early warnings, in which researchers compare predictions with on-the-ground survey results, increasingly supplemented with farmer response on the usefulness of the warnings facilitated by national research and extension partners. Researchers shall continue to introduce and scale-out improved early warning systems for wheat blast. Concomitantly, increasing the reach of the advice to progressively larger numbers of farmers while refining the models in the light of results. We anticipate that with sufficient funding, Phase II activities could reach up to 300,000 more farmers in Nepal and Bangladesh.

Phase III: Demonstrating that climate services can increase farmers’ resilience to crop diseases

As experience is gained and more data is accumulated from validation and scaling-out, researchers will refine and improve the precision of model predictions. They will also place emphasis on efforts to train partners and operationalize efficient communication and advisory dissemination channels using information communication technologies (ICTs) for extension agents and smallholders. Experience from Ethiopia indicates that these activities are essential in achieving ongoing sustainability of early warning systems at scale. Where sufficient investment can be garnered to support the third phase of activities, it is expected that an additional 350,000 farmers will receive disease management warnings and advisories in Nepal and Bangladesh, totaling 1 million farmers over a three-year period.

Objectives