Scientists convene in Kenya for intensive wheat disease training

An international cohort of scientists representing 12 countries gathered at the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) station in Njoro for a comprehensive training course aimed at honing their expertise in wheat rust pathology.

The two-week program “Enhancing Wheat Disease Early Warning Systems, Germplasm Evaluation, Selection, and Tools for Improving Wheat Breeding Pipelines,” was a collaborative effort between CIMMYT and Cornell University and supported by the Wheat Disease Early Warning Advisory System (DEWAS) and Accelerating Genetic Gains in Maize and Wheat projects.

With a mission to bolster the capabilities of National Agricultural Research Systems (NARS), the training course attracted more than 30 participants from diverse corners of the globe.

Maricelis Acevedo, a research professor of global development at Cornell and the associate director of Wheat DEWAS, underscored the initiative’s significance. “This is all about training a new generation of scientists to be at the forefront of efforts to prevent wheat pathogens epidemics and increase food security all over the globe,” Acevedo said.

First initiated in 2008 through the Borlaug Global Rust Initiative, these training programs in Kenya have played a vital role in equipping scientists worldwide with the most up-to-date knowledge on rust pathogens. The initial twelve training sessions received support from the BGRI under the auspices of the Durable Rust Resistance in Wheat and Delivering Genetic Gain in Wheat projects.

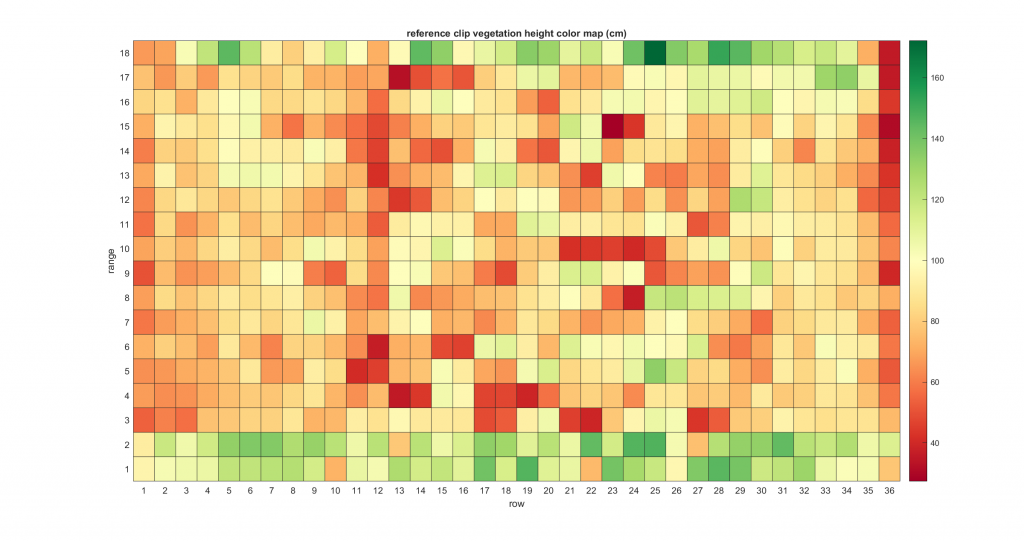

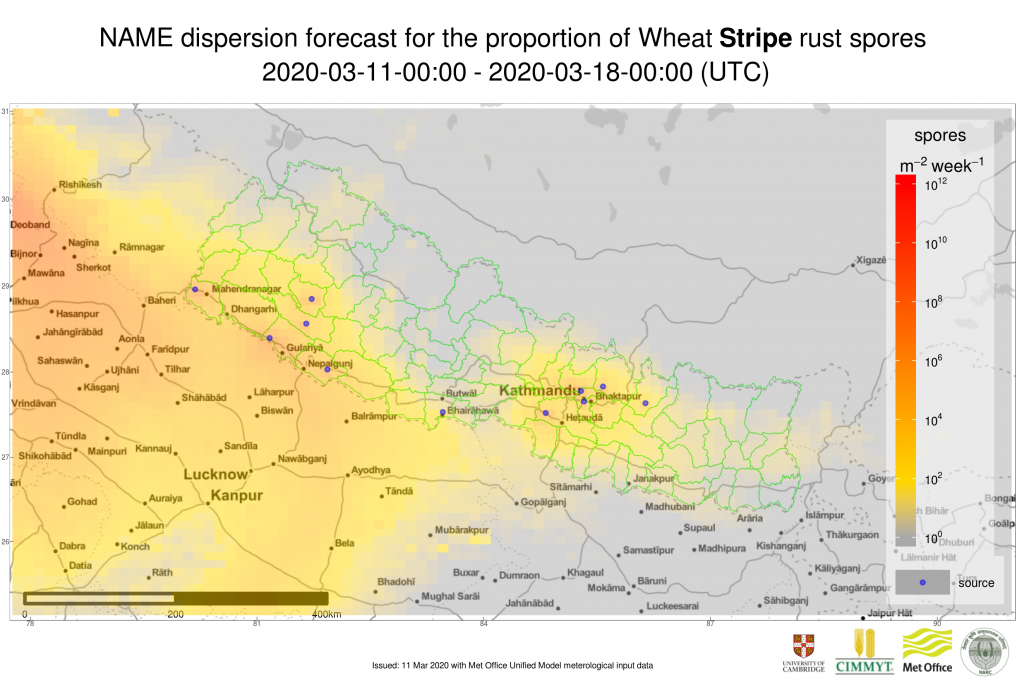

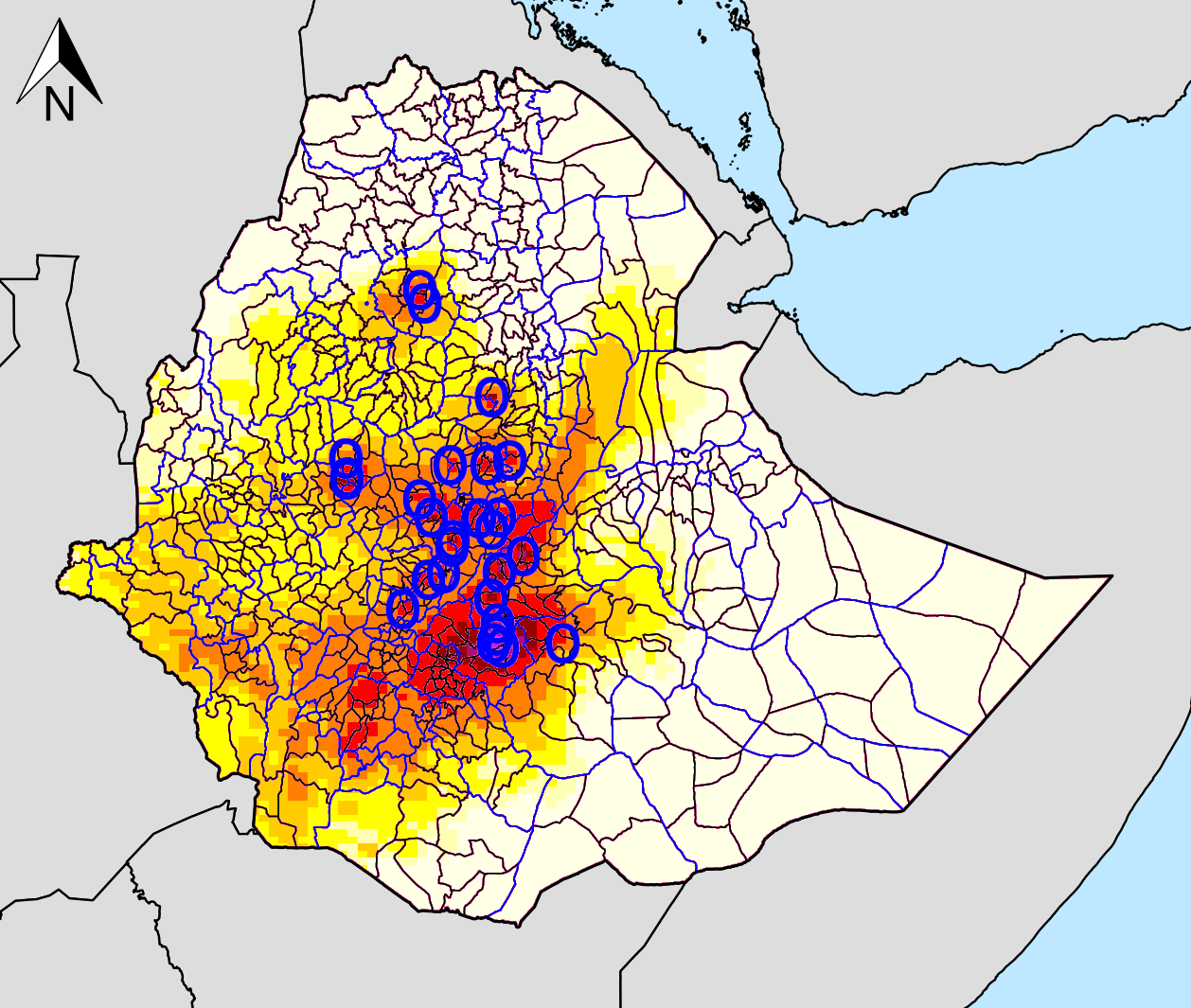

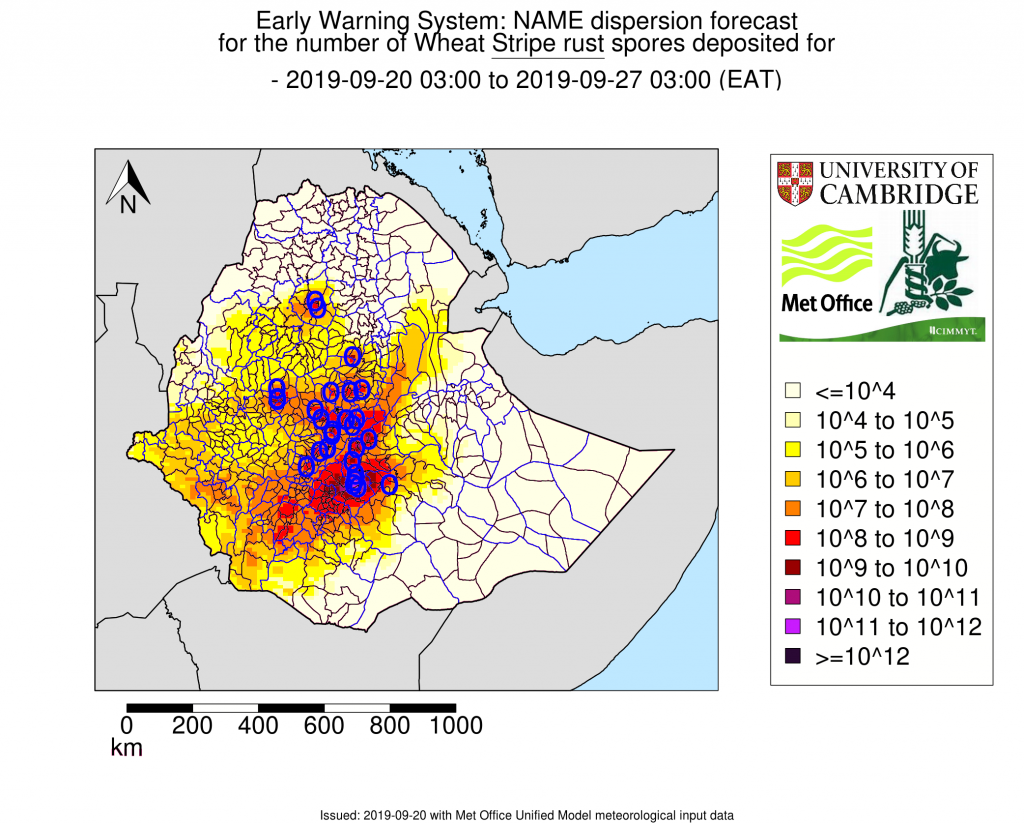

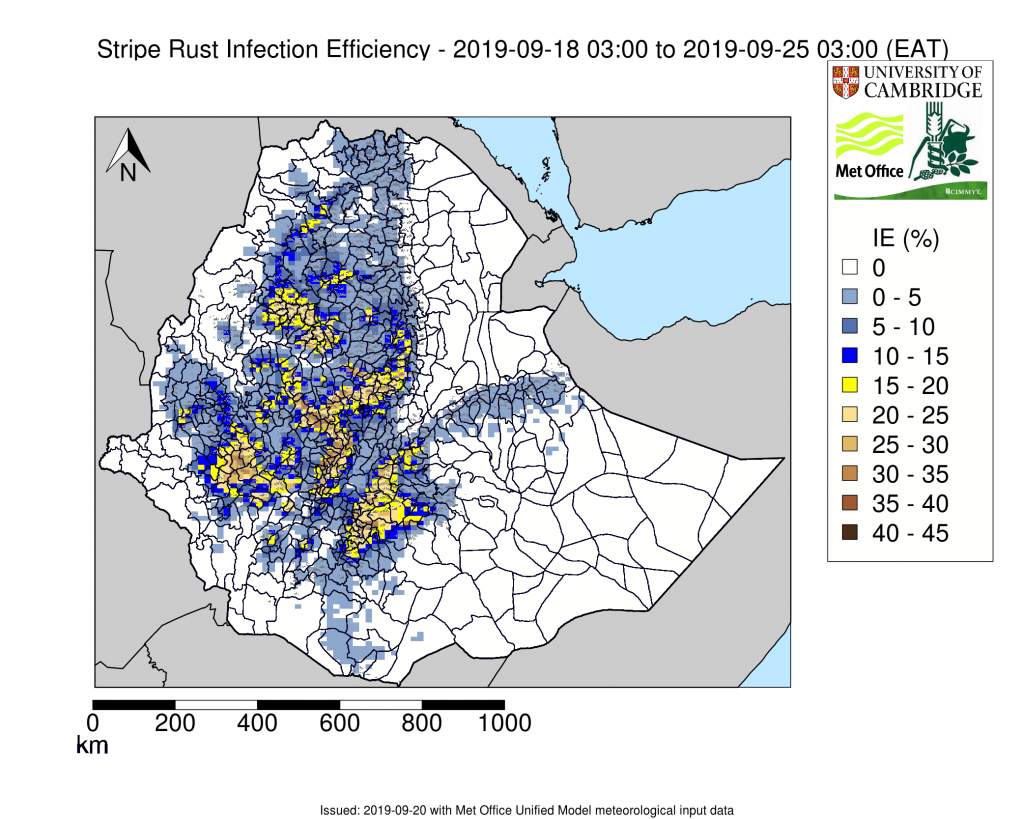

This year’s training aims to prepare global scientists to protect against disease outbreaks that threaten wheat productivity in East Africa and South Asia. The course encompassed a wide array of practical exercises and theoretical sessions designed to enhance the participants’ knowledge in pathogen surveillance, diagnostics, modeling, data management, early warning assessments, and open science publishing. Presentations were made by DEWAS partners from the John Innes Centre, Aarhus University, the University of Cambridge and University of Minnesota.

The course provided practical, hands-on experience in selecting and evaluating wheat breeding germplasm, race analysis and greenhouse screening experiments to enhance knowledge of rust diseases, according to Sridhar Bhavani, training coordinator for the course.

“This comprehensive training program encompasses diverse aspects of wheat research, including disease monitoring, data management, epidemiological models, and rapid diagnostics to establish a scalable and sustainable early warning system for critical wheat diseases such as rusts, fusarium, and wheat blast,” said Bhavani, wheat improvement lead for East Africa at CIMMYT and head of wheat rust pathology and molecular genetic in CIMMYT’s Global Wheat program.

An integral part of the program, Acevedo said, was the hands-on training on wheat pathogen survey and sample collection at KALRO. The scientists utilized the international wheat screening facility at KALRO as a training ground for hot-spot screening for rust diseases resistance.

Daisy Kwamboka, an associate researcher at PlantVillage in Kenya, said the program provided younger scientists with essential knowledge and mentoring.

“I found the practical sessions particularly fascinating, and I can now confidently perform inoculations and rust scoring on my own,” said Kwamboka said, who added that she also learned how to organize experimental designs and the basics of R language for data analysis.

DEWAS research leaders Dave Hodson, Bhavani and Acevedo conducted workshops and presentations along with leading wheat rust experts. Presenters included Robert Park and Davinder Singh from the University of Sydney; Diane Sauders from the John Innes Centre; Clay Sneller from Ohio State University; Pablo Olivera from the University of Minnesota; Cyrus Kimani, Zennah Kosgey and Godwin Macharia from KALRO; Leo Crespo, Susanne Dreisigacker, Keith Gardner, Velu Govindan, Itria Ibba, Arun Joshi, Naeela Qureshi, Pawan Kumar Singh and Paolo Vitale from CIMMYT; Chris Gilligan and Jake Smith from the University of Cambridge; and Jens Grønbech Hansen and Mogens S. Hovmøller from the Global Rust Reference Center at Aarhus University.

“I thoroughly enjoyed the knowledge imparted by the invited experts, along with the incredible care they have shown us throughout this wonderful training.”

Narain Dhar, Borlaug Institute for South Asia

For participants, the course offered a crucial platform for international collaboration, a strong commitment to knowledge sharing, and its significant contribution to global food security.

“The dedication of the trainers truly brought the training to life, making it incredibly understandable,” said Narain Dhar, research fellow at the Borlaug Institute for South Asia.

The event not only facilitated learning but also fostered connections among scientists from different parts of the world. These newfound connections hold the promise of sparking innovative collaborations and research endeavors that could further advance the field of wheat pathology.