Preserving native maize and culture in Mexico

Felipa Martinez, an indigenous Mexican grandmother, grins as she shows off a bag bulging with maize cobs saved from last harvest season. With her family, she managed to farm enough maize for the year despite the increasing pressure brought by climate change.

Felipa’s grin shows satisfaction. Her main concern is her family, the healthy harvest lets her feed them without worry and sell the little left over to cover utilities.

“When our crops produce a good harvest I am happy because we don’t have to spend our money on food. We can make our own tortillas and tostadas,” she said.

Her family belongs to the Chatino indigenous community and lives in the small town of Santiago Yaitepec in humid southern Oaxaca. They are from one of eleven marginalized indigenous communities throughout the state involved in a participatory breeding project with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) to naturally improve the quality and preserve the biodiversity of native maize.

These indigenous farmers are custodians of maize biodiversity, growing seeds passed down over generations. Their maize varieties represent a portion of the diversity found in the 59 native Mexican races of maize, or landraces, which first developed from wild grasses at the hands of their ancestors. These different types of maize diversified through generations of selective breeding, adapting to the environment, climate and cultural needs of the different communities.

In recent years, a good harvest has become increasingly unreliable, as the impacts of climate change, such as erratic rainfall and the proliferation of pests and disease, have begun to challenge native maize varieties. Rural poor and smallholder farmers, like Martinez and her family, are among the hardest hit by the mounting impacts of climate change, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

These farmers and their ancestors have thousands of years of experience selecting and breeding maize to meet their environment. However, climate change is at times outpacing their selection methods, said CIMMYT landrace improvement coordinator Martha Willcox, who works with the community and coordinates the participatory breeding project. Through the initiative, the indigenous communities work together with professional maize breeders to continuously improve and conserve their native maize.

Despite numerous challenges, farmers in the region are unwilling to give up their maize for other varieties. “The native maize, my maize grows best here, it yields well in our environment. The maize is sweeter, it is heavier,” said Don Modesto Suarez, Felipa’s husband. “This maize has been grown by our grandfathers and this is why I will not change it.”

This is because a community’s native maize varieties are adapted to their specific microclimate, such as elevation and weather patterns, and therefore may perform better or be more resistant to local pests and diseases than other maize varieties. They may also have specific characteristics prized for local culinary traditions — for example, in Santiago Yaitepec the native maize varieties have a specific type of starch that allows for the creation of extra-large tortillas and tostadas that are in high demand in local markets.

Other varieties may not meet farmers’ specific needs or climate, and many families do not want to give up their cultural attachment to native maize, said Flavio Aragon, a genetic resources researcher at the Mexican National Institute for Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock Research (INIFAP) who collaborates with Willcox.

CIMMYT and INIFAP launched the four-year participatory plant breeding project to understand marginalized communities’ unique makeup and needs – including maize type, local climates, farming practices, diseases and culture – and include farmers in breeding maize to suit these needs.

“Our aim is to get the most out of the unique traits in the native maize found in the farmer’s fields. To preserve and use it to build resistance and strength without losing the authenticity,” said Aragon.

“When we involve farmers in the process of selection, they are watching what we are doing and they are learning techniques,” he said. “Not only about the process of genetic selection in breeding but also sustainable farming practices and this makes it easier for farmers to adopt the maize that they have worked alongside breeders to improve through the project.”

Suarez said he appreciates the help, “We are learning how to improve our maize and identify diseases. I hope more farmers in the community join in and grow with us,” he said.

When disease strikes

Changes in weather patterns due to climate change are making it hard for farmers to know when to plant their crops to avoid serious disease. Now, a fungal disease known as tar spot complex, or TSC, is increasingly taking hold of maize crops, destroying harvests and threatening local food security, said Willcox. TSC resistance is one key trait farmers want to include in the participatory breeding.

Named for the black spots that cover infected plants, TSC causes leaves to die prematurely, weakening the plant and preventing the ears from developing fully, cutting yields by up to 50 percent or more in extreme cases.

Caused by a combination of three fungal infections, the disease occurs most often in cool and humid areas across southern Mexico, Central America and into South America. The disease is beginning to spread, possibly due to climate change, evolving pathogens and introduction of susceptible maize varieties.

“Our maize used to grow very well here, but then this disease came and now our maize doesn’t grow as well,” said Suarez. “For this reason we started to look for maize that we could exchange with our neighbors.”

A traditional breeding method for indigenous farmers is to see what works in fields of neighboring farmers and test it in their own, Willcox said.

Taking the search to the next level, Willcox turned to the CIMMYT Maize Germplasm Bank, which holds over 7000 native maize seed types collected from indigenous farmers. She tested nearly a thousand accessions in search of TSC resistance. A tedious task that saw her rate the different varieties on how they handled the disease in the field. However, the effort paid off with her team discovering two varieties that stood up to the disease. One variety, Oaxaca 280, originated from just a few hours north of where the Suarez family lives.

After testing Oaxaca 280 in their fields the farmers were impressed with the results and have now begun to include the variety in their breeding.

“Oaxaca 280 is a landrace – something from Mexico – and crossing this with the community’s maize gives 100 percent unimproved material that is from Oaxaca very close to their own,” said Willcox. “It is really a farmer to farmer exchange of resistance from another area of Oaxaca to this landrace here.”

“The goal is to make it as close as it can be to what the farmer currently has and to conserve the characteristics valued by farmers while improving specific problems that the farmers request help with, so that it is still similar to their native varieties and they accept it,” Aragon said.

Expanding for impact

Willcox and colleagues throughout Mexico seek to expand the participatory breeding project nationwide in a bid to preserve maize biodiversity and support rural communities.

“If you take away their native maize you take away a huge portion of the culture that holds these communities together,” said Willcox. Participatory breeding in marginalized communities preserves maize diversity and builds rural opportunities in areas that are hotbeds for migration to the United States.

“A lack of opportunities leads to migration out of Mexico to find work in other places, a strong agricultural sector means strong rural opportunities,” she said.

To further economic opportunities in the communities, these researchers have been connecting farmers with restaurant owners in Mexico City and the United States to export surplus grain and support livelihoods. A taste for high-quality Mexican food has created a small but growing market for the native maize varieties.

Native maize hold the building blocks for climate-smart crops

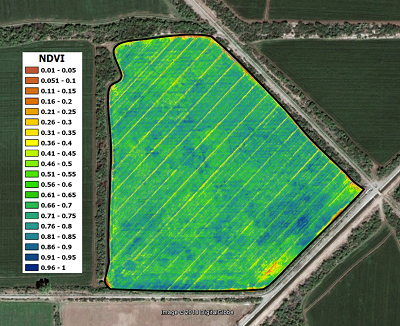

Native maize varieties show remarkable diversity and climate resilience that grow in a range from arid to humid environments, said Willcox. The genetic traits found in this diversity are the building blocks that can be used to develop varieties suitable for the changing crop environments predicted for 2050.

“There is a lot of reasoning that goes into the way that these farmers farm the land, the way they decide on what they select for,” said Willcox. “This has been going on for years and has been passed down through generations. For this reason, they have maize of such high quality with resistance to local challenges, genetic traits that now can be used to create strong varieties to help farmers in Mexico and around the world.”

It is key to analyze the genetic variability of native maize, and support the family farmers who conserve it in their fields, she added. This biodiversity still sown and selected throughout diverse microclimates of Mexico holds the traits we need to protect our food supplies.

To watch a video on CIMMYT’s work in this community, please click here.

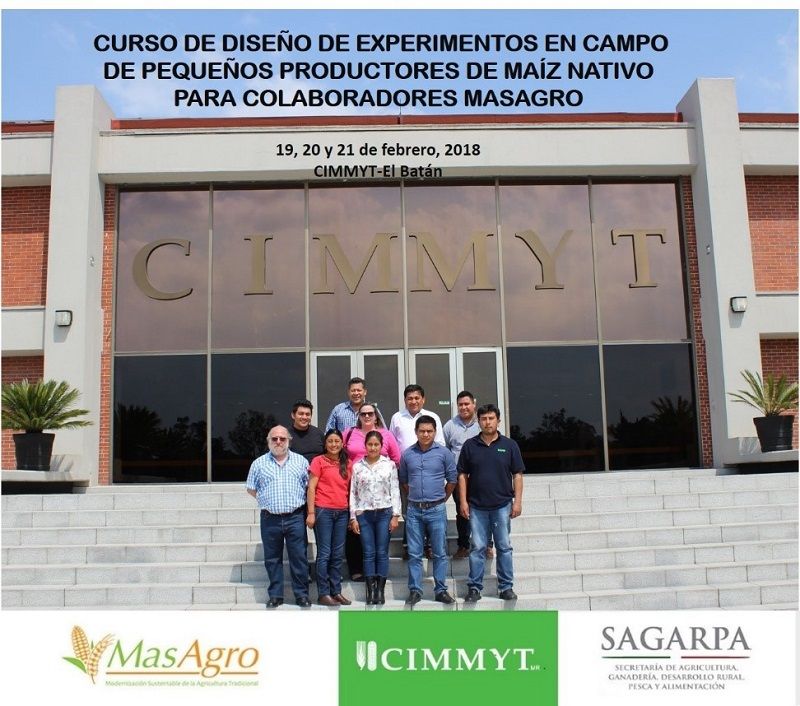

This work has been conducted as part of the CIMMYT-led MasAgro project in collaboration with INIFAP, and supported by Mexico’s Department of Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries and Food (SAGARPA) and the CGIAR Research Program MAIZE.

Increasingly erratic weather, poor soil health, and resource shortages brought on by climate change are challenging the ability of farmers in developing countries to harvest a surplus to sell or even to grow enough to feed their households. A healthy crop can mean the difference between poverty and prosperity, between hunger and food security.

Increasingly erratic weather, poor soil health, and resource shortages brought on by climate change are challenging the ability of farmers in developing countries to harvest a surplus to sell or even to grow enough to feed their households. A healthy crop can mean the difference between poverty and prosperity, between hunger and food security.

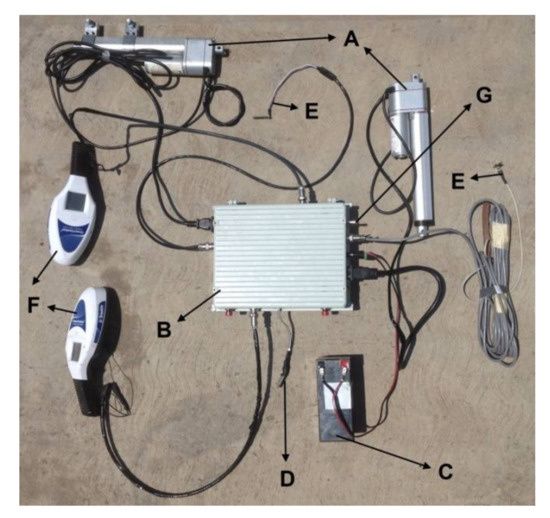

As part of the efforts of the Sustainable Modernization of Traditional Agriculture (MasAgro) program aimed at improving food security based on maize landraces in marginal areas of the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, a workshop on trial design was held from 19-21 February to improve the precision of data on improved maize landraces in smallholder farmers’ fields. Attending the workshop were partners from the National Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock Research Institute (INIFAP) and the Southern Regional University Center of the Autonomous University of Chapingo (UACh).

As part of the efforts of the Sustainable Modernization of Traditional Agriculture (MasAgro) program aimed at improving food security based on maize landraces in marginal areas of the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, a workshop on trial design was held from 19-21 February to improve the precision of data on improved maize landraces in smallholder farmers’ fields. Attending the workshop were partners from the National Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock Research Institute (INIFAP) and the Southern Regional University Center of the Autonomous University of Chapingo (UACh).

Over the next

Over the next

One of the 10 stories in the book shows how the

One of the 10 stories in the book shows how the