Demonstration showcases maize hybrids

By O.P. Yadav/Indian Council of Agricultural Research

More than 120 researchers, policymakers and other stakeholders participated in a commercial hybrid demonstration and maize brainstorming sessions organized by the Directorate of Maize Research, Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR). The National Demonstration of Maize Commercial Hybrids and sessions were held 21-22 September in New Delhi.

The event demonstrated 106 maize hybrids, including leading hybrids from the public and private sectors. Visitors included S. Ayyappan, ICAR Director General; Ashish Bahuguna, secretary of the Department of Agriculture and Cooperation for the Government of India; H.S. Gupta, director of the Indian Agricultural Research Institute; B.S. Dhillon, vice chancellor of Punjab Agricultural University; J.S. Sandhu, commissioner of agriculture; R.P. Dua, assistant director general of food and fodder crops; J.S. Chauhan, assistant director general of seeds; S. Mauria, assistant director general of intellectual property & technology management; and more than 100 researchers from the national agricultural research system. P.H. Zaidi, B.S. Vivek and A.R. Sadananda from the Global Maize Program based in Hyderabad represented CIMMYT.

While visiting the demonstration, Ayyappan said he was impressed with the national maize program’s efforts to develop diverse maize hybrids that meet farmers’ needs in India’s different agro-ecological regions. He lauded the development and fine-tuning of maize production technology that has resulted in many improvements in the last decade. Bahuguna said the initiative was a unique showcase of hybrid technology that can improve farmers’ income. Providing farmers with a wide variety of hybrids can help achieve crop diversification in different regions, he noted. Bahuguna was also interested in new hybrids likely to be available to farmers in the near future.

Gupta emphasized the opportunities that exist to replace low-yielding, traditional maize varieties with hybrids, while Dhillon highlighted the importance of an effective seed production program to fully harness the hybrids’ benefits. Other topics included the objective of the demonstration and how to expand the scale of hybrid initiatives. Chauhan said the demonstration exhibited the strength of public research and development. Three brainstorming sessions – “Public-Private Partnerships,” “Trait Prioritization in Breeding” and “Improving Drought Tolerance” – followed the demonstration. They were led by S.K. Datta, deputy assistant director general for crop sciences, B.S. Dhillon and Sain Das, while Vivek and Zaidi contributed as panelists. More than 100 personnel from the public and private sectors participated. Datta underlined the role of both sectors and called upon scientists to identify areas where they can work together.

By S.P. Poonia/CIMMYT

By S.P. Poonia/CIMMYT

The training was for young scientists from different wheat research stations of India involved in a BMZ-funded project to increase the productivity of wheat under rising temperatures and water scarcity in South Asia. The training program attendees’ enhanced understanding of existing molecular tools for wheat breeding as well as emerging tools such as genomic selection. “Molecular tools will play an increasing role in wheat breeding to meet challenges in coming decades,” said Indu Sharma, director of DWR in Karnal. The program covered both theory and practice on the use of molecular makers in wheat breeding, especially those related to vernalization, photoperiodism and earliness per se, which could be used to enhance early heat tolerance. Practical sessions in the molecular laboratory of DWR focused on extraction of DNA, quantification and quality control of DNA, polymerase chain reaction polymerase chain reaction amplification and electrophoresis.

The training was for young scientists from different wheat research stations of India involved in a BMZ-funded project to increase the productivity of wheat under rising temperatures and water scarcity in South Asia. The training program attendees’ enhanced understanding of existing molecular tools for wheat breeding as well as emerging tools such as genomic selection. “Molecular tools will play an increasing role in wheat breeding to meet challenges in coming decades,” said Indu Sharma, director of DWR in Karnal. The program covered both theory and practice on the use of molecular makers in wheat breeding, especially those related to vernalization, photoperiodism and earliness per se, which could be used to enhance early heat tolerance. Practical sessions in the molecular laboratory of DWR focused on extraction of DNA, quantification and quality control of DNA, polymerase chain reaction polymerase chain reaction amplification and electrophoresis.

Introducing maize stover into India’s commercial dairy systems could mitigate fodder shortages and halt increasing fodder costs, according to new research by CIMMYT and the

Introducing maize stover into India’s commercial dairy systems could mitigate fodder shortages and halt increasing fodder costs, according to new research by CIMMYT and the  This dairy producer had maintained his eight improved Murrah buffaloes on a diet typical of that of urban and near-urban dairy systems in peninsular India. It consisted of 60% sorghum stover and 40% a homemade concentrate mix of 15% wheat bran, 54% cotton seed cake, and 31% husks and hulls from threshed pigeon-pea. Each of the dairy producer’s buffaloes consumed about 9.5 kg of sorghum stover and 6.5 kg of the concentrate mix per day and produced an average of 8.9 kg of milk per day. This dairy producer purchased sorghum stover at 6.3 Indian rupees (Rs) per kilogram. Together with the cost for concentrates, his feed cost totalled 18.2 Rs per kg of milk while his sale price was 28 Rs per kg of milk. In this trial, the dairy farmer purchased maize stover at 3.8 Rs per kg. When he substituted sorghum stover with maize stover, his average yield increased from 8.9 to 9.4 kg of milk per buffalo per day while his overall feed costs decreased from 18.2 to 14.5 Rs per kg of milk per day. The substitution of sorghum stover with maize increased his profits from 3.7 Rs per kg of milk, apart from an additional 0.5kg milk per buffalo.

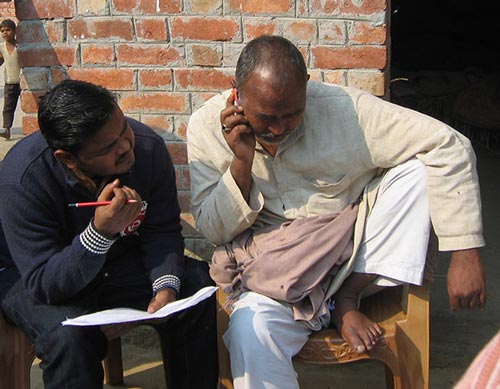

This dairy producer had maintained his eight improved Murrah buffaloes on a diet typical of that of urban and near-urban dairy systems in peninsular India. It consisted of 60% sorghum stover and 40% a homemade concentrate mix of 15% wheat bran, 54% cotton seed cake, and 31% husks and hulls from threshed pigeon-pea. Each of the dairy producer’s buffaloes consumed about 9.5 kg of sorghum stover and 6.5 kg of the concentrate mix per day and produced an average of 8.9 kg of milk per day. This dairy producer purchased sorghum stover at 6.3 Indian rupees (Rs) per kilogram. Together with the cost for concentrates, his feed cost totalled 18.2 Rs per kg of milk while his sale price was 28 Rs per kg of milk. In this trial, the dairy farmer purchased maize stover at 3.8 Rs per kg. When he substituted sorghum stover with maize stover, his average yield increased from 8.9 to 9.4 kg of milk per buffalo per day while his overall feed costs decreased from 18.2 to 14.5 Rs per kg of milk per day. The substitution of sorghum stover with maize increased his profits from 3.7 Rs per kg of milk, apart from an additional 0.5kg milk per buffalo. Mobile phones promise new opportunities for reaching farmers with agricultural information, but are their potential fully utilized? CIMMYT’s agricultural economist Surabhi Mittal and

Mobile phones promise new opportunities for reaching farmers with agricultural information, but are their potential fully utilized? CIMMYT’s agricultural economist Surabhi Mittal and  What can be done? Agro-advisory providers need to develop specific, appropriate, and timely content and update it as often as necessary. This cannot be achieved without a thorough assessment of farmers’ needs and their continuous evaluation. To ensure timeliness and accuracy of the provided information, two-way communication is necessary; Mittal and Mehar suggest the creation of helplines to provide customized solutions and enable feedback from farmers. The information delivery must be led by demand, not driven by supply. However, even when all that is done, it must be remembered that merely receiving messages over the phone does not motivate farmers to start using this information. The services have to be supplemented with demonstration of new technologies on farmers’ fields and through field trials.

What can be done? Agro-advisory providers need to develop specific, appropriate, and timely content and update it as often as necessary. This cannot be achieved without a thorough assessment of farmers’ needs and their continuous evaluation. To ensure timeliness and accuracy of the provided information, two-way communication is necessary; Mittal and Mehar suggest the creation of helplines to provide customized solutions and enable feedback from farmers. The information delivery must be led by demand, not driven by supply. However, even when all that is done, it must be remembered that merely receiving messages over the phone does not motivate farmers to start using this information. The services have to be supplemented with demonstration of new technologies on farmers’ fields and through field trials. Farmers need to be more involved in developing and refining technology. This was one of the key conclusions of a technology working group comprised of leading Asian scientists, representatives of farmer groups and entrepreneurs who met during “The 50 Pact,” an international conference jointly organized by the Borlaug Institute for South Asia (BISA) and the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) to celebrate 50 years of Dr. Norman Borlaug’s first visit to India. Held in New Delhi during 16-17 August, the event brought together more than 200 participants from agriculture institutions, the government, think tanks, industry, and civil society of various countries including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Belgium, Germany, India, Malaysia, Mexico, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and the United States.

Farmers need to be more involved in developing and refining technology. This was one of the key conclusions of a technology working group comprised of leading Asian scientists, representatives of farmer groups and entrepreneurs who met during “The 50 Pact,” an international conference jointly organized by the Borlaug Institute for South Asia (BISA) and the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) to celebrate 50 years of Dr. Norman Borlaug’s first visit to India. Held in New Delhi during 16-17 August, the event brought together more than 200 participants from agriculture institutions, the government, think tanks, industry, and civil society of various countries including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Belgium, Germany, India, Malaysia, Mexico, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and the United States. Technology and innovations will play a key role

Technology and innovations will play a key role  “Climatic extremes and variability are becoming more frequent and resulting in losses for farmers. This issue cannot be addressed in isolation; it needs collective participation of all stakeholders, at all levels,” stated Clare Stirling, leader of the CIMMYT component of the Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) CRP, at a stakeholder consultation on ‘Climate Smart Agricultural Technologies for Smallholder Farmers of Bihar’ held on 22 July 2013.

“Climatic extremes and variability are becoming more frequent and resulting in losses for farmers. This issue cannot be addressed in isolation; it needs collective participation of all stakeholders, at all levels,” stated Clare Stirling, leader of the CIMMYT component of the Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) CRP, at a stakeholder consultation on ‘Climate Smart Agricultural Technologies for Smallholder Farmers of Bihar’ held on 22 July 2013. The lively discussions included almost 200 participants, including innovative CSV farmers from Bhatthadasi, Rajapakar, and Mukundpur (Vaishali district); agriculture advisors from various Village Panchayats; climate smart farmer groups, research students, and local service providers. M.L. Jat, CIMMYT-CCAFS South Asia Leader, explained the concept of CCAFS CSVs in South Asia, and the key climate smart activities they are implementing for the benefit of smallholder farmers in Bihar’s Vaishali district. Participants visited demonstration plots where R.K. Jat, CIMMYT-BISA Cropping Systems Agronomist, showed how mechanization and conservation agriculture-based management practices are being implemented even on small, fragmented land holdings. By effectively ‘pooling’ their land for operational purposes, farmers have improved efficiency, reduced costs, and established timely crop management even with uncertain rainfall. R.K. Jat also explained the main advantages of the key climate smart interventions such as zero tillage, Direct Seeded Rice (DSR), raised bed planting, residue management, crop diversification, and nutrient management in managing climate risks and optimizing resources for higher profitability for the smallholders.

The lively discussions included almost 200 participants, including innovative CSV farmers from Bhatthadasi, Rajapakar, and Mukundpur (Vaishali district); agriculture advisors from various Village Panchayats; climate smart farmer groups, research students, and local service providers. M.L. Jat, CIMMYT-CCAFS South Asia Leader, explained the concept of CCAFS CSVs in South Asia, and the key climate smart activities they are implementing for the benefit of smallholder farmers in Bihar’s Vaishali district. Participants visited demonstration plots where R.K. Jat, CIMMYT-BISA Cropping Systems Agronomist, showed how mechanization and conservation agriculture-based management practices are being implemented even on small, fragmented land holdings. By effectively ‘pooling’ their land for operational purposes, farmers have improved efficiency, reduced costs, and established timely crop management even with uncertain rainfall. R.K. Jat also explained the main advantages of the key climate smart interventions such as zero tillage, Direct Seeded Rice (DSR), raised bed planting, residue management, crop diversification, and nutrient management in managing climate risks and optimizing resources for higher profitability for the smallholders. The active participation of about 80 female farmers allowed for a balanced and varied consultation. All the farmers expressed their concerns regarding climate variability and how it is affecting their livelihoods. They shared their experiences of turning their villages into CSVs, and how the new practices have benefitted them; after planting their wheat under zero till in the winter of 2012-13, farmers were initially skeptical of these changes to age-old practices, but having now reaped higher yields with less input costs, all the farmers have committed to planting under zero tillage next season. DSR has also been recently introduced, and the farmers thought the technology seemed promising in that it would reduce cultivation costs and provide some security under the increasing uncertainties of rainfall and labor shortages. The women farmers praised the intoduction of the ZT machine by CIMMYT under CCAFS. With many men migrating to cities, the women highlighted the reduced labor load with the increased availability of machinery and bed planting of maize and legumes.

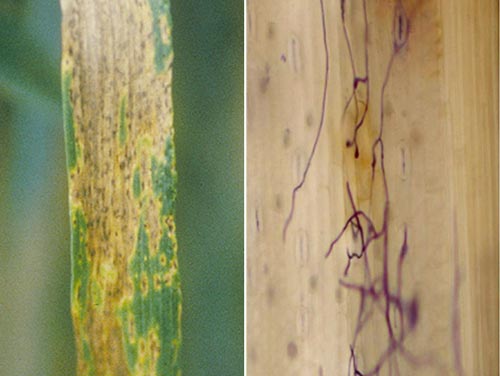

The active participation of about 80 female farmers allowed for a balanced and varied consultation. All the farmers expressed their concerns regarding climate variability and how it is affecting their livelihoods. They shared their experiences of turning their villages into CSVs, and how the new practices have benefitted them; after planting their wheat under zero till in the winter of 2012-13, farmers were initially skeptical of these changes to age-old practices, but having now reaped higher yields with less input costs, all the farmers have committed to planting under zero tillage next season. DSR has also been recently introduced, and the farmers thought the technology seemed promising in that it would reduce cultivation costs and provide some security under the increasing uncertainties of rainfall and labor shortages. The women farmers praised the intoduction of the ZT machine by CIMMYT under CCAFS. With many men migrating to cities, the women highlighted the reduced labor load with the increased availability of machinery and bed planting of maize and legumes. After screening some 500 wheat lines and varieties at 6 sites in Bangladesh, India, and Nepal, a group of scientists were able to identify 35 genotypes that resist spot blotch. This is the number-one disease of wheat in the Eastern Gangetic Plains, seriously damaging the crops of farmers—who are mostly smallholders—on some 9 million hectares.

After screening some 500 wheat lines and varieties at 6 sites in Bangladesh, India, and Nepal, a group of scientists were able to identify 35 genotypes that resist spot blotch. This is the number-one disease of wheat in the Eastern Gangetic Plains, seriously damaging the crops of farmers—who are mostly smallholders—on some 9 million hectares.