When a devastating stripe rust epidemic hit Ethiopia last year, newly-released wheat varieties derived from international partnerships proved resistant to the disease, and are now being multiplied for seed.

Wheat farmers and breeders are embroiled in a constant arms race against the rust diseases, as new rust races evolve to conquer previously resistant varieties. Ethiopia’s wheat crop became the latest casualty when a severe stripe rust epidemic struck in 2010. “The dominant wheat varieties were hit by this disease, and in some of the cases where fungicide application was not done there was extremely high yield loss,” says Firdissa Eticha, national wheat research program coordinator with the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR). “This is a threat for the future because there is climate change—which has already been experienced in Ethiopia—and the varieties which we have at hand were totally hit by this stripe rust.”

Ethiopia is not alone; stripe rust has become a serious problem across Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, with epidemics in 2009 and 2010 which many countries have struggled to control. What’s new is the evolution of stripe rust races that are able to overcome Yr27, a major rust resistance gene that many important wheat varieties rely on. Although recent weather conditions have allowed the new rust races to thrive, they first began to emerge more than a decade ago, and CIMMYT’s wheat program, always looking forward to the next threat, began selection for resistance to Yr27-virulent races in 1998.

“CIMMYT has a number of wheat lines that have shown good-to-excellent resistance to stripe rust without relying on Yr27, in screening in Mexico, Ecuador, and Kenya,” says Ravi Singh, CIMMYT distinguished scientist and rust expert who leads the breeding effort in Mexico. Many of these are also resistant to the stem rust race Ug99 and have 10-15% higher yields than currently-grown varieties, according to Singh. The current step is to work with national programs to identify and promote the most useful of the resistant materials for their environments—a process that was underway in Ethiopia when the epidemic struck.

Eticha is leading his country’s fight against stripe rust. Reflecting on the disease, he says: “For me it is as important as stem rust. I find it like a wildfire when there is a susceptible variety. You see very beautiful fields actually, yellow like a canola field in flower. But for farmers it is a very sad sight. Stripe rust can cause up to 100% yield loss.” There is no official figure yet on the overall loss to Ethiopia’s wheat harvest for 2010, but it is expected to be more than 20%.

Stripe rust symptoms in the field in Ethiopia. | Photo: Firdissa Eticha

The other common name for stripe rust is yellow rust. Severely-infected plants look bright yellow, due to a photosynthesis-blocking coating of spores of the fungus Puccinia striiformis, which causes the disease. These spores are yellow to orange-yellow in color, and form pustules. These usually appear as narrow stripes along the leaves, and can cover the leaves in susceptible varieties, as well as affecting the leaf sheaths and the spikes. The disease lowers both yield and grain quality, causing stunted and weakened plants, fewer spikes, fewer grains per spike, and shriveled grains with reduced weight.

Epidemic flourishes with damp weather

Normally, Ethiopia has two distinct rainy seasons, one short and one main, allowing for two wheat cropping cycles per year. However, 2010 saw persistent gentle rains throughout the year, with prolonged dews and cool temperatures—perfect weather for stripe rust. Most wheat varieties planted in Ethiopia were susceptible, including the two most popular, Kubsa and Galema, so damage was severe. Under normal conditions, the disease only attacks high-altitude wheat in Ethiopia, but last year it was rampant even at low altitudes. This could reflect the appearance of a new race that is less temperature sensitive, or simply the unusual weather conditions; Ethiopian researchers are currently waiting for the results of a rust race analysis.

There was little Ethiopia could do to prevent the epidemic; imported fungicides controlled the disease where they were applied on time, but supplies were limited and expensive. Newly-released, resistant varieties provide a way out of danger. In particular, two CIMMYT lines released in Ethiopia in 2010 proved resistant to stripe rust in their target environments: Picaflor#1, which was released in Ethiopia as Kakaba, and Danphe#1, released as Danda’a. Picaflor#1 is targeted to environments where Kubsa is grown, and so has the potential to replace it, and Danphe#1 could similarly replace Galema. Both varieties are also high-yielding and resistant to Ug99.

CIMMYT scientists Hans-Joachim Braun (left) and Bekele Abeyo visit the fields of the Kulumsa Research Station where CIMMYT materials resistant to stripe rust are being multiplied for seed supply to Ethiopian farmers.

Seed multiplication of resistant CIMMYT varieties

As soon as the situation became clear, EIAR and the Ethiopian Seed Enterprise (the state-owned organization responsible for multiplication and distribution of improved seed of all major crops in Ethiopia) worked together to speed the multiplication of seed of these varieties, using irrigation during the dry seasons. This is happening now, with almost 500 hectares under multiplication over the winter—421 of Picaflor#1 and 70 of Danphe#1. Financial support from this project came from the USAID Famine Fund. Two resistant lines from the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) were released in Ethiopia in 2011, and will add to the diversity for resistance.

Eticha does not foresee any difficulty encouraging farmers to adopt the new varieties. In 2010 they were grown by 900 farmers on small on-farm demonstration plots, as part of EIAR’s routine annual program, so they have been seen—free of stripe rust—by thousands of farmers, and there will be more demonstration plots as more seed becomes available. However, “farmers are at risk still even if the varieties are there,” he says, “the problem is seed supply.” Some seed will reach farmers this year, but the priority will be ongoing multiplication to build up availability as fast as possible.

Hans-Joachim Braun, director of CIMMYT’s Global Wheat Program, visited Ethiopia in 2010. “The epidemic was a real wake-up call,” he says. “Researchers have known for more than ten years that the varieties grown are susceptible. Farmers are not aware of the danger, so it is the responsibility of researchers and seed producers, if we know a variety is susceptible, to replace it with something better.”

|

Exploring rust solutions in Syria

The ongoing fight against the wheat rust diseases is an international, collaborative effort involving many partners in national programs and international organizations. CIMMYT works closely with ICARDA, which leads efforts against the wheat rust diseases in Central and West Asia and North Africa. At the International Wheat Stripe Rust Symposium, organized by ICARDA in Aleppo, Syria, during 18-20 April 2011, global experts developed strategies to prevent future rust outbreaks and to ensure the control and reduction of rust diseases in the long term.

Other participating organizations included CIMMYT, the Borlaug Global Rust Initiative (BGRI), the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) of the UN, the International Development Research Center (IDRC, Canada), and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). More than 100 scientists from 31 countries presented work and shared ideas on wheat rust surveillance and monitoring, development and promotion of rust-resistant wheat varieties, and crop diversity strategies to slow the progress of rust outbreaks.

CIMMYT was represented by Hans-Joachim Braun and Ravi Singh. “Wheat crops and stripe rust like exactly the same conditions,” says Braun, “and they both love nitrogen. This means that where a farmer has a high yield potential, stripe rust takes it away, if the wheat variety is susceptible. In addition to the really devastating epidemics, the disease is very important because even in bumper years, farmers who grow susceptible varieties still can’t get a good yield.”

One thing all the attendees agreed on was the immediacy of the rust threat. New variants of both stem rust (also known as black rust) and stripe rust (or yellow rust), able to overcome the resistance of popular wheat varieties, are thriving under the more variable conditions caused by climate change, increasing their chances of spreading rapidly. Breeders in turn are quickly developing the varieties farmers need, with durable resistance to stem and stripe rust, as well as improved yield performance, drought tolerance, and regional suitability.

Other major areas of focus are the development of systems for monitoring and surveillance of rust to enable rapid response to initial outbreaks, and overcoming bottlenecks in getting resistant seed quickly to farmers. There is much to be done, but Singh is confident: “If donors, including national programs and the private sector, are willing to invest in wheat research and seed production, we can achieve significant results in a short time.”

|

|

“Ethiopian scientists responded quickly to the epidemic”, says Braun, “but there were heavy losses in 2010. What we need is better communications between scientists, seed producers, and decision makers to ensure the quick replacement of varieties.”

Building on a strong partnership

The value of the collaboration between CIMMYT and Ethiopia is already immeasurable for both partners. CIMMYT materials are routinely screened for rust at Meraro station, an Ethiopian hotspot, in increasing numbers as rust diseases have returned to the spotlight in recent years. CIMMYT lines are also a crucial input for Ethiopia’s national program.

“The contribution of CIMMYT is immense for us,” says Eticha. “CIMMYT provides us with a wide range of germplasm that is almost finished technology—one can say ready materials, that can be evaluated and released as varieties that can be used by farming communities.” Ethiopia has favorable agro-environments for wheat production, and the bread wheat area is expanding because of its high yields compared to indigenous tetraploid wheats. “Wheat is the third most important cereal crop in Ethiopia,” explains Eticha, “and it is really very important in transforming Ethiopia’s economy.”

Bekele Abeyo, CIMMYT senior scientist and wheat breeder based in Ethiopia, works closely with the national program. CIMMYT helps in many ways, he explains, for example with training and capacity building, as well as donation of materials, including computers, vehicles, and even chemicals for research. “In addition, we assign scientists to work closely with the national program, and facilitate germplasm exchange, providing high-yielding, disease resistant, widely-adapted varieties.” Speaking of the stripe rust epidemic, he says, “last year, the Ethiopian government spent more than USD 3.2 million just to buy fungicides, so imagine, the use of resistant varieties can save a lot of money. Most farmers are not able to buy these expensive fungicides. During the epidemic, fungicides were selling for three to four times their normal price, so you can see the value of resistant varieties.”

“I think East Africa is colonized by rust. Unless national programs work hard to overcome and contain disease pressure, wheat production is under great threat,” says Abeyo. “It is very important that we continue to strengthen the national programs to overcome the rust problem in the region.” With Yr27-virulent stripe rust races now widespread throughout the world, Ethiopia’s story has echoes in many CIMMYT partner countries. The challenge is to work quickly together to identify and replace susceptible varieties with the new, productive, resistant materials.

For more information: Bekele Abeyo, senior scientist and wheat breeder (b.abeyo@cgiar.org)

Faizal Ahmad and his brother Hayatt Mohammad are sharecroppers on this 8 hectare parcel of land. They pay the landowner a share and the crew that is harvesting gets a share, and with what is left, they try to feed their families, maybe sell a little.

Faizal Ahmad and his brother Hayatt Mohammad are sharecroppers on this 8 hectare parcel of land. They pay the landowner a share and the crew that is harvesting gets a share, and with what is left, they try to feed their families, maybe sell a little. At least three more varieties developed from materials originally from CIMMYT (some via the winter wheat breeding program in Turkey) are in the new varietal release pipeline that Afghanistan has implemented. They have already demonstrated in farmers’ fields that they are well-suited to local conditions and can provide more wheat per hectare than farmers currently harvest with yields in on-farm trials of almost 5 tons per hectare, double what most farmers get. These wheats can be seen in trials at the Dehdadi Research Farm near Mazur, almost within sight of the sharecropping brothers.

At least three more varieties developed from materials originally from CIMMYT (some via the winter wheat breeding program in Turkey) are in the new varietal release pipeline that Afghanistan has implemented. They have already demonstrated in farmers’ fields that they are well-suited to local conditions and can provide more wheat per hectare than farmers currently harvest with yields in on-farm trials of almost 5 tons per hectare, double what most farmers get. These wheats can be seen in trials at the Dehdadi Research Farm near Mazur, almost within sight of the sharecropping brothers. CIMMYT has entered into a collaborative research program to increase household and regional food security and incomes, as well as economic development, in eastern and southern Africa, through improved productivity from more resilient and sustainable maize-legume farming systems. Known as “Sustainable intensification of maize-legume cropping systems for food security in eastern and southern Africa” (SIMLESA), the program aims to increase productivity by 30% and reduce downside risk by 30% within a decade for at least 0.5 million farm households in those countries, with spill-over benefits throughout the region. In addition to CIMMYT, the program involves the

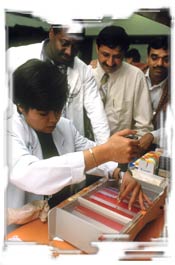

CIMMYT has entered into a collaborative research program to increase household and regional food security and incomes, as well as economic development, in eastern and southern Africa, through improved productivity from more resilient and sustainable maize-legume farming systems. Known as “Sustainable intensification of maize-legume cropping systems for food security in eastern and southern Africa” (SIMLESA), the program aims to increase productivity by 30% and reduce downside risk by 30% within a decade for at least 0.5 million farm households in those countries, with spill-over benefits throughout the region. In addition to CIMMYT, the program involves the At an agricultural research station in Kenya, ingenuity, improvised tools, and a small group of talented, dedicated researchers and technicians using good science, are on the front line of the battle to prevent a potential multi-billion dollar crop disaster for the world.

At an agricultural research station in Kenya, ingenuity, improvised tools, and a small group of talented, dedicated researchers and technicians using good science, are on the front line of the battle to prevent a potential multi-billion dollar crop disaster for the world.

More than two decades of joint efforts between researchers from Nepal and CIMMYT have helped boost the country’s maize yields 36% and those of wheat by 85%, according to a report compiled to mark the 25th anniversary of the partnership. As a result, farmers even in the country’s remote, mid hill mountain areas have more food and brighter futures.

More than two decades of joint efforts between researchers from Nepal and CIMMYT have helped boost the country’s maize yields 36% and those of wheat by 85%, according to a report compiled to mark the 25th anniversary of the partnership. As a result, farmers even in the country’s remote, mid hill mountain areas have more food and brighter futures.

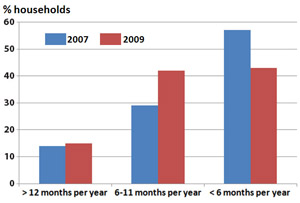

During 1997-2008,

During 1997-2008, Maize Transforms Landscapes and Livelihoods in Bangladesh

Maize Transforms Landscapes and Livelihoods in Bangladesh

A USAID-funded study by Rutgers economist Carl Pray concludes that present and future impacts of the Asian Maize Biotechnology Network (AMBIONET)—a forum that during 1998-2005 fostered the use of biotechnology to boost maize yields in Asia’s developing countries—should produce benefits that far exceed its cost.

A USAID-funded study by Rutgers economist Carl Pray concludes that present and future impacts of the Asian Maize Biotechnology Network (AMBIONET)—a forum that during 1998-2005 fostered the use of biotechnology to boost maize yields in Asia’s developing countries—should produce benefits that far exceed its cost. A USAID-funded study by Williams College economist Douglas Gollin shows that modern maize and wheat varieties not only increase maximum yields in developing countries, but add hundreds of millions of dollars each year to farmers’ incomes by guaranteeing more reliable yields than traditional varieties.

A USAID-funded study by Williams College economist Douglas Gollin shows that modern maize and wheat varieties not only increase maximum yields in developing countries, but add hundreds of millions of dollars each year to farmers’ incomes by guaranteeing more reliable yields than traditional varieties.

Speaking at the SIMLESA’s second “birthday party,” Joana Hewitt, chairperson of the ACIAR Commission for International Agricultural Research, reiterated the Australian government’s commitment to long-term partnerships with African governments. Participants also heard of the new SIMLESA Program in Zimbabwe, focusing on crop-livestock interactions. During the dinner, Kenya and Mozambique were recognized for their efforts in promoting and strengthening local innovation platforms.

Speaking at the SIMLESA’s second “birthday party,” Joana Hewitt, chairperson of the ACIAR Commission for International Agricultural Research, reiterated the Australian government’s commitment to long-term partnerships with African governments. Participants also heard of the new SIMLESA Program in Zimbabwe, focusing on crop-livestock interactions. During the dinner, Kenya and Mozambique were recognized for their efforts in promoting and strengthening local innovation platforms.

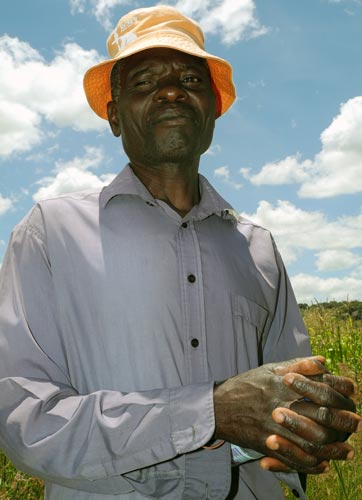

Tunga Silvar grows maize to feed his wife and fourgrandchildren on about 0.5 hectares of land in Mawanga, Zimbabwe, a hilly area some 45 kilometers northeast of Harare. Like otherfarmers in the region, he is acutely aware of the value of nitrogen fertilizer, continually juggles his limited household financesto get it, and is poorer and hungrier when he can’t. “We used to sell maize, but in the last five years we haven’t been able to do so,” saysSilvar. “I had to pay school fees for my grandchildren, so I couldn’t buy fertilizer. Fertilizer is very important, especially in our type of soil. If you don’t apply it, youcan barely harvest anything.”

Tunga Silvar grows maize to feed his wife and fourgrandchildren on about 0.5 hectares of land in Mawanga, Zimbabwe, a hilly area some 45 kilometers northeast of Harare. Like otherfarmers in the region, he is acutely aware of the value of nitrogen fertilizer, continually juggles his limited household financesto get it, and is poorer and hungrier when he can’t. “We used to sell maize, but in the last five years we haven’t been able to do so,” saysSilvar. “I had to pay school fees for my grandchildren, so I couldn’t buy fertilizer. Fertilizer is very important, especially in our type of soil. If you don’t apply it, youcan barely harvest anything.”

Late and erratic rainfall in Zimbabwe has many farmers facing the prospect of poor harvests. The current hardships from drought though may furnish some hopefor farmers. New drought tolerant varieties are being tested in on-farm trials under farmer management. Many of the trials are experiencing drought stress—aperfect opportunity to identify the best varieties for such harsh conditions. A recent visit to on-farm trials in the Murewa District of Zimbabwe showed many new drought tolerant products performing well. Local farmer Sailas Ruswa is growing a trial and was enthusiastic about what he saw: some varieties showedsigns of severe drought stress, but a few were holding up well and were expected to produce good yields.

Late and erratic rainfall in Zimbabwe has many farmers facing the prospect of poor harvests. The current hardships from drought though may furnish some hopefor farmers. New drought tolerant varieties are being tested in on-farm trials under farmer management. Many of the trials are experiencing drought stress—aperfect opportunity to identify the best varieties for such harsh conditions. A recent visit to on-farm trials in the Murewa District of Zimbabwe showed many new drought tolerant products performing well. Local farmer Sailas Ruswa is growing a trial and was enthusiastic about what he saw: some varieties showedsigns of severe drought stress, but a few were holding up well and were expected to produce good yields.