A view from above

Scientists at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) have been harnessing the power of drones and other remote sensing tools to accelerate crop improvement, monitor harmful crop pests and diseases, and automate the detection of land boundaries for farmers.

A crucial step in crop improvement is phenotyping, which traditionally involves breeders walking through plots and visually assessing each plant for desired traits. However, ground-based measurements can be time-consuming and labor-intensive.

This is where remote sensing comes in. By analyzing imagery taken using tools like drones, scientists can quickly and accurately assess small crop plots from large trials, making crop improvement more scalable and cost-effective. These plant traits assessed at plot trials can also be scaled out to farmers’ fields using satellite imagery data and integrated into decision support systems for scientists, farmers and decision-makers.

Here are some of the latest developments from our team of remote sensing experts.

Measuring plant height with high-powered drones

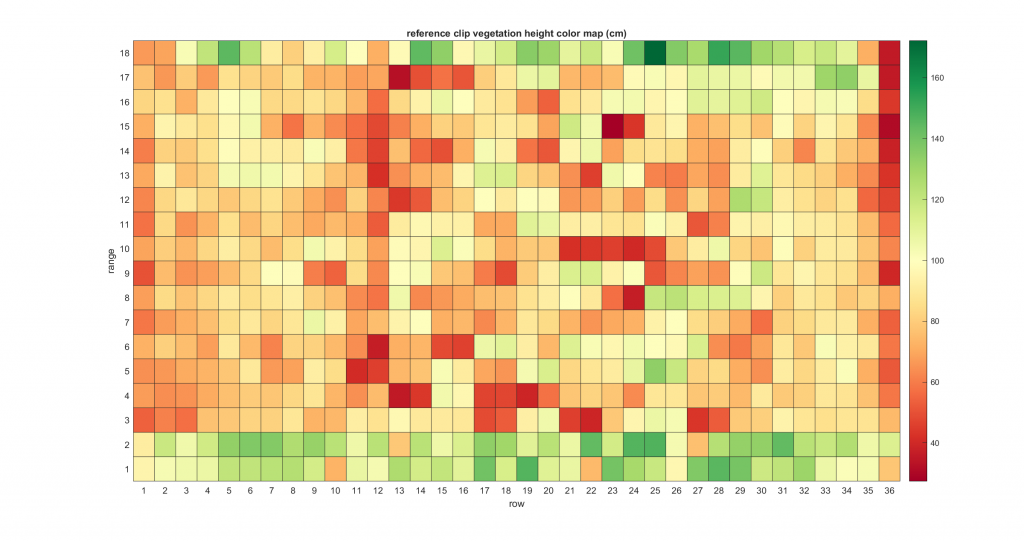

A recent study, published in Frontiers in Plant Science validated the use of drones to estimate the plant height of wheat crops at different growth stages.

The research team, which included scientists from CIMMYT, the Federal University of Viçosa and KWS Momont Recherche, measured and compared wheat crops at four growth stages using ground-based measurements and drone-based estimates.

The team found that plant height estimates from drones were similar in accuracy to measurements made from the ground. They also found that by using drones with real-time kinematic (RTK) systems onboard, users could eliminate the need for ground control points, increasing the drones’ mapping capability.

Recent work on maize has shown that drone-based plant height assessment is also accurate enough to be used in maize improvement and results are expected to be published next year.

Advancing assessment of pests and diseases

CIMMYT scientists and their research partners have advanced the assessment of Tar Spot Complex — a major maize disease found in Central and South America — and Maize Streak Virus (MSV) disease, found in sub-Saharan Africa, using drone-based imaging approach. By analyzing drone imagery, scientists can make more objective disease severity assessments and accelerate the development of improved, disease-resistant maize varieties. Digital imaging has also shown great potential for evaluating damage to maize cobs by fall armyworm.

Scientists have had similar success with other common foliar wheat diseases, Septoria and Spot Blotch with remote sensing experiments undertaken at experimental stations across Mexico. The results of these experiments will be published later this year. Meanwhile, in collaboration with the Federal University of Technology, based in Parana, Brazil, CIMMYT scientists have been testing deep learning algorithms — computer algorithms that adjust to, or “learn” from new data and perform better over time — to automate the assessment of leaf disease severity. While still in the experimental stages, the technology is showing promising results so far.

Improving forecasts for crop disease early warning systems

CIMMYT scientists, in collaboration with Université catholique de Louvain (UCLouvain), Cambridge University and the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR), are currently exploring remote sensing solutions to improve forecast models used in early warning systems for wheat rusts. Wheat rusts are fungal diseases that can destroy healthy wheat plants in just a few weeks, causing devastating losses to farmers.

Early detection is crucial to combatting disease epidemics and CIMMYT researchers and partners have been working to develop a world-leading wheat rust forecasting service for a national early warning system in Ethiopia. The forecasting service predicts the potential occurrence of the airborne disease and the environmental suitability for the disease, however the susceptibility of the host plant to the disease is currently not provided.

CIMMYT remote sensing experts are now testing the use of drones and high-resolution satellite imagery to detect wheat rusts and monitor the progression of the disease in both controlled field trial experiments and in farmers’ fields. The researchers have collaborated with the expert remote sensing lab at UCLouvain, Belgium, to explore the capability of using European Space Agency satellite data for mapping crop type distributions in Ethiopia. The results will be also published later this year.

Delivering expert irrigation and sowing advice to farmers phones

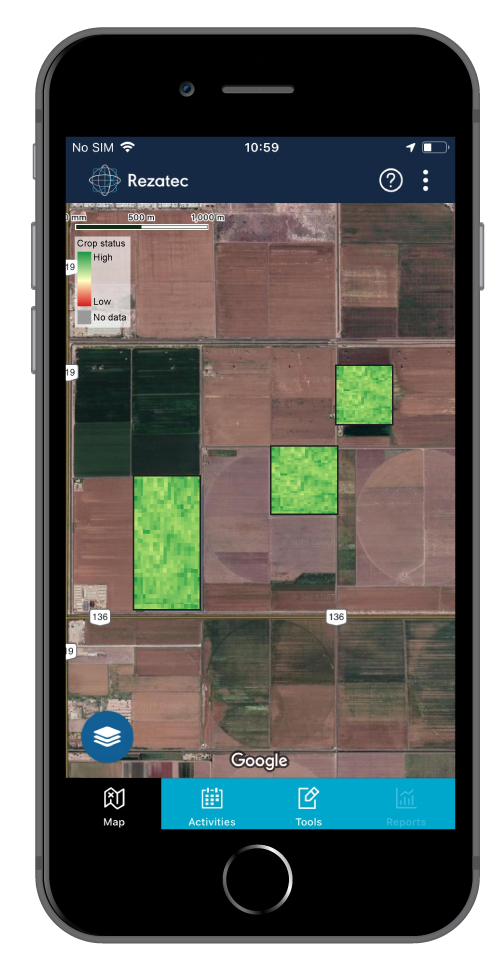

Through an initiative funded by the UK Space Agency, CIMMYT scientists and partners have integrated crop models with satellite and in-situ field data to deliver valuable irrigation scheduling information and optimum sowing dates direct to farmers in northern Mexico through a smartphone app called COMPASS — already available to iOS and Android systems. The app also allows farmers to record their own crop management activities and check their fields with weekly NDVI images.

The project has now ended, with the team delivering a webinar to farmers last October to demonstrate the app and its features. Another webinar is planned for October 2021, aiming to engage wheat and maize farmers based in the Yaqui Valley in Mexico.

Detecting field boundaries using high-resolution satellite imagery

In Bangladesh, CIMMYT scientists have collaborated with the University of Buffalo, USA, to explore how high-resolution satellite imagery can be used to automatically create field boundaries.

Many low and middle-income countries around the world don’t have an official land administration or cadastre system. This makes it difficult for farmers to obtain affordable credit to buy farm supplies because they have no land titles to use as collateral. Another issue is that without knowing the exact size of their fields, farmers may not be applying to the right amount of fertilizer to their land.

Using state of the art machine learning algorithms, researchers from CIMMYT and the University of Buffalo were able to detect the boundaries of agricultural fields based on high-resolution satellite images. The study, published last year, was conducted in the delta region of Bangladesh where the average field size is only about 0.1 hectare.

Developing climate-resilient wheat

CIMMYT’s wheat physiology team has been evaluating, validating and implementing remote sensing platforms for high-throughput phenotyping of physiological traits ranging from canopy temperature to chlorophyll content (a plant’s greenness) for over a decade. Put simply, high-throughput phenotyping involves phenotyping a large number of genotypes or plots quickly and accurately.

Recently, the team has engaged in the Heat and Drought Wheat Improvement Consortium (HeDWIC) to implement new high-throughput phenotyping approaches that can assist in the identification and evaluation of new adaptive traits in wheat for heat and drought.

The team has also been collaborating with the Accelerating Genetic Gains in Maize and Wheat (AGG) project, providing remote sensing data to improve genomic selection models.

Cover photo: An unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV drone) in flight over CIMMYT’s experimental research station in Ciudad Obregon, Mexico. (Photo: Alfredo Saenz/CIMMYT)