Two approaches better than one: identifying spot blotch resistance in wheat varieties

Spot blotch, a major biotic stress challenging bread wheat production is caused by the fungus Bipolaris sorokiniana. In a new study, scientists from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) evaluate genomic and index-based selection to select for spot blotch resistance quickly and accurately in wheat lines. The former approach facilitates selecting for spot blotch resistance, and the latter for spot blotch resistance, heading and plant height.

Genomic selection

The authors leveraged genotyping data and extensive spot blotch phenotyping data from Mexico and collaborating partners in Bangladesh and India to evaluate genomic selection, which is a promising genomic breeding strategy for spot blotch resistance. Using genomic selection for selecting lines that have not been phenotyped can reduce the breeding cycle time and cost, increase the selection intensity, and subsequently increase the rate of genetic gain.

Two scenarios were tested for predicting spot blotch: fixed effects model (less than 100 molecular markers associated with spot blotch) and genomic prediction (over 7,000 markers across the wheat genome). The clear winner was genomic prediction which was on average 177.6% more accurate than the fixed effects model, as spot blotch resistance in advanced CIMMYT wheat breeding lines is controlled by many genes of small effects.

“This finding applies to other spot blotch resistant loci too, as very few of them have shown big effects, and the advantage of genomic prediction over the fixed effects model is tremendous”, confirmed Xinyao He, Wheat Pathologist and Geneticist at CIMMYT.

The authors have also evaluated genomic prediction in different populations, including breeding lines and sister lines that share one or two parents.

Index selection

One of the key problems faced by wheat breeders in selecting for spot blotch resistance is identifying lines that are genetically resistant to spot blotch versus those that escape and exhibit less disease by being late and tall. “The latter, unfortunately, is often the case in South Asia”, explained Pawan Singh, Head of Wheat Pathology at CIMMYT.

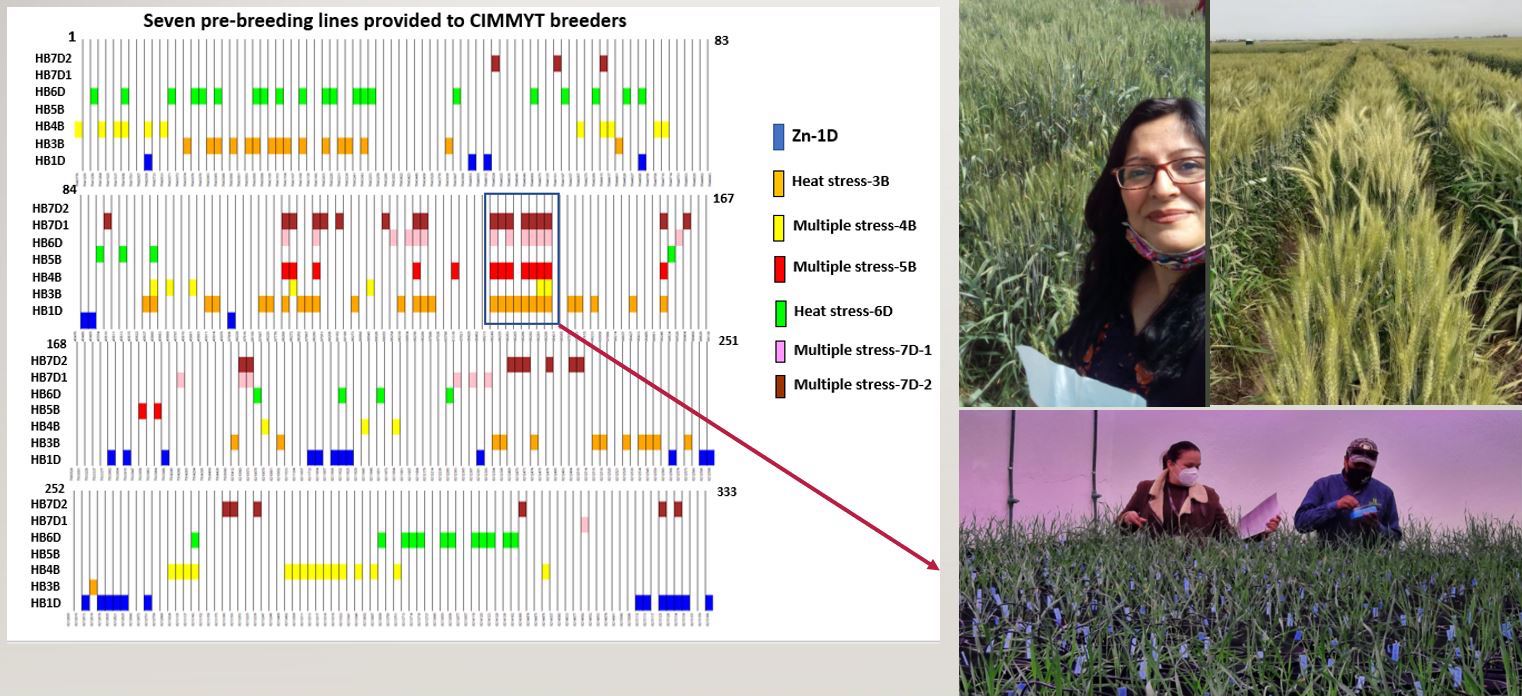

A potential solution to this problem is the use of selection indices that can make it easier for breeders to select individuals based on their ranking or predicted net genetic merit for multiple traits. Hence, this study reports the first successful evaluation of the linear phenotypic selection index and Eigen selection index method to simultaneously select for spot blotch resistance using the phenotype and genomic-estimated breeding values, heading and height.

This study demonstrates the prospects of integrating genomic selection and index-based selection with field based phenotypic selection for resistance in spot blotch in breeding programs.

Read the full study:

Genomic selection for spot blotch in bread wheat breeding panels, full-sibs and half-sibs and index-based selection for spot blotch, heading and plant height

Cover photo: Bipolaris sorokiniana, the fungus causing spot blotch in wheat. (Photo: Xinyao He and Pawan Singh/CIMMYT)