The long-running Drought Tolerant Maize for Africa (DTMA) Project started in 2007 and ends this month. What next after this long-distance runner, and, more importantly, what will happen to DTMA products?

Enter DTMASS, which stands for Drought Tolerant Maize for Africa Seed Scaling. It’s to be a seamless transition to the next stage on the research-to-development continuum, albeit with a switch in terms of who takes the lead and is firmly in the front seat, and who plays a facilitating role and now settles in the back seat.

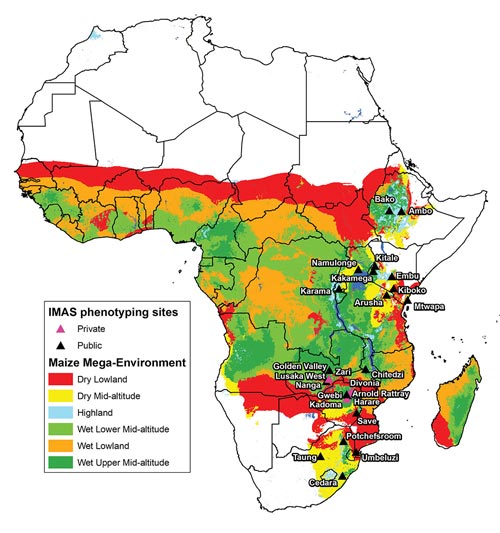

DTMASS stands on the shoulders of DTMA ‒ and other projects ‒ the fundamental difference being that now seed companies will be the main drivers of the project. In essence, this is in fact the rationale for DTMASS. Also, to avoid duplication, the geographical areas DTMASS shall concentrate on are different from DTMA sites.

FIGURES: The DTMA scorecard in 2014

- 13: the number of countries covered in Africa

- 72: the percentage these 13 countries which jointly account for, as a proportion of all maize grown in sub-Saharan Africa

- 205: the cumulative number of maize varieties released (mostly hybrids)

- 184: the distinct varieties represented by the 205 varieties above

FACTS

- 49%: the additional yield from hybrids, on average, compared to open pollinated varieties

- Going up: popularity of hybrids in Africa

“We’ve noted the good products that come from DTMA, and we are keen to forge partnerships to take these products further down the research-to-development path and make a difference,” said Dr. John McMurdy, International Research Advisor at the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), which is funding DTMASS.

DTMASS was launched at continental level late last year in November 2014 (see page 1 here), followed by focused country-level launches in each of the participating countries. Implementation began in March 2015.

Continuing conundrum on women and men: let’s talk business Studies show that gender gaps continue to persist, from seed access to seed production. Therefore, a gender-responsive approach is core to DTMASS’ work, recognizing that gender-responsiveness is not a single silver bullet. Rather, it is an accumulation of small efforts done at each of the five steps of seed access and production which will lead to gender-equitable outcomes. The facilitative five steps are (1) seed production (2) processing and branding (3) promotion, (4) distribution and network, and (5) monitoring and evaluation).

“These gender-equitable outcomes are not a work of charity,” stressed Vongai Kandiwa, CIMMYT’s Gender Specialist. “It makes business sense. Seed companies are losing business opportunities by failing to target a large sector of the market – women.”

And while men not only own most of the land but are also twice as likely to walk into an agrodealer shop (observation research in Eastern Kenya), anecdotal evidence as well as sample – but representative – research has shown that men generally consult their wives first before purchasing. Their wives will not help them make informed decisions if they themselves are not aware of the options available.

The curious puzzle of Kenya’s paradox, and some shocks for locals During the launch of DTMASS in Kenya on 2nd February 2015, it was revealed that maize productivity in Kenya has been on a debilitating downward spiral. Yet Kenya has bona fide and well-established seed companies with significant knowledge and experience. While productivity in the 1980s was well over two tonnes per hectare, it has since dipped to 1.6 tonnes, even as Kenya’s potential production stands at an impressive and life-changing 10 tonnes.

“Good partnerships would turn around that situation, and there’s every reason why Kenya should do better,” observed Dr. Tsedeke Abate, DTMASS Project Leader, who also leads DTMA.

The DTMASS goal for Kenya is 1,600 tonnes of certified seed by 2019. CIMMYT will work in partnership with the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) and local seed companies, whose representatives attended the meeting. Some of the seed-company representatives said they were shocked by Kenya’s dismal performance on production: they said they knew it was low, but had not known it was that low.

Dr. Joyce Malinga, Acting Director of KALRO’s Food Crops Research Institute, observed that seed has the greatest potential to increase on-farm production and enhance productivity. She said KALRO is keen on commercialization of released drought-tolerant varieties, as a means to ensure that these varieties reach farmers.

The Kenya launch in Nairobi was preceded by country launches in Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia. DTMASS encourages cross-country learning, and the experience from the Kenya launch would be taken to Uganda the following week, in the same manner Kenya had benefitted from lessons for the three preceding country launches.

Uganda: countering counterfeits, the heat is on, and onwards and upwards! “This project is at the right place at the right time,” said Dr Imelda Kashaija, Deputy Director, National Agricultural Research Organisation (NARO), Uganda, on 4th February 2015. She was speaking at the launch of the DTMASS Project in Kampala.

She observed that in Uganda, formal players offering certified seed currently account for a mere 35 percent of the market, leaving 65 percent to informal players. This is an untenable situation, inherent with many problems with the spread of disease as the biggest risk (see maize lethal necrosis, for example). It is estimated that nearly half (40 percent) of the hybrid seed sold in Uganda is fake. “We all know that if we don’t improve the formal seed system, we continue to encourage the bad habit of counterfeit seed that is rampant in Uganda. One way to reduce counterfeit is to strengthen the formal system so farmers get good-quality seed,” Dr. Kashaija added.

Poor pickings that will lead to a paltry harvest: a maize cob from a crop hard-hit by drought.

Poor pickings that will lead to a paltry harvest: a maize cob from a crop hard-hit by drought.

Photo: A. Wangalachi CIMMYT

She said the project will bring in drought-tolerant maize varieties that will help Uganda fight climate change. In the 19th century, Uganda was dubbed ‘the pearl of Africa’ by Victorian-era traveler and journalist, Henry Morton Stanley, for good reason. The country sits astride the broad shores of the world’s second-largest freshwater lake (Victoria) which drains into the mighty River Nile, evoking images of glistening green lush landscapes, water in plenty and banana fronds waving in the tropical breeze. But this postcard-perfect picture is beginning to shatter. “We’re getting more dry than wet days,” revealed Dr. Kashaija. “Distribution of rain has changed, even if not the amount. Not only are there now fewer days of rain, the rains are also now unpredictable. So, crops that take longer in the field have poor harvests.” It is also important to remember eastern Uganda falls firmly in the drylands.

Describing seed companies as “our other arm when reaching communities,” Dr. Kashaija observed that seed companies take the seed NARO produces and use it for business. But they focus on more than money by delivering quality seed, thereby helping the government in its objective to improve formal systems. “Through this project, more farmers are going to be able to access improved drought-tolerant seed,” Dr. Kashaija concluded.

Dr. McMurdy described DTMASS as “a strategic project for USAID. DTMASS is part of a suite of new investments, and part of the Feed the Future initiative. This meeting is an opportunity to discuss constraints, and also to foster partnerships and more cooperation. We are looking for synergies with other stakeholders and efforts, including the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa.”

“We have the knowledge and technology, and what remains is translating knowledge to action,” added Dr. Abate. He said that Uganda has made significant progress in terms of maize productivity, as indicated by the latest FAO statistics.

The acreage devoted to maize has also doubled over the past several years. Through DTMASS, by 2019, Uganda is expected to produce 1,800 tonnes of improved maize. “I have no doubt Uganda can exceed this projection, given the good team, good partnership and experienced players,” Dr. Abate predicted.

A helping hand Capacity-building to help meet project goals is an integral part of DTMASS, starting with ‘servicing the engine’ – the seed companies that will drive DTMASS.

To this end, in-country seed business management and production courses were held for participating companies. First up was Malawi in June 2015, with Uganda, Tanzania and Mozambique in July, Kenya in August, and concluding with Ethiopia in September.

Links:

Participants at the DTMASS project launch in Uganda, 4th February 2015. Photo: CIMMYT

Participants at the DTMASS project launch in Uganda, 4th February 2015. Photo: CIMMYT

Poor pickings that will lead to a paltry harvest: a maize cob from a crop hard-hit by drought.

Poor pickings that will lead to a paltry harvest: a maize cob from a crop hard-hit by drought. Participants at the DTMASS project launch in Uganda, 4th February 2015. Photo: CIMMYT

Participants at the DTMASS project launch in Uganda, 4th February 2015. Photo: CIMMYT

A public-private partnership that, along with CIMMYT, involves national research organizations such as the Kenya Agricultural & Livestock Research Organization (

A public-private partnership that, along with CIMMYT, involves national research organizations such as the Kenya Agricultural & Livestock Research Organization (