Sowing seeds of change to champion Conservation Agriculture

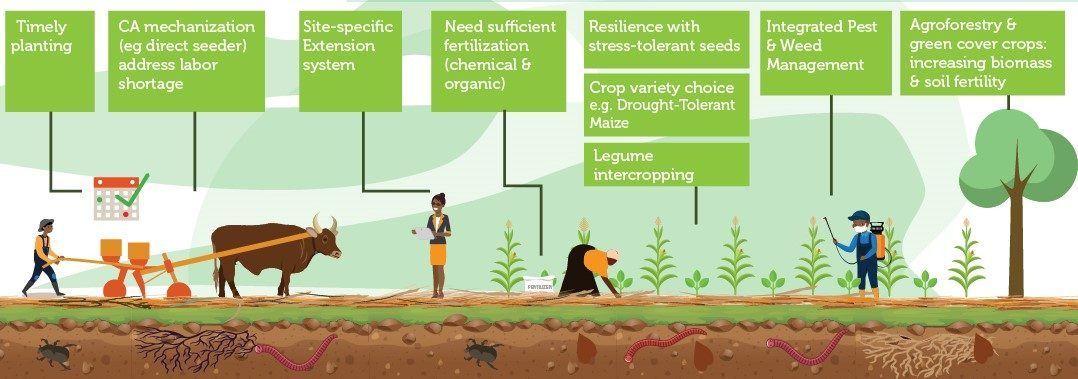

Florence Mutize’s thriving fields of maize, in Bindura, a small town in Mashonaland Central region of Zimbabwe, serve as living proof of the successes of Conservation Agriculture (CA), a sustainable cropping system that helps reverse soil degradation, augment soil health, increase crop yields, and reduce labor requirements while helping farmers adapt to climate change. The seeds of her hard work are paying off, empowering her family through education and ensuring that a nutritious meal is always within reach.

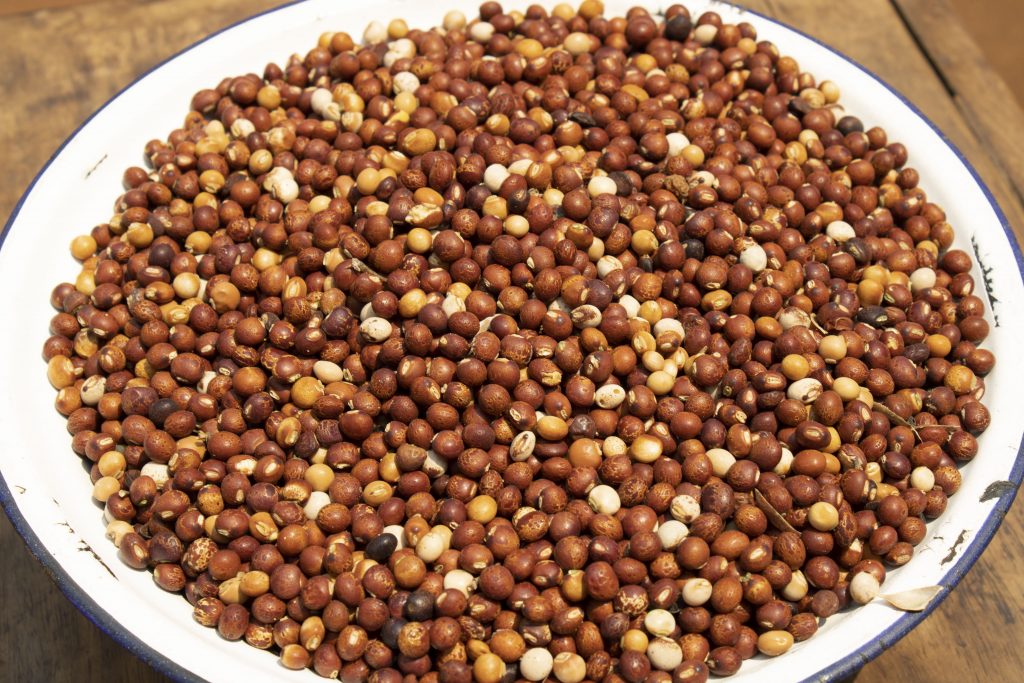

“I have been dedicated to these CA trials since 2004, starting on a small plot,” said Mutize. “Now, with years of experience and adaptation to changing climates, I’ve seen my yields increase significantly, harvesting up to a tonne of maize on a 30 by 30m plot using direct seeding and ripping techniques together with crop residue to cover the soil and rotating maize with soybean.”

Mutize is one of many mother trial host farmers implementing CA principles through the CGIAR Ukama Ustawi regional initiative in Bindura. A mother trial is a research approach involving testing and validating a suite of climate-smart agriculture technologies to identify the best-performing ones which can then be adopted on a larger scale.

Nestled in the Mazowe valley, Bindura experiences a subtropical climate characterized by hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters, ideal for agricultural production. But the extremes of the changing climate, like imminent dry spells and El Niño-induced threats, are endangering local farmers. Yet, smallholder farmers like Mutize have weathered the extremes and continued conducting mother trials, supported by the agriculture extension officers of the Agricultural and Rural Development Advisory Services (ARDAS) Department of the Ministry of Lands, Agriculture, Fisheries, Water and Rural Development.

“Where I once harvested only five bags of maize, rotating maize with soybeans now yields 40 bags of maize and 10 bags of soybeans,” Mutize proudly shares.

The UU-supported CA program also extends to farmers in Shamva, like Elphas Chinyanga, another mother trial implementer since 2004.

“From experimenting with various fertilization methods to introducing mechanized options like ripping and direct seeding, these trials have continuously evolved,” said Chinyanga. “Learning from past experiences, we have gotten much more benefits and we have incorporated these practices into other fields beyond the trial area. I am leaving this legacy to my children to follow through and reap the rewards.”

Learning has been a crucial element in the dissemination of CA technologies, with CIMMYT implementing refresher training together with ARDAS officers to ensure that farmers continue to learn CA principles. As learning is a progressive cycle, it is important to package knowledge in a way that fits into current training and capacity development processes.

This process could also be labelled as “scaling deep” as it encourages farmers to move away from conventional agriculture technologies. Reciprocally, scientists have been learning from the experiences of farmers on the ground to understand what works and what needs improvement.

Inspired by the successes of his peers in Shamva, Hendrixious Zvomarima joined the program as a host farmer and saw a significant increase in yields and efficiency on his land.

“For three years, I have devoted time to learn and practice what other farmers like Elphas Chinyanga were practicing. It has been 14 years since joining, and this has been the best decision I have made as it has improved my yields while boosting my family’s food basket,” said Zvomarima.

The longevity and success of the initiative can be attributed to committed farmers like Mutize, Chinyanga, and Zvomarima, who have been part of the program since 2004 and are still executing the trials. Farmer commitment, progressive learning, and cultivating team spirit have been the success factors in implementing these trials. CIMMYT’s long-term advocacy and learning from the farmers has been key to a more sustainable, resilient, and empowered farming community.

Climate mitigation or resilience?

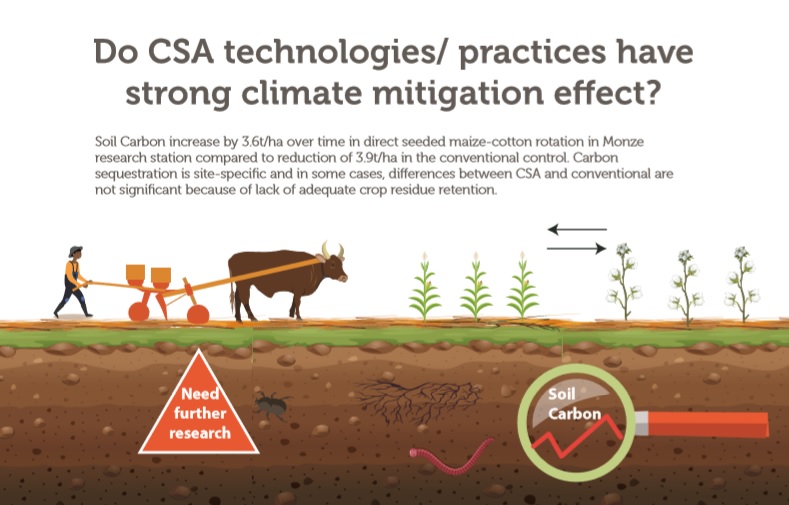

Climate mitigation or resilience?  “Science is important to build up solid evidence of the benefits of a healthy soil and push forward much-needed policy interventions to incentivize soil conservation,” Thierfelder states.

“Science is important to build up solid evidence of the benefits of a healthy soil and push forward much-needed policy interventions to incentivize soil conservation,” Thierfelder states.

A

A