The late wheat breeder Norman Borlaug was so dedicated to his work that he was away from home 80 percent of the time, either travelling or in the field, recalls his daughter, Jeanie Borlaug Laube.

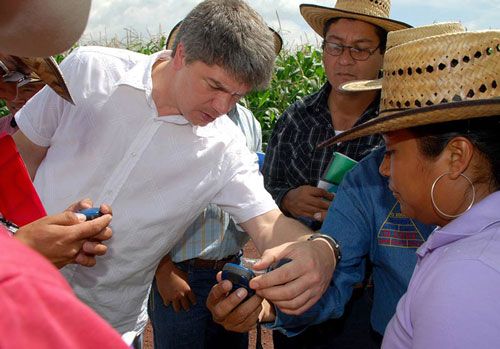

Photo: Alfredo Sáenz/CIMMYT

Scientist Borlaug, who died in 2009 at age 95, led efforts in the mid-20th century to develop high-yielding, disease resistant, semi-dwarf wheat varieties that helped save more than 1 billion lives in Pakistan, India and other areas of the developing world.

Wheat breeders, scientists and members of the global food security community celebrated his birthday at a week-long meeting hosted by CIMMYT in the vast wheat fields of the Yaqui Valley near the town of Ciudad Obregón in Mexico’s northern state of Sonora.

Each year, CIMMYT Visitors’ Week serves as an opportunity to brainstorm, exchange ideas and celebrate Borlaug’s legacy on the anniversary of his birthday.

Borlaug, who would have been 101 this year, started work on wheat improvement in the mid-1940s near CIMMYT headquarters outside Mexico City.

He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 partly for his experimental work, much of which took place in the hot, dry conditions of Obregón, which resemble conditions in many developing countries where CIMMYT works.

This year, his daughter, who is co-chair of the Borlaug Global Rust Initiative, a partnership to study and and control devastating stem, yellow and leaf wheat rust disease, spoke on women and agriculture at the event. She is also involved with the Jeanie Borlaug Laube Women in Triticum Mentor Award, which honors mentors of both genders who aid women working in Triticum species and near relatives. Additionally, she sits on the board of directors of the Borlaug Training Foundation, established to provide agricultural education and guidance to scientists from developing nations.

She shared her views in the following interview.

Q: What is your current involvement in agriculture?

I’m not officially in agriculture – I’m a Spanish teacher. I taught for 40 years in high school until I retired three years ago. In the last 25 years of my career I had started a community service program at two different schools in Dallas and ran it. This involves 750 kids a year out doing community service. I still taught one Spanish class but my basic job was community service director. I haven’t been involved in agriculture directly. Indirectly, I have been because I was Norman Borlaug’s daughter so I’ve been around it, but I wasn’t raised on a farm, never lived on a farm, didn’t study agriculture or science in school.

What is your current involvement with wheat?

I’m co-chair of the Borlaug Global Rust Initiative – I go to the conferences once a year where all the wheat scientists of the world get together. I go to all the conferences and sit and listen and try to learn and follow what is going on with rust and the different problems they are having with wheat. I’m involved with the Women in Triticum Award. I visit and follow up with them and they are the ones who are out in the field learning how to become scientists and continue the profession. That’s how I’m involved in wheat.

Q: What are your views on women in agriculture?

I was in Pakistan last year and the U.S. Department of Agriculture set up a meeting with women who were all scientists working on their doctoral degrees – or already had a Ph.D. in agriculture. The discussions were very interesting as far as the difficulties that women find in this field and the pluses and minuses that are involved with that. It was interesting to hear different aspects of what they were feeling. The academic studies were not a difficult thing for them, but the reality of raising a family and keeping a profession going and taking care of a husband or children at the same time as being away from home presented problems.

No matter what profession women are in, challenges confront them because we have to multi-task. It doesn’t matter whether you are an accountant, a geneticist or a teacher – as a mother or trying to run a family and a profession, I think it’s challenging for a lot of women.

Q: What impresses you about women in agriculture?

I’m always amazed at the women scientists who are out there working at these wheat conferences and out in the in the field and taking care of their families from afar or even before they get married or have children, just the dedication they have to helping feed the world.

Q: What are your views on food security?

I don’t think the general population has any clue as to what goes on with agriculture. As my dad used to say, everybody just thinks the food comes from the grocery store and that’s where it is – it just pops in there. The average person doesn’t have a clue about that.

Q: What has changed since your father’s time?

I imagine he’d be facing the same challenges. I think it would be really interesting if he were still around because he’d be going crazy right now with all of this fighting about gluten-free and over genetically modified plants. He was so dedicated. His mission was to feed the world.

I think it is still the same mission. I think it is probably just a little harder because you have more public opinion and lack of info for what you need. He was changing genes and they are still doing that and they need to because they need to find plants that require less fertilizer and less water and provide more protein. What is amazing to me is to think about how they are working with computers now and he did all this in his head with notebooks.

He’d leave home at five in the morning and get home at eight at night. When he was in town he was gone about 80 percent of the time. When he first started this shuttle breeding program he’d come to Sonora. That was in the 40s – he had to go up through Arizona and back down at first because there were no roads. He’d be up here for three months, then he’d go back down, then he’d go to Toluca and South America, then he started going to India and Pakistan. In later years he was going Africa, so he was never home.

Q: Where did you grow up?

I was raised in Mexico City. My brother was born in Mexico and I came here when I was 14 months old. I lived here until I went to college. I did my schooling down here.

Q: Did your father try and encourage women in science and agriculture?

Yes he did. Back then there weren’t very many women in agriculture and scence. I think he’d be very pleased to see the turn with what’s happening with women in agriculture.

Q: What is it like celebrating your father?

It’s really neat. When my dad realized that he was going to die he asked me to bring ashes back to Mexico so I did. The last two years we came before he died, we came in a private jet because he couldn’t travel. It was so hard to get here. I remember I looked at his face as we were approaching Obregón. His face was just pure relief. He loved this place and he’d see the wheat fields and it was magical for him. Coming back is kind of bittersweet, realizing how much he loved the farmers too as they loved him.

Nearly 140 members of the CIMMYT community and valued Mexican partners gathered on 16 April 2013 with the family of Gregorio “Goyo” Martínez Valdés, retired CIMMYT institutional relations officer who succumbed to cancer at 77 on 07 April, in a solemn ceremony in the pine grove at El Batán to commemorate his life and work.

Nearly 140 members of the CIMMYT community and valued Mexican partners gathered on 16 April 2013 with the family of Gregorio “Goyo” Martínez Valdés, retired CIMMYT institutional relations officer who succumbed to cancer at 77 on 07 April, in a solemn ceremony in the pine grove at El Batán to commemorate his life and work. “He had a big heart, divided into clear portions, and CIMMYT occupied a big chunk,” said Martínez’s son Francisco, who noted his father’s supreme love for work and colleagues. He also brought a portion of his father’s ashes and bequeathed them to CIMMYT.

“He had a big heart, divided into clear portions, and CIMMYT occupied a big chunk,” said Martínez’s son Francisco, who noted his father’s supreme love for work and colleagues. He also brought a portion of his father’s ashes and bequeathed them to CIMMYT.

National Service Seed Inspection and Certification (

National Service Seed Inspection and Certification ( CIMMYT participated in the fair through its Seeds of Discovery (SeeD) initiative under the Genetic Resources Program. Martha Willcox (SeeD maize phenotyping coordinator) and Carolina Saint Pierre (SeeD wheat phenotyping coordinator) presented maize and wheat collections from the CIMMYT genebank and a poster prepared by Paulina González and Bibiana Espinosa from the germplasm bank emphasizing the importance of seed conservation and its long-term benefits for humanity. CIMMYT team was also represented by Isabel Peña, Institutional Relations Head, who provided visitors with information on CIMMYT. The CIMMYT booth was visited by many students, professors, and farmers. The students and professors expressed a particular interest in CIMMYT’s publications on maize and wheat diseases, conservation agriculture, the SeeD initiative, breeding for drought and low nitrogen tolerance, breeding of native maize (criollos), and grain storage techniques. Farmers were mostly interested in CIMMYT maize collections samples. They also shared their experience working with different types of maize.

CIMMYT participated in the fair through its Seeds of Discovery (SeeD) initiative under the Genetic Resources Program. Martha Willcox (SeeD maize phenotyping coordinator) and Carolina Saint Pierre (SeeD wheat phenotyping coordinator) presented maize and wheat collections from the CIMMYT genebank and a poster prepared by Paulina González and Bibiana Espinosa from the germplasm bank emphasizing the importance of seed conservation and its long-term benefits for humanity. CIMMYT team was also represented by Isabel Peña, Institutional Relations Head, who provided visitors with information on CIMMYT. The CIMMYT booth was visited by many students, professors, and farmers. The students and professors expressed a particular interest in CIMMYT’s publications on maize and wheat diseases, conservation agriculture, the SeeD initiative, breeding for drought and low nitrogen tolerance, breeding of native maize (criollos), and grain storage techniques. Farmers were mostly interested in CIMMYT maize collections samples. They also shared their experience working with different types of maize. In order to define the research priorities for the Seeds of Discovery initiative in maize quality of landraces (a Strategic Initiative of both CRPs MAIZE and WHEAT funded by Mexico), a diverse group of food scientists, chemists, maize breeders, genebank curators, social scientists, and representatives of research institutions such as UNAM and Chapingo, met for a workshop to discuss future research on quality characteristics within native Mexican maize.

In order to define the research priorities for the Seeds of Discovery initiative in maize quality of landraces (a Strategic Initiative of both CRPs MAIZE and WHEAT funded by Mexico), a diverse group of food scientists, chemists, maize breeders, genebank curators, social scientists, and representatives of research institutions such as UNAM and Chapingo, met for a workshop to discuss future research on quality characteristics within native Mexican maize.