Bolivia and CIMMYT partner to boost sustainable grain production

By Ricardo Curiel/CIMMYT

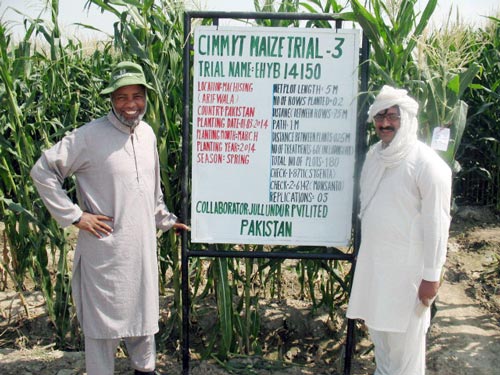

Bolivia became the first country in South America to adopt the sustainable intensification strategy for agriculture that CIMMYT has used successfully in Mexico with the Sustainable Modernization of Traditional Agriculture project (MasAgro), and in countries in Africa and Asia through similar projects. The project in Bolivia will develop new, high-yielding maize varieties adapted to the country’s growing conditions that will be commercialized by the local seed sector. The project also plans to develop and to transfer new technologies for sustainable farming practices based on conservation agriculture principles. “When combined, these factors account for higher and more stable yields, and contribute to mitigate agriculture’s impact on the environment,” said CIMMYT Director General Dr. Thomas A. Lumpkin.

The agreement was signed during the “Day of Collaborative Evaluation of Maize Research” organized by INIAF. Hans Mercado, INIAF Executive Director General, outlined the main activities planned for the three years of work that have been initially approved for the project. These include: analyses of commercial and family agriculture systems to improve their economic and ecologic performance; breeding of maize varieties adapted to Bolivia’s growing conditions; advice on the development of a seed production system that includes private and public players; and capacity building and training of human resources at different levels of specialization.

The ceremony was hosted by Bolivia’s Minister of Rural Development and Land, Nemesia Achacollo, who announced an investment of US$ 350,000 per year in the rural development project. She noted that the agreement was reached following her visit to CIMMYT earlier this year, when she had an opportunity to see and learn about MasAgro achievements in Mexico. Achacollo also stressed that INIAF had already introduced two maize hybrids developed by CIMMYT that yield seven tons per hectare, double the average yield obtained in Bolivia.

“CIMMYT celebrates Bolivia’s vision and leadership in investing in research for rural development,” said Lumpkin. “We hope that more countries in the region will follow Bolivia’s example and adopt similar strategies to strengthen food and nutritional security while also protecting the environment.”

To bolster maize exports to the European Union (EU), Peru is taking measures to ensure its grain is free from mycotoxins, according to CIMMYT maize pathologist Henry Ngugi. “They wanted to establish a testing mechanism because they are trading maize, for which they have to meet strict European Union (EU) standards. They have a project with CIMMYT, which brings them to me” explained Ngugi, who at the request of SENASA, the Peruvian National Agrarian Health Service, led a training course on the subject in Mexico from 21 October to 1 November.

To bolster maize exports to the European Union (EU), Peru is taking measures to ensure its grain is free from mycotoxins, according to CIMMYT maize pathologist Henry Ngugi. “They wanted to establish a testing mechanism because they are trading maize, for which they have to meet strict European Union (EU) standards. They have a project with CIMMYT, which brings them to me” explained Ngugi, who at the request of SENASA, the Peruvian National Agrarian Health Service, led a training course on the subject in Mexico from 21 October to 1 November.