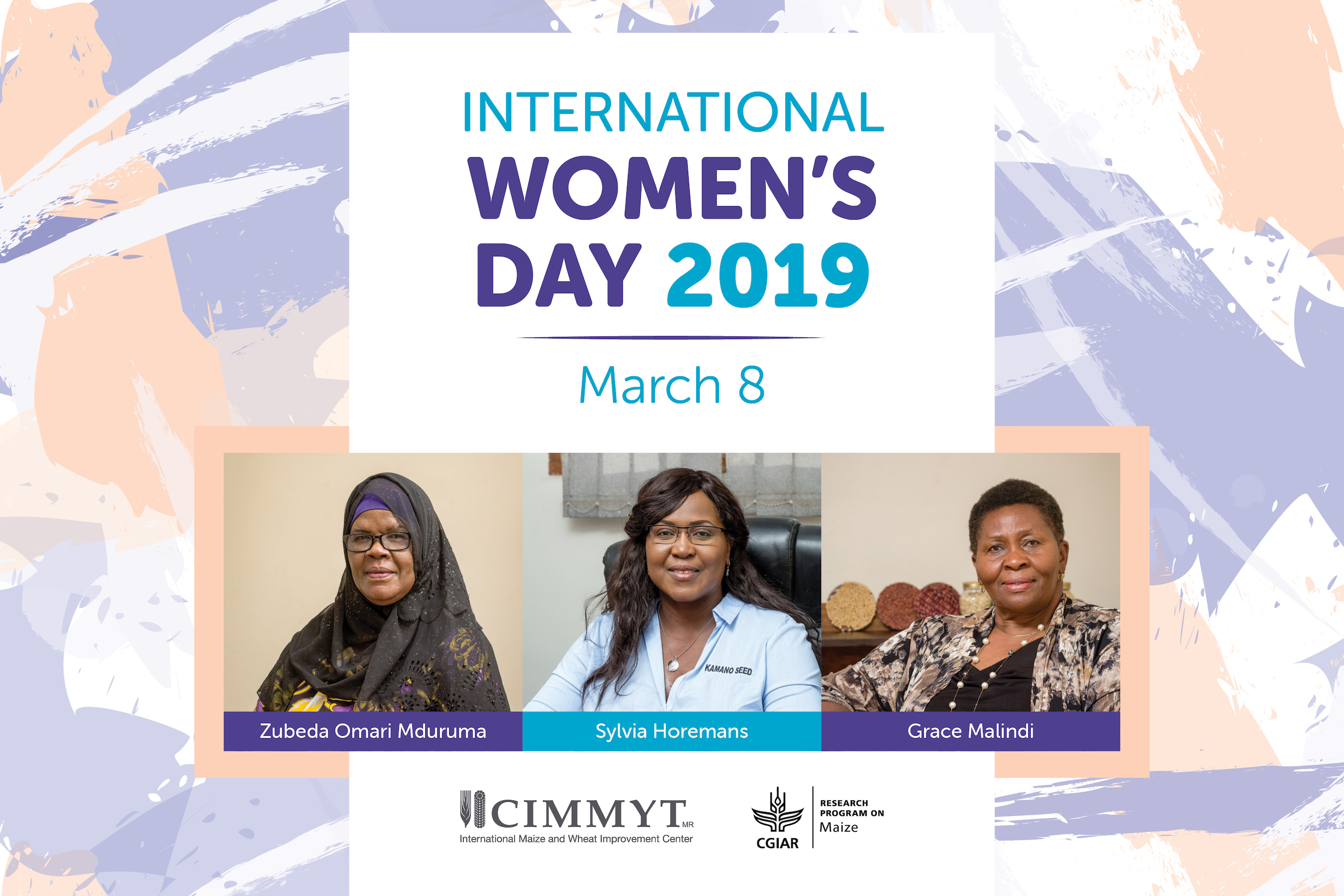

International Women’s Day 2019: Women in seed systems in Africa

The maize seed sector in eastern and southern Africa is male-dominated. Most seed companies operating in the region are owned and run by men. Access to land and financial capital can often be a constraint for women who are keen on investing in agriculture and agribusiness. However, there are women working in this sector, breaking social barriers, making a contribution to improving household nutrition and livelihoods by providing jobs and improved seed varieties.

The Gender team within the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center’s (CIMMYT) Socioeconomics Program conducted interviews with women owners of seed companies in eastern and southern Africa. They shared information on their background, their motivation to start their businesses, what sets their companies apart from the competition, the innovative approaches they use to ensure smallholder farmers adopt improved seed varieties, the unique challenges they face as women in the seed sector and the potential for growth of their companies. The resulting stories will be published as a report in May 2019.

These women in leading roles serve as mentors and examples to both male and female employees. In honor of International Women’s Day, held March 8, 2019, CIMMYT would like to share some of their stories to recognize these women — and many others like them — and the important work they do in seed systems in Africa.

Sylvia Horemans

Sylvia Horemans started Kamano Seeds in April 2004 together with her late husband Desire Horemans. The company derives its name from a stream that runs through their farm in Mwinilinga, Zambia. Kamano means a stream that never dries, aptly describing the growth the company has enjoyed over the years, enabling it to capture 15 percent of the country’s seed market share. Sylvia became the company’s Chief Executive Officer in 2016.

“The initial business was only to sell commercial products but we realized there was a high demand for seed so we decided to start our own seed business,” says Sylvia. “We work with cooperatives which identify ideal farmers to participate in seed production.”

The company takes pride in the growth they have witnessed in their contract workers. “Most farmers we started with [now] have 20 to 40 hectares. Some are businessmen and have opened agrodealer shops where they sell agricultural inputs,” Sylvia announced.

Kamano prides itself in improving the lives of women smallholders and involving women in decision-making structures. “We empower a lot of women in agriculture through our out-grower scheme,” says Sylvia. She makes a deliberate effort to recruit women farmers, ensuring they receive payment for their seeds. “We pay the women who did the work and not their husbands.”

To read the full story, please click here.

Zubeda Mduruma

Zubeda Mduruma, 65, is a plant breeder. She took to agriculture from a young age, as she enjoyed helping her parents in the family farm. After high school, Zubeda obtained a bachelor’s degree in Agriculture. Then she joined Tanzania’s national agriculture research system, working at the Ilonga Agricultural Research Institute (ARI-Ilonga) station. She then pursued her master’s in Plant Breeding and Biometry from Cornell University in the United Stations and obtained a doctorate in Plant Breeding at Sokoine University of Agriculture in Tanzania, while working and raising her family. “I wanted to be in research, so I could breed materials which would be superior than what farmers were using, because they were getting very low yields,” says Zubeda. In the 22 years she was at Ilonga, Zubeda was able to release 15 varieties.

Aminata Quality Seeds is a family business that was registered in 2008, owned by Zubeda, her husband and their four daughters. Aminata entered the seed market as an out-grower, producing seed for local companies for two years. The company started its own seed production in 2010, and the following year it was marketing improved varieties. “I decided to start a company along the Coast and impart my knowledge on improved technologies, so farmers can get quality crops for increased incomes,” says Zubeda.

Zubeda encourages more women to venture into the seed business. “To do any business, you have to have guts. It is not the money; it is the interest. When you have the interest, you will always look for ways on how to start your seed business.”

To read the full story, please click here.

Grace Malindi

Grace Malindi, 67, started Mgom’mera in Malawi in 2014 with her sister Florence Kahumbe, who had experience in running agrodealer shops. Florence was key in setting up the business, particularly through engagement with agro-dealers, while Grace’s background in extension was valuable in understanding their market. Grace has a doctoral degree in Human and Community Development with a double minor in Gender and International Development and Agriculture Extension and Advisory from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in the United States. Mgom’mera is a family-owned enterprise. Grace’s three children are involved in the business, serving as directors.

Mgom’mera distinguishes itself from other seed companies because of its focus on maize varieties that have additional nutritive value. The company uses the tagline “Creating seed demand from the table to the soil.” It educates farmers not only on how to plant the seed they sell, but also on how to prepare nutritious dishes with their harvest. The company stocks ZM623, a drought-tolerant open-pollinated variety, and Chitedze 2, a quality protein maize. In the 2019 maize season it will also sell MH39, a pro-vitamin A variety. In addition, they are looking forward to beginning quality protein maize hybrid production in the near future, having started the process of acquiring materials from CIMMYT.

Grace observes that women entrepreneurs are late entrants in seed business. “You need agility, flexibility and experience to run a seed business and with time you will improve,” says Grace, advising women who may be interested in venturing into this male-dominated business.

To read the full story, please click here.