Remembering Max Alcalá, who led CIMMYT’s wheat international nurseries

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) sadly notes the passing of Maximino Alcalá de Stefano, former head of the center’s Wheat International Nurseries service, on August 27. He was 80 years old.

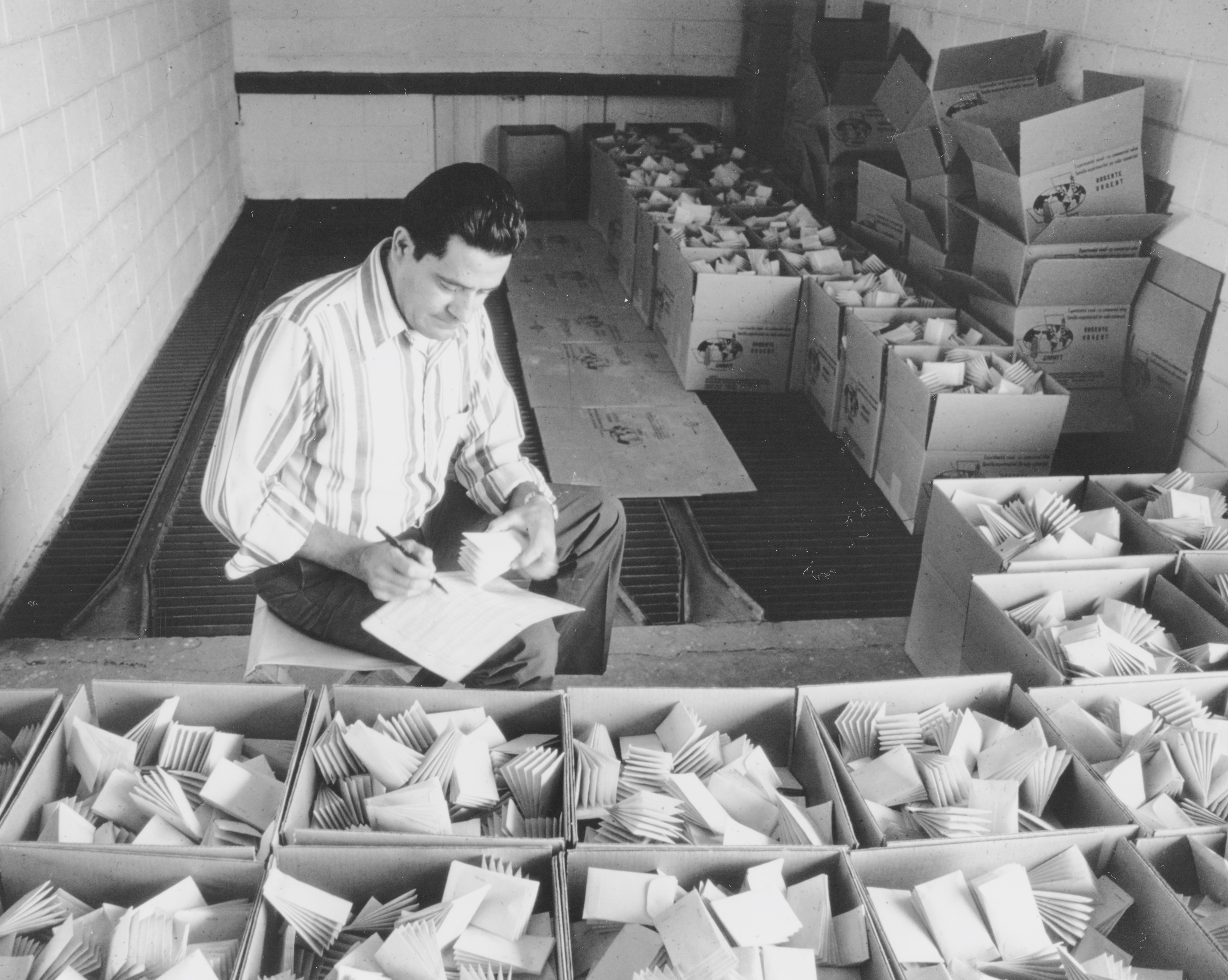

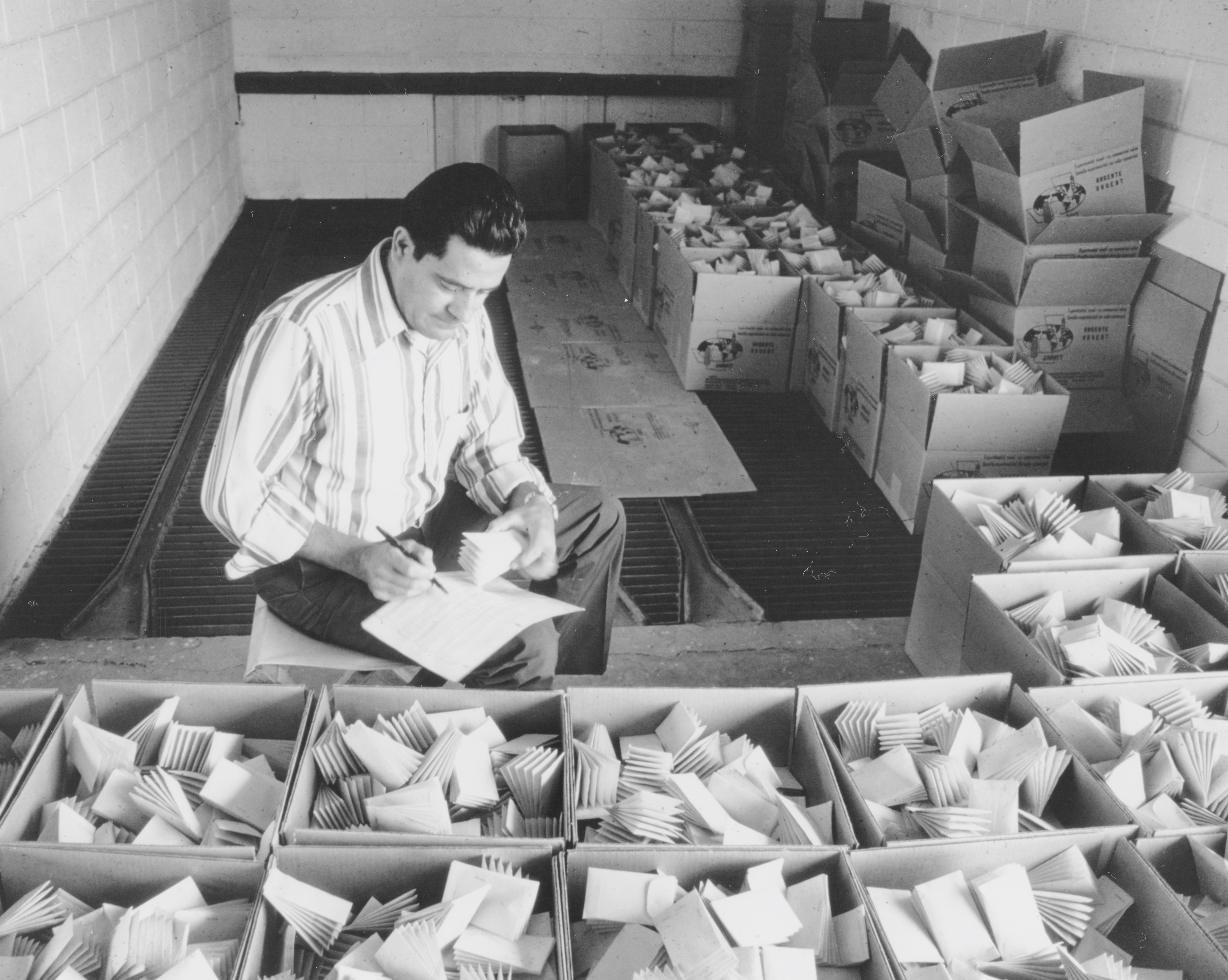

Fondly known as “Max” by friends and colleagues, Alcalá worked at CIMMYT from 1967 to 1992, coordinating wheat international nurseries during the late 1960s and early 1970s. The job included organizing nursery shipments to over 100 partners worldwide each year and collating, analyzing, and sharing results from the nurseries grown.

The printed international nursery report featured an introductory section that described the nurseries, the locations, the statistical analyses used, and an overview of the performance of the breeding lines tested, which comprised the best CIMMYT materials but also germplasm from other sources. The report also carried tables with full data from each location as well as summary tables.

“Max was instrumental in preparing and distributing the printed nursery results, now made available online but which continue to provide crucial input for breeding by CIMMYT and partners,” said Hans-Joachim Braun, director of CIMMYT’s Global Wheat Program. “He also helped start the international nursery database.”

A native of Mexico, Alcalá completed a bachelor’s in Science at the Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro in 1964 and a master’s at Texas A&M University in 1967. Alcalá pursued doctoral studies in wheat breeding at Oregon State University under the guidance of renowned OSU researcher Warren E. Kronstad, finishing in 1974.

His professional experience prior to CIMMYT included appointments at Mexico’s National Institute of Agricultural Research (INIA) and in the national extension services.

Later in his career, Alcalá supported wheat training at CIMMYT and helped coordinate visitors services at CIMMYT’s experimental station near Ciudad Obregón, in Mexico’s Sonora state.

The CIMMYT community sends its deepest sympathies and wishes for peace to the Alcalá family.

Nearly 140 members of the CIMMYT community and valued Mexican partners gathered on 16 April 2013 with the family of Gregorio “Goyo” Martínez Valdés, retired CIMMYT institutional relations officer who succumbed to cancer at 77 on 07 April, in a solemn ceremony in the pine grove at El Batán to commemorate his life and work.

Nearly 140 members of the CIMMYT community and valued Mexican partners gathered on 16 April 2013 with the family of Gregorio “Goyo” Martínez Valdés, retired CIMMYT institutional relations officer who succumbed to cancer at 77 on 07 April, in a solemn ceremony in the pine grove at El Batán to commemorate his life and work. “He had a big heart, divided into clear portions, and CIMMYT occupied a big chunk,” said Martínez’s son Francisco, who noted his father’s supreme love for work and colleagues. He also brought a portion of his father’s ashes and bequeathed them to CIMMYT.

“He had a big heart, divided into clear portions, and CIMMYT occupied a big chunk,” said Martínez’s son Francisco, who noted his father’s supreme love for work and colleagues. He also brought a portion of his father’s ashes and bequeathed them to CIMMYT.