Bottlenecks between basic and applied plant science jeopardize life-saving crop improvements

For a number of reasons, including limited interdisciplinary collaboration and a dearth of funding, revolutionary new plant research findings are not being used to improve crops.

“Translational research” — efforts to convert basic research knowledge about plants into practical applications in crop improvement — represents a necessary link between the world of fundamental discovery and farmers’ fields. This kind of research is often seen as more complicated and time consuming than basic research and less sexy than working at the “cutting edge” where research is typically divorced from agricultural realities in order to achieve faster and cleaner results; however, modern tools — such as genomics, marker-assisted breeding, high throughput phenotyping of crop traits using drones, and speed breeding techniques — are making it both faster and cost-effective.

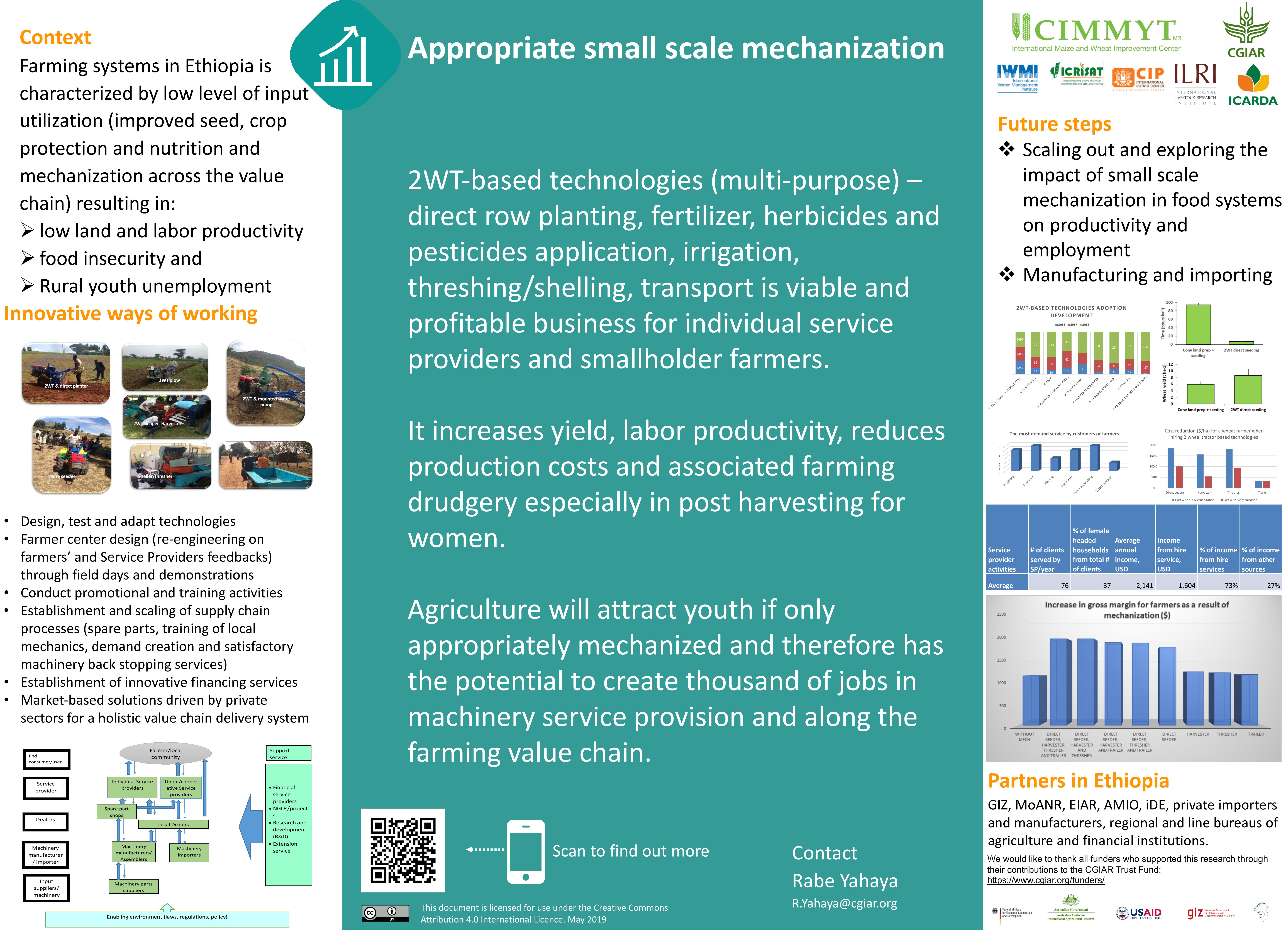

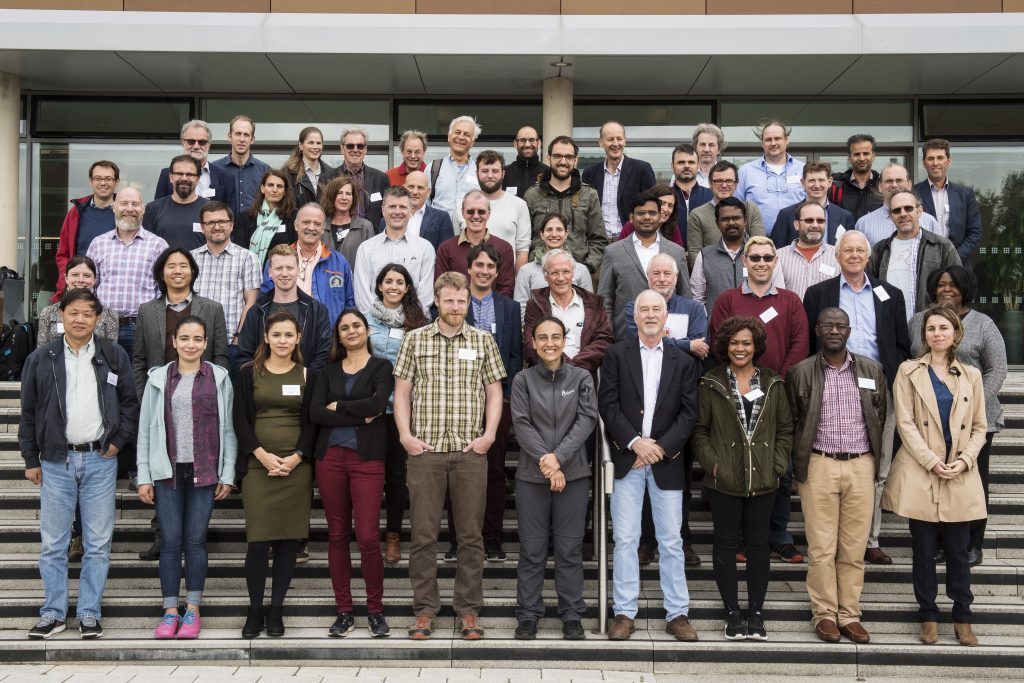

In a new article in Crop Breeding, Genetics, and Genomics, wheat physiologist Matthew Reynolds of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and co-authors make the case for increasing not only funding for translational research, but the underlying prerequisites: international and interdisciplinary collaboration towards focused objectives and a visionary approach by funding organizations.

“It’s ironic,” said Reynolds. “Many breeding programs have invested in the exact technologies — such as phenomics, genomics and informatics — that can be powerful tools for translational research to make real improvements in yield and adaptation to climate, disease and pest stresses. But funding to integrate these tools in front-line breeding is quite scarce, so they aren’t reaching their potential value for crop improvement.”

Many research findings are tested for their implications for wheat improvement by the International Wheat Yield Partnership (IWYP) at the IWYP Hub, a centralized technical platform for evaluating innovations and building them into elite wheat varieties, co-managed by CIMMYT at its experimental station in Obregon, Mexico.

IWYP has its roots with the CGIAR Research Program on Wheat (WHEAT), which in 2010 formalized the need to boost both wheat yield potential as well as its adaptation to heat and drought stress. The network specializes in translational research, harnessing scientific findings from around the world to boost genetic gains in wheat, and capitalizing on the research and pre-breeding outputs of WHEAT and the testing networks of the International Wheat Improvement Network (IWIN). These efforts also led to the establishment of the Heat and Drought Wheat Improvement Consortium (HeDWIC).

“We’ve made extraordinary advances in understanding the genetic basis of important traits,“ said IWYP’s Richard Flavell, a co-author of the article. “But if they aren’t translated into crop production, their societal value is lost.”

The authors, all of whom have proven track records in both science and practical crop improvement, offer examples where exactly this combination of factors led to the impactful application of innovative research findings.

- Improving the Vitamin A content of maize: A variety of maize with high Vitamin A content has the potential to reduce a deficiency that can cause blindness and a compromised immune system. This development happened as a result of many translational research efforts, including marker-assisted selection for a favorable allele, using DNA extracted from seed of numerous segregating breeding crosses prior to planting, and even findings from gerbil, piglet and chicken models — as well as long-term, community-based, placebo-controlled trials with children — that helped establish that Vitamin A maize is bioavailable and bioefficacious.

- Flood-tolerant rice: Weather variability due to climate change effects is predicted to include both droughts and floods. Developing rice varieties that can withstand submergence in water due to flooding is an important outcome of translational research which has resulted in important gains for rice agriculture. In this case, the genetic trait for flood tolerance was recognized, but it took a long time to incorporate the trait into elite germplasm breeding programs. In fact, the development of flooding tolerant rice based on a specific SUB 1A allele took over 50 years at the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines (1960–2010), together with expert molecular analyses by others. The translation program to achieve efficient incorporation into elite high yielding cultivars also required detailed research using molecular marker technologies that were not available at the time when trait introgression started.

Other successes include new approaches for improving the yield potential of spring wheat and the discovery of traits that increase the climate resilience of maize and sorghum.

One way researchers apply academic research to field impact is through phenotyping. Involving the use of cutting edge technologies and tools to measure detailed and hard to recognize plant traits, this area of research has undergone a revolution in the past decade, thanks to more affordable digital measuring tools such as cameras and sensors and more powerful and accessible computing power and accessibility.

Scientists are now able to identify at a detailed scale plant traits that show how efficiently a plant is using the sun’s radiation for growth, how deep its roots are growing to collect water, and more — helping breeders select the best lines to cross and develop.

Phenotyping is key to understanding the physiological and genetic bases of plant growth and adaptation and has wide application in crop improvement programs. Recording trait data through sophisticated non-invasive imaging, spectroscopy, image analysis, robotics, high-performance computing facilities and phenomics databases allows scientists to collect information about traits such as plant development, architecture, plant photosynthesis, growth or biomass productivity from hundreds to thousands of plants in a single day. This revolution was the subject of discussion at a 2016 gathering of more than 200 participants at the International Plant Phenotyping Symposium hosted by CIMMYT in Mexico and documented in a special issue of Plant Science.

There is currently an explosion in plant science. Scientists have uncovered the genetic basis of many traits, identified genetic markers to track them and developed ways to measure them in breeding programs. But most of these new findings and ideas have yet to be tested and used in breeding programs, wasting their potentially enormous societal value.

Establishing systems for generating and testing new hypotheses in agriculturally relevant systems must become a priority, Reynolds states in the article. However, for success, this will require interdisciplinary, and often international, collaboration to enable established breeding programs to retool. Most importantly, scientists and funding organizations alike must factor in the long-term benefits as well as the risks of not taking timely action. Translating a research finding into an improved crop that can save lives takes time and commitment. With these two prerequisites, basic plant research can and should positively impact food security.

Authors would like to acknowledge the following funding organizations for their commitment to translational research.

The International Wheat Yield Partnership (IWYP) is supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) in the UK; the U. S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in the USA; and the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture (SFSA) in Switzerland.

The Heat and Drought Wheat Improvement Consortium (HeDWIC) is supported by the Sustainable Modernization of Traditional Agriculture (MasAgro) Project by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (SADER) of the Government of Mexico; previous projects that underpinned HeDWIC were supported by Australia’s Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC).

The Queensland Government’s Department of Agriculture and Fisheries in collaboration with The Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC) have provided long-term investment for the public sector sorghum pre-breeding program in Australia, including research on the stay-green trait. More recently, this translational research has been led by the Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation (QAAFI) within The University of Queensland.

ASI validation work and ASI translation and extension components with support from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, respectively.

Financial support for the maize proVA work was partially provided by HarvestPlus (www.HarvestPlus.org), a global alliance of agriculture and nutrition research institutions working to increase the micronutrient density of staple food crops through biofortification. The CGIAR Research Program MAIZE (CRP-MAIZE) also supported this research.

The CGIAR Research Program on Wheat (WHEAT) is led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), with the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) as a primary research partner. Funding comes from CGIAR, national governments, foundations, development banks and other agencies, including the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR), the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).