Hybrid seed production and marketing advances

“My goal is to produce and sell 200 metric tons of hybrid maize by 2025,” says Subash Raj Upadhyaya, chairperson of Lumbini Seed Company, based in Nepal’s Rupandehi district.

Upadhyaya is one of the few seed value chain actors in the country progressing in the hybrid seed sector, which is at a budding stage in Nepal. He envisions a significant opportunity in the domestic production of hybrid maize seed varieties that not only offer a higher yield than open-pollinated varieties but will also reduce expensive imports. Leaping from one hectare to 25 hectares in hybrid maize seed production within three years, Upadhyaya is determined to expand the local seed market for hybrids.

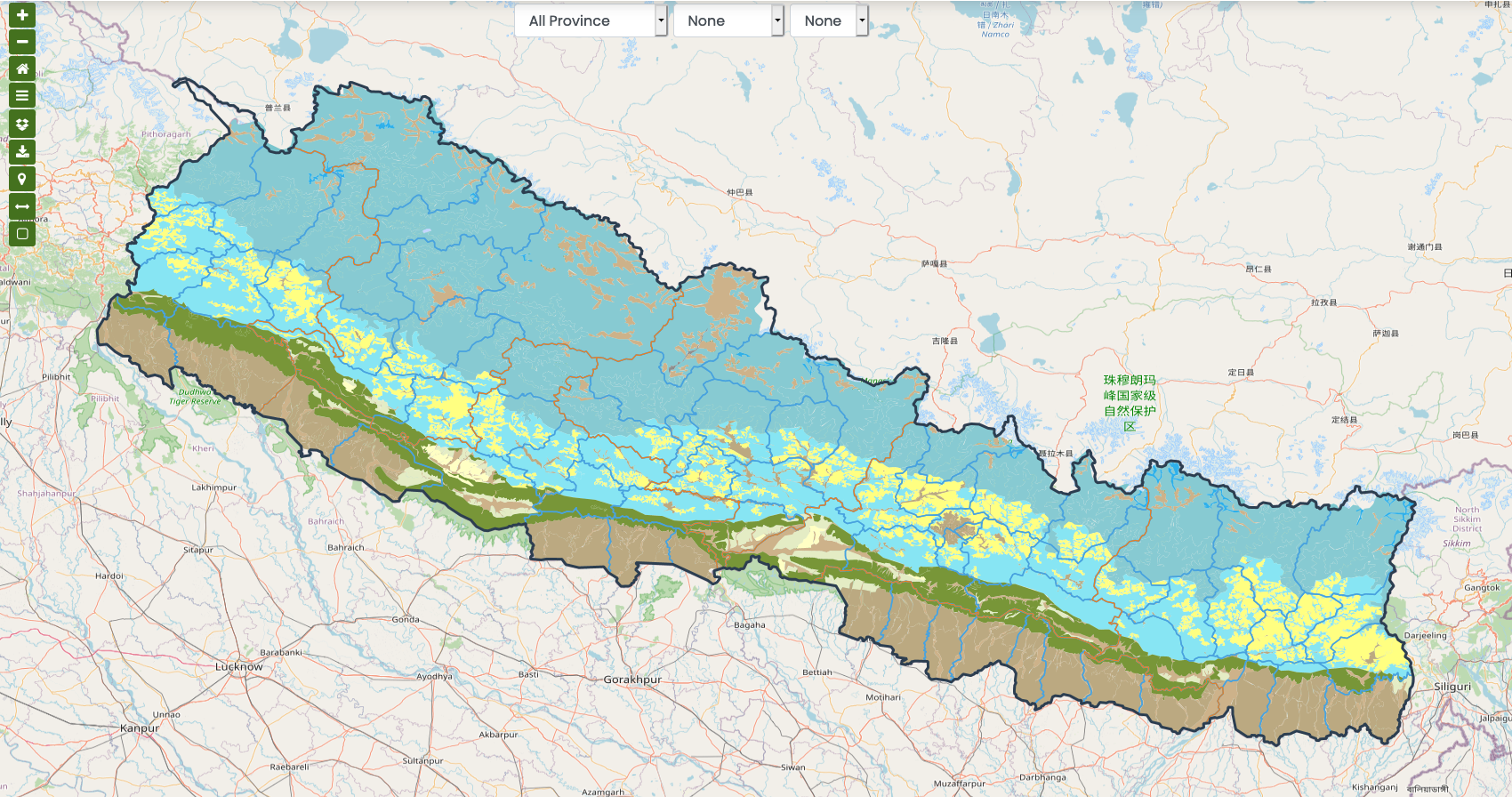

Nepal has long been a net importer of hybrid seeds — mainly rice, maize and high-value vegetables — worth millions of dollars a year to meet the farmers’ demand, which is continuously rising. Although hybrid varieties have been released in the country, organized local seed production and marketing were not in place to deliver quality seeds to farmers. The hybrid variety development process is relatively slow due to lack of strong public-private relationships, absence of enabling policies and license requirements for the private sector to produce and sell them, lack of suitable germplasm and inadequate skilled human resources for hybrid product development and seed production. This has resulted in poor adoption of hybrid seeds, especially maize, where only 10-15% out of 950,000 hectares of Nepal’s maize-growing area is estimated to be covered with hybrid seeds, leaving the balance for seeds of open pollinated varieties.

This is where experts from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) have stepped in to unlock the untapped potential of domestic maize production and increase on-farm productivity, which is currently around 2.8 metric tons per hectare. Aligning with the goals of the National Seed Vision (NSV 2013-2025), the USAID-funded Nepal Seed and Fertilizer (NSAF) project, implemented by CIMMYT, fosters private sector involvement in the evaluation, production and marketing of quality hybrid seeds to meet the growing domestic demand for grain production, which is currently being met via imports. In 2020, Nepal spent nearly $130 million to import maize grain for the poultry industry.

Teach a man to fish

Strengthening and scaling hybrid seed production of different crop varieties from domestic sources can be a game-changer for the long-term sustainability of Nepal’s seed industry.

Through the NSAF project, CIMMYT is working with eight partner seed companies and three farmers cooperatives to produce seeds of maize, rice and tomato. CIMMYT has played a vital role in making suitable germplasms and market-ready products of hybrids sourced from CGIAR centers available to the Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC) and partner seed companies for testing, validation and registration in the country. But this alone is not enough.

The project also carried out the partners’ capacity building on research and development, parental line maintenance, on-station and on-farm demonstrations, quality seed production and seed quality control to equip them with the required skills for a viable and competitive hybrid seed business. The companies and farmer cooperatives received hands-on training on hybrid seed production and marketing coupled with close supervision and guidance by the project’s field staff assigned to mentor and support individual seed companies. CIMMYT’s NSAF project also provides financial support to selected hybrid seed business startups to enhance their technical and entrepreneurial skills. This is a new feature, as prior to the project starting nearly all of the seed companies were mainly involved in aggregating open-pollinated variety seeds from farmers and selling them with no practical experience in the hybrid seed business.

In 2018, CIMMYT, through the NSAF and Heat Stress Tolerant Maize for Asia (HTMA) projects, and in close collaboration with NARC’s National Maize Research Program, engaged its partner seed company to initiate the first hybrid maize seed production during the winter season. Farmers’ feedback on the performance of the Rampur Hybrid-10 maize variety showed it could compete with existing commercial hybrids on yield and other commercial traits. As a result, this response boosted the confidence of seed companies and cooperatives to produce and market the hybrid seeds.

“I am very much motivated to be a hybrid maize seed producer for Lumbini Seed Company,” said a woman hybrid seed grower, whose income was 86% higher than the sale of maize grain from the previous season. “This is my second year of engagement, and last year I got an income of NPR 75,000 (approx. USD$652) from a quarter of a hectare. Besides the guaranteed market I have under the contractual agreement with the company, the profit is far higher than what I used to get from grain production.”

To build the competitiveness of the local seed sector, CIMMYT has been mentoring partner seed companies on business plan development, brand building, marketing and promotion, and facilitating better access to finance. As part of the intervention, the companies are now selling hybrid seeds through agro-dealers in attractive and suitable product packages of varied sizes designed to help boost seed sales, better shelf life and compete with imported brands. They have also started using attractive seed packages for selected open-pollinated rice varieties in a bid to increase market demand. Prior to the project’s intervention, companies used to sell their seeds in traditional unbranded jute bags which are less suitable to maintain seed quality.

Unite and conquer

Encouraging public-private partnerships for seed production is crucial for creating and maintaining a viable seed system. However, the existing guidelines and policies for variety registration are not private sector friendly, resulting in increased informal seed imports and difficulty to efficiently run a business. This draws attention to conducive policies and regulations patronage in research and varietal development, product registration, exclusive licensing, and seed production and marketing by the private sector.

CIMMYT supports the Seed Entrepreneurs Association of Nepal (SEAN), an umbrella body with more than 2,500 members, to promote the private sector’s engagement in the seed industry and foster enabling policies essential to further unlock Nepal’s potential in local hybrid seed production and distribution. Together, CIMMYT and SEAN have facilitated various forums, including policy dialogues and elicitations on fast track provision of R&D license and variety registration by the local private seed companies. These are vital steps to realize the targets set by NSV for hybrid seed development and distribution.

To further enhance linkages among seed sector stakeholders and policy makers, CIMMYT, in coordination with NARC’s National Maize Research Program, organized a high-level joint monitoring field visit to observe hybrid maize seed production performance in April 2021. As part of the visit, Yogendra Kumar Karki, Secretary of the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development, accompanied by representatives from the National Seed Board, National Planning Commission, Ministry of Finance, NARC, Seed Quality Control Center and SEAN, interacted with seed grower farmers and seed companies on their experiences.

The trip helped build a positive perception of the private sector’s capability and commitment to contribute to Nepal’s journey on self-reliance on hybrid seeds. “The recent advances in hybrid seed production by the private sector in collaboration with NARC and NSAF is astounding,” said Karki, as he acknowledged CIMMYT’s contribution to the seed sector development in Nepal. “Considering the gaps and challenges identified during this visit, the Ministry will revisit the regulations that will help accelerate local hybrid seed production and achieve NSV’s target.”

In continued efforts, CIMMYT is also partnering with the government’s Prime Minister Agricultural Modernization Project (PMAMP) maize super zone in the Dang district of Nepal to commercialize domestic maize hybrid seed by partner seed companies. This will enable companies to invest in hybrid maize seed production with contract growers by leveraging the support provided by the PMAMP on irrigation, mechanization and maize drying facilities.

“Our interventions in seed systems integration and coordination are showing very promising results in helping Nepal to become self-reliant on hybrid maize seeds in the foreseeable future,” said AbduRahman Beshir, seed systems lead for the NSAF project. “The initiative by the local seed companies to further engage and expand their hybrid seed business is an indication of a sustainable and viable project intervention. The project will continue working with both public and private partners to consolidate the gains and further build the competitiveness of the local seed companies in the hybrid maize seed ecosystem.”

Nepal’s seed industry is entering a new chapter that envisages a strong domestic seed sector in hybrid seed, particularly in maize, to capture a significant market share in the near future.