Bangladesh could largely reduce greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture while increasing efficiency in production

A number of readily-available farming methods could allow Bangladesh’s agriculture sector to decrease its greenhouse gas emissions while increasing productivity, according to a new study by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and partners.

The study, published in Science of the Total Environment, measured the country’s emissions due to agriculture, and identified and analyzed potential mitigation measures in crop and livestock farming. Pursuing these tactics could be a win-win for farmers and the climate, and the country’s government should encourage their adoption, the research suggests.

“Estimating the greenhouse gas emissions associated with agricultural production processes — complemented with identifying cost-effective abatement measures, quantifying the mitigation scope of such measures, and developing relevant policy recommendations — helps prioritize mitigation work consistent with the country’s food production and mitigation goals,” said CIMMYT climate scientist Tek Sapkota, who led this work.

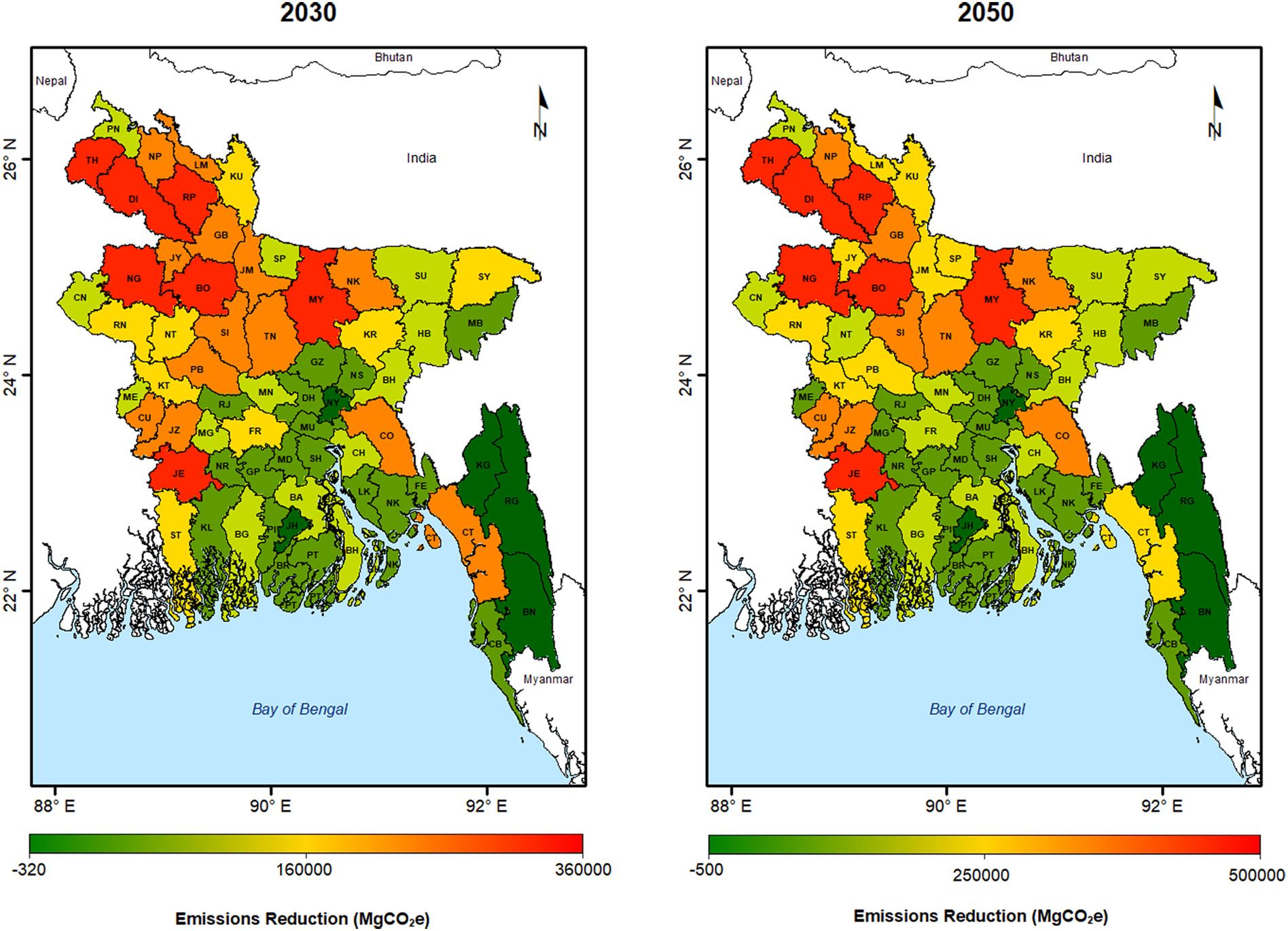

To determine Bangladesh’s agricultural greenhouse gas emissions, the researchers analyzed 16,413 and 12,548 datapoints from crops and livestock, respectively, together with associated soil and climatic information. The paper also breaks down the emissions data region by region within the country. This could help Bangladesh’s government prioritize mitigation efforts in the places where they will be the most cost-effective.

“I believe that the scientific information, messages and knowledge generated from this study will be helpful in formulating and implementing the National Adaptation Plan (NAP) process in Bangladesh, the National Action Plan for Reducing Short-Lived Climate Pollutants (SLCPs) and Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC),” said Nathu Ram Sarker, director general of the Bangladesh Livestock Research Institute.

Policy implications

Agriculture in Bangladesh is heavily intensified, as the country produces up to three rice crops in a single year. Bangladesh also has the seventh highest livestock density in the world. In all, the greenhouse gas output of agriculture in Bangladesh was 76.79 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (Mt CO2e) in 2014-15, according to the research. This emission is equivalent to the emission from fossil fuel burning by 28 million cars for a year. At the going rate, total agricultural emission from Bangladesh are expected to reach 86.87 Mt CO2e by 2030, and 100.44 Mt CO2e by 2050.

By deploying targeted and often readily-available methods, Bangladesh could mitigate 9.51 Mt and 14.21 Mt CO2e from its agriculture sector by 2030 and 2050, respectively, according to the paper. Further, the country can reach three-fourths of these outcomes by using mitigation strategies that also cut costs, a boon for smaller agricultural operations.

Adopting these mitigation strategies can reduce the country’s carbon emissions while contributing to food security and climate resilience in the future. However, realizing the estimated potential emission reductions may require support from the country’s government.

“Although Bangladesh has a primary and justified priority on climate change adaptation, mitigation is also an important national priority. This work will help governmental policy makers to identify and implement effective responses for greenhouse gas mitigation from the agricultural sector, with appropriate extension programs to aid in facilitating adoption by crop and livestock farmers,” said Timothy Krupnik, CIMMYT country representative in Bangladesh and coauthor of the paper.

Mitigation strategies

The research focused on eight crops and four livestock species that make up the vast majority of agriculture in Bangladesh. The crops — potato, wheat, jute, maize, lentils and three different types of rice — collectively cover more than 90% of cultivated land in the nation. Between 64 and 84% of total fertilizer used in Bangladesh is used to cultivate these crops. The paper also focuses on the four major kinds of livestock species in the country: cattle, buffalo, sheep and goats.

For crops, examples of mitigation strategies include alternate wetting and drying in rice (intermittently irrigating and draining rice fields, rather than having them continuously flooded) and improved nutrient use efficiency, particularly for nitrogen. The research shows that better nitrogen management could contribute 60-65% of the total mitigation potential from Bangladesh’s agricultural sector. Other options include adopting strip-tillage and using short duration rice varieties.

For livestock, mitigation strategies include using green fodder supplements, increased concentrate feeding and improved forage/diet management for ruminants. Improved manure storage, separation and aeration is another potential tool to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The mitigation options for livestock would make up 22 and 28% of the total potential emission reductions in the sector by 2030 and 2050, respectively.

RELATED RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS:

INTERVIEW OPPORTUNITIES:

Tek Sapkota, Agricultural Systems and Climate Change Scientist, CIMMYT

Tim Krupnik, Bangladesh Country Representative, CIMMYT

FOR MORE INFORMATION, OR TO ARRANGE INTERVIEWS, CONTACT THE MEDIA TEAM:

Marcia MacNeil, Interim Head of Communications, CIMMYT. m.macneil@cgiar.org

Rodrigo Ordóñez, Communications Manager, CIMMYT. r.ordonez@cgiar.org

ABOUT CIMMYT:

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is the global leader in publicly-funded maize and wheat research and related farming systems. Headquartered near Mexico City, CIMMYT works with hundreds of partners throughout the developing world to sustainably increase the productivity of maize and wheat cropping systems, thus improving global food security and reducing poverty. CIMMYT is a member of the CGIAR System and leads the CGIAR Research Programs on Maize and Wheat and the Excellence in Breeding Platform. The Center receives support from national governments, foundations, development banks and other public and private agencies. For more information, visit staging.cimmyt.org.