What’s the link between two-wheel tractors and elephants?

CIMMYT principal scientist Frédéric Baudron has two main research interests: making mechanization appropriate to smallholders and biodiversity conservation.

Wondering how these two intersect, a colleague of Baudron once asked him what the link was between an elephant and a tractor?

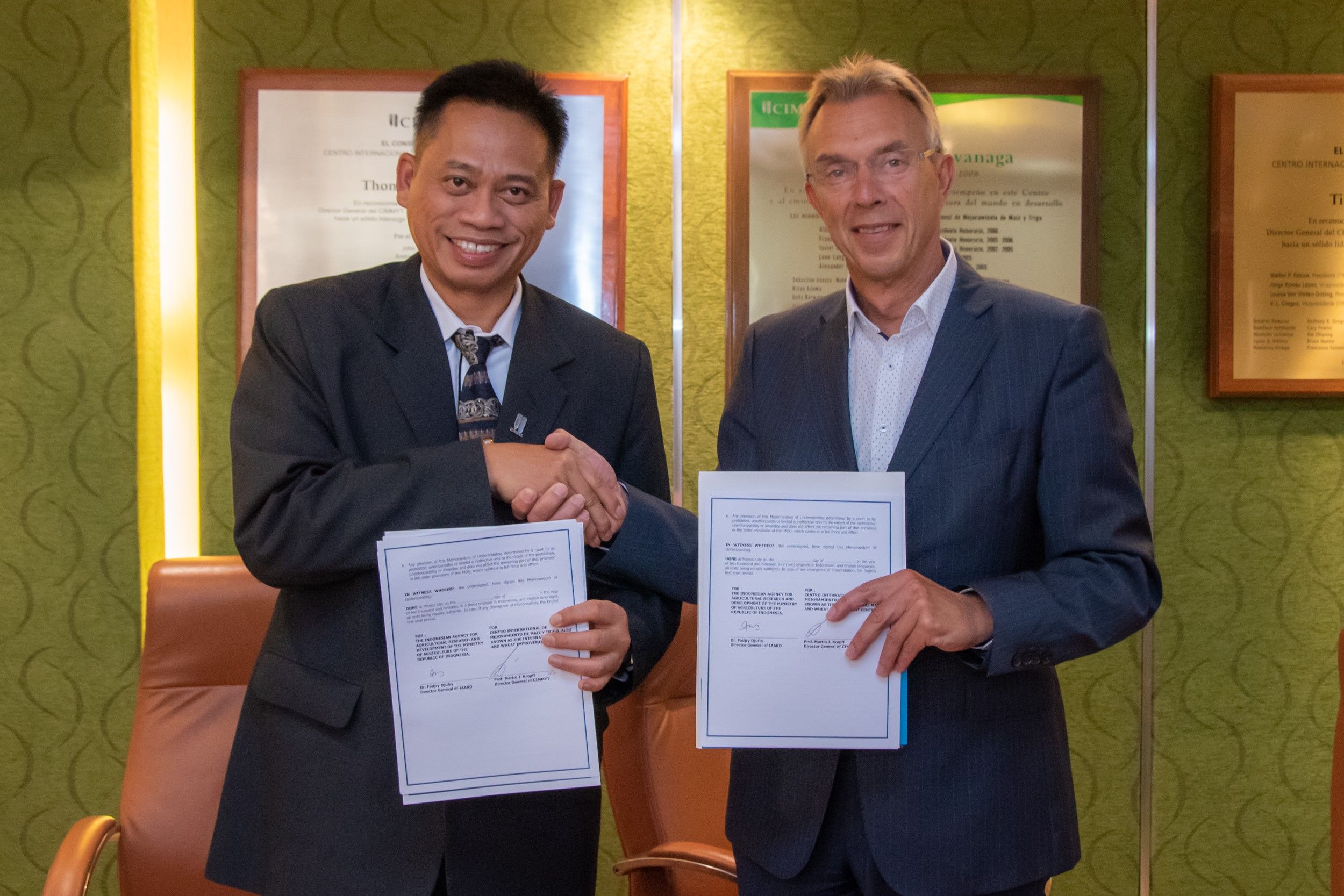

Now, in the recent report, “Addressing agricultural labour issues is key to biodiversity-smart farming research,” published in Biological Conservation, Baudron and other contributors have answered that question, examining trade-offs between labor and biodiversity conceptually, as well as in the specific context of Indonesia and Ethiopia.

This research continues work CIMMYT has done on the relationship between agriculture and biodiversity, including Commodity crops in biodiversity-rich production landscapes: Friends or foes? The example of cotton in the Mid Zambezi Valley, Zimbabwe and Sparing or sharing land? Views from agricultural scientists

Innovations in agricultural technology have led to undeniable achievements in reducing the physical labor needed to extract food from fields. Farm mechanization and technologies such as herbicides have increased productivity, but also became on the other hand major threats to biological diversity.

Adopting technologies that improve the productivity of labor benefits farmers in multiple ways, including a reduction of economic poverty, time poverty (i.e., lack of discretionary time, reducing labor drudgery), and child labor. Conversely, technologies that promote biodiversity often increase the burden of labor, leading to limited adoption by farmers. Therefore, there is a need to develop biodiversity-smart agricultural development strategies, which address biodiversity conservation goals and socio-economic goals, specifically raising land and labor productivity. This is especially true in the Global South, where population growth is rapid and much of the world’s remaining biodiversity is located.

“Without accounting for labor issues biodiversity conservation efforts will not be successful or sustainable,” said Baudron. “Because of this, we wanted to examine what biodiversity-smart agriculture might look like from a labor point of view.”

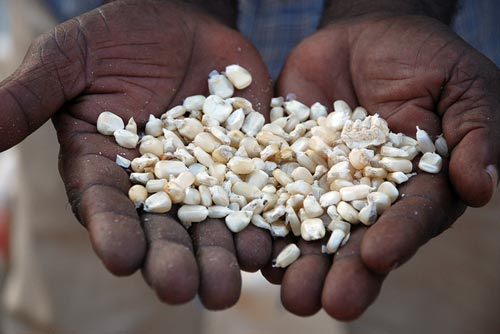

Research has quantified that farming families in Africa who use tractors expended an average of 640 labor hours per hectare in maize cultivation. In contrast, farmers not using tractors spent over 1100 hours for the same yield.

Trade-offs

While that is a clear win for reducing the heavy physical toil of farming, there are potential negative effects on biodiversity. In many countries in the Global North, the rise of tractors and other big machinery has led to larger and more rectangular fields and the removal of farm trees and hedgerows, all of which is associated with lower biodiversity. The same is now happening in parts of the Global South.

“A trade-off implies that one goal can only be achieved at the expense of another goal,” said Baudron. “It is not always a conscious choice; however, as farmers often adopt labor-saving techniques without considering the effects on biodiversity, simply because they lack options, and sometimes the necessary context.”

In Indonesia, the transition from harvesting rubber to producing palm oil has reduced the amount of physical labor, but biological diversity has decreased. However, innovations such as reducing fertilizer usage to avoid nutrient leaching into soil have been possible without compromising yield, and with the benefit of lower costs to farmers.

In Ethiopia, labor-saving technologies like the use of small-scale combine harvesters have been compatible with high biodiversity.

“I tell my colleagues a two-wheel tractor that allows mechanization with little negative environmental consequence (compatible with a mosaic of small, fragmented fields, with on-farm scattered trees, etc.) contributes to a landscape that works for people and biodiversity, including elephants,” said Baudron.

International Women’s Day on March 8, offers an opportunity to recognize the achievements of women worldwide. This year, CIMMYT asked readers to submit stories about women they admire for their selfless dedication to either maize or wheat. In the following story, Amanda Niode writes about her Super Woman of Maize, Asriani Anie Annisa Hasan of the Gorontalo Corn Information Center and Food Security Agency.

International Women’s Day on March 8, offers an opportunity to recognize the achievements of women worldwide. This year, CIMMYT asked readers to submit stories about women they admire for their selfless dedication to either maize or wheat. In the following story, Amanda Niode writes about her Super Woman of Maize, Asriani Anie Annisa Hasan of the Gorontalo Corn Information Center and Food Security Agency. “This project is a rare example of a public-private partnership capable of delivering products to farmers,” said Mike Robinson of the

“This project is a rare example of a public-private partnership capable of delivering products to farmers,” said Mike Robinson of the