funder_partner: India's Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare

Sustainable and Resilient Farming Systems Intensification in the Eastern Gangetic Plains (SRFSI)

The Eastern Gangetic Plains region of Bangladesh, India, and Nepal is home to the greatest concentration of rural poor in the world. This region is projected to be one of the areas most affected by climate change. Local farmers are already experiencing the impact of climate change: erratic monsoon rains, floods and other extreme weather events have affected agricultural production for the past decade. The region’s smallholder farming systems have low productivity, and yields are too variable to provide a solid foundation for food security. Inadequate access to irrigation, credit, inputs and extension systems limit capacity to adapt to climate change or invest in innovation. Furthermore, large-scale migration away from agricultural areas has led to labor shortages and increasing numbers of women in agriculture.

The Sustainable and Resilient Farming Systems Intensification (SRFSI) project aims to reduce poverty in the Eastern Gangetic Plains by making smallholder agriculture more productive, profitable and sustainable while safeguarding the environment and involving women. CIMMYT, project partners and farmers are exploring Conservation Agriculture-based Sustainable Intensification (CASI) and efficient water management as foundations for increasing crop productivity and resilience. Technological changes are being complemented by research into institutional innovations that strengthen adaptive capacity and link farmers to markets and support services, enabling both women and men farmers to adapt and thrive in the face of climate and economic change.

In its current phase, the project team is identifying and closing capacity gaps so that stakeholders can scale CASI practices beyond the project lifespan. Priorities include crop diversification and rotation, reduced tillage using machinery, efficient water management practices, and integrated weed management practices. Women farmers are specifically targeted in the scaling project: it is intended that a third of participants will be women and that at least 25% of the households involved will be led by women.

The 9.7 million Australian dollar (US$7.2 million) SRFSI project is a collaboration between CIMMYT and the project funder, the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research. More than 20 partner organizations include the Departments of Agriculture in the focus countries, the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute, the Indian Council for Agricultural Research, the Nepal Agricultural Research Council, Uttar Banga Krishi Vishwavidyalaya, Bihar Agricultural University, EcoDev Solutions, iDE, Agrevolution, Rangpur-Dinajpur Rural Services, JEEViKA, Sakhi Bihar, DreamWork Solutions, CSIRO and the Universities of Queensland and Western Australia.

OBJECTIVES

- Understand farmer circumstances with respect to cropping systems, natural and economic resources base, livelihood strategies, and capacity to bear risk and undertake technological innovation

- Develop with farmers more productive and sustainable technologies that are resilient to climate risks and profitable for smallholders

- Catalyze, support and evaluate institutional and policy changes that establish an enabling environment for the adoption of high-impact technologies

- Facilitate widespread adoption of sustainable, resilient and more profitable farming systems

Borlaug Institute for South Asia (BISA)

The Borlaug Institute for South Asia (BISA) is a non-profit international research institute dedicated to food, nutrition and livelihood security as well as environmental rehabilitation in South Asia, which is home to more than 300 million undernourished people. BISA is a collaborative effort involving the CIMMYT and the Indian Council for Agricultural Research. The objective of BISA is to harness the latest technology in agriculture to improve farm productivity and sustainably meet the demands of the future. BISA is more than an institute. It is a commitment to the people of South Asia, particularly to the farmers, and a concerted effort to catalyze a second Green Revolution.

BISA was established on October 5, 2011, through an agreement between the Government of India (GoI) and CIMMYT and was bolstered by the globally credible name of Nobel Laureate Norman Ernest Borlaug. The institution draws on the decades of experience and success by CIMMYT, the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), and a global network of partners in using research to generate tangible benefits for farmers internationally. BISA is supported by a growing number of national stakeholders in South Asia. It is committed to stronger collaborations for accelerated impact, most prominently with the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) and the three state governments (Punjab, Bihar, and Madhya Pradesh) where BISA farms are located.

Objectives

- Ensure access to the latest in research and technologies that are currently not available in the region

- Strategize research aimed at doubling food production in South Asia while using less water, land and energy

- Strengthen cutting-edge research that validates and tests new technologies to significantly increase yield potential

- Develop technologies for higher productivity in rice, maize and wheat based farming systems

- Design research outputs targeted to small and marginal farmers across the region

- Build on CIMMYT’s vast germplasm resources, and make research products and know-how developed by BISA freely available to stakeholders

- Create a new generation of scientists to work with new technologies through training programs that will retain them in South Asia

- Enable researchers to pursue multiple strategies and research possibilities while simultaneously allowing for more meaningful collaboration with national institutions

- Build a forum with partners from all sectors – research centers, governments, science community, businesses and farmers – to transform farmers’ lives and improve food security in the region

- Develop a policy environment that embraces new technologies and encourages investments in agricultural research

- Develop and utilize BISA as a regional platform that focuses on agricultural research in the whole of South Asia

Download the BISA Annual Report 2022.

For more information:

Meenakshi Chandiramani

Office Manager

CIMMYT-BISA

m.chandiramani@cgiar.org

Richa Sharma Puri

Communication Specialist

CIMMYT-BISA

r.puri@cgiar.org

Mexican Secretary of Agriculture joins new partners and longtime collaborators in Obregon

“The dream has become a reality.” These words by Victor Manuel Villalobos Arambula, Secretary of Agriculture and Rural Development of Mexico, summed up the sentiment felt among the attendees at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) Global Wheat Program Visitors’ Week in Ciudad Obregon, Sonora.

In support of the contributions to global and local agricultural programs, Villalobos spoke at the week’s field day, or “Dia de Campo,” in front of more than 200 CIMMYT staff and visitors hailing from more than 40 countries on March 20, 2019.

Villalobos recognized the immense work ahead in the realm of food security, but was optimistic that young scientists could carry on the legacy of Norman Borlaug by using the tools and lessons that he left behind. “It is important to multiply our efforts to be able to address and fulfill this tremendous demand on agriculture that we will face in the near future,” he stated.

The annual tour at the Campo Experimental Norman E. Borlaug allows the global wheat community to see new wheat varieties, learn about latest research findings, and hold meetings and discussions to collaborate on future research priorities.

Given the diversity of attendees and CIMMYT’s partnerships, it is no surprise that there were several high-level visits to the field day.

A high-level delegation from India, including Balwinder Singh Sidhu, commissioner of agriculture for the state of Punjab, AK Singh, deputy director general for agricultural extension at the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), and AS Panwar, director of ICAR’s Indian Institute of Farming Systems Research, joined the tour and presentations. All are longtime CIMMYT collaborators on efforts to scale up and disseminate sustainable intensification and climate smart farming practices.

Panwar, who is working with CIMMYT and partners to develop typologies of Indian farming systems to more effectively promote climate smart practices, was particularly interested in the latest progress in biofortification.

“One of the main objectives of farming systems is to meet nutrition of the farming family. And these biofortified varieties can be integrated into farming systems,” he said.

In addition, a delegation from Tunisia, including dignitaries from Tunisia’s National Institute of Field Crops (INGC), signed a memorandum of understanding with CIMMYT officials to promote cooperation in research and development through exchange visits, consultations and joint studies in areas of mutual interest such as the diversification of production systems. INGC, which conducts research and development, training and dissemination of innovation in field crops, is already a strong partner in the CGIAR Research Program on Wheat’s Precision Phenotyping Platform for Wheat Septoria leaf blight.

At the close of the field day, CIMMYT wheat scientist Carolina Rivera was honored as one of the six recipients of the annual Jeanie Borlaug Laube Women in Triticum (WIT) Early Career Award. The award offers professional development opportunities for women working in wheat. “Collectively, these scientists are emerging as leaders across the wheat community,” said Maricelis Acevedo, Associate Director for Science for Cornell University’s Delivering Genetic Gain in Wheat Project, who announced Rivera’s award.

CGIAR Research Program on Wheat and Global Wheat Program Director Hans Braun also took the opportunity to honor and thank three departing CIMMYT wheat scientists. Alexey Morgounov, Carlos Guzman and Mohammad Reza Jalal Kamali received Yaquis, or statues of a Yaqui Indian. The figure of the Yaqui Indian is a Sonoran symbol of beauty and the gifts of the natural world, and the highest recognition given by the Global Wheat Program.

The overarching thread that ran though the Visitor’s Week was that all were in attendance because of their desire to benefit the greater good through wheat science. As retired INIFAP director and Global Wheat Program Yaqui awardee Antonio Gándara said, recalling his parents’ guiding words, “Siempre, si puedes, hacer algo por los demas, porque es la mejor forma de hacer algo por ti. [Always, if you can, do something for others, because it’s the best way to do something for yourself].”

Innovative irrigation promises “more crop per drop” for India’s water-stressed cereals

On World Water day, researchers show how India’s farmers can beat water shortages and grow rice and wheat with 40 percent less water

India’s northwest region is the most important production area for two staple cereals: rice and wheat. But a growing population and demand for food, inefficient flood-based irrigation, and climate change are putting enormous stress on the region’s groundwater supplies. Science has now confronted this challenge: a “breakthrough” study demonstrates how rice and wheat can be grown using 40 percent less water, through an innovative combination of existing irrigation and cropping techniques. The study’s authors, from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), the Borlaug Institute for South Asia (BISA), Punjab Agricultural University and Thapar University, claim farmers can grow similar or better yields than conventional growing methods, and still make a profit.

The researchers tested a range of existing solutions to determine the optimal mix of approaches that will help farmers save water and money. They found that rice and wheat grown using a “sub-surface drip fertigation system” combined with conservation agriculture approaches used at least 40 percent less water and needed 20 percent less Nitrogen-based fertilizer, for the same amount of yields under flood irrigation, and still be cost-effective for farmers. Sub-surface drip fertigation systems involve belowground pipes that deliver precise doses of water and fertilizer directly to the plant’s root zone, avoiding evaporation from the soil. The proposed system can work for both rice and wheat crops without the need to adjust pipes between rotations, saving money and labor. But a transition to more efficient approaches will require new policies and incentives, say the authors.

Read the full story:

Innovative irrigation system could future-proof India’s major cereals. Thomsom Reuters Foundation News, 20 March 2019.

Read the study:

Sidhu HS, Jat ML, Singh Y, Sidhu RK, Gupta N, Singh P, Singh P, Jat HS, Gerard B. 2019. Sub-surface drip fertigation with conservation agriculture in a rice-wheat system: A breakthrough for addressing water and nitrogen use efficiency. Agricultural Water Management. 216:1 (273-283). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2019.02.019

The study received funding from the CGIAR Research Program on Wheat (WHEAT), the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) and the Government of Punjab. The authors acknowledge the contributions of the field staff at BISA and CIMMYT based at Ludhiana, Punjab state.

CIMMYT and UAS-Bangalore to establish a maize doubled haploid facility in Karnataka, India

KARNAKATA, India (CIMMYT) — The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and the University of Agricultural Sciences-Bangalore (UAS-Bangalore) have signed a collaboration agreement for establishing a maize doubled haploid (DH) facility at the Agricultural Research Station in Kunigal (ARS-Kunigal), Tumkur district, Karnataka state, India.

CIMMYT will establish and operate the maize DH facility, including field activities and the associated laboratory. Occupying 12 acres of land, the facility is estimated to produce at least 30,000 DH lines a year. CIMMYT hopes the facility to be operational by the last quarter of 2019.

The maize DH facility, funded by the CGIAR Research Program on Maize (MAIZE), fulfills a very important requirement of the region. It has the potential to accelerate maize breeding and hybrid development and significantly increase genetic gains through maize breeding in Asia. During the 13th Asian Maize Conference in Ludhiana, India (October 8-10, 2018), several partners — including the Indian Institute of Maize Research (ICAR-IIMR) — emphasized the urgent need for a state-of-the-art maize DH facility that could serve breeding programs across Asia.

“This is indeed a major landmark for maize breeding, especially in the public sector, not only in India, but also in Asia,” said B.M. Prasanna, Director of CIMMYT’s Global Maize Program and the CGIAR Research Program on Maize (MAIZE). “The facility will provide maize DH development services, not only for the maize breeding programs of CIMMYT and UAS-B, but also for national agricultural research system institutions and small and medium-sized seed companies engaged in maize breeding and interested to pursue DH-based advanced maize breeding strategies in Asia. DH technology, in combination with molecular marker-assisted breeding, can significantly increase genetic gains in maize breeding.”

“The maize doubled haploid facility … will be the first of its kind in the public domain in Asia,” said S. Rajendra Prasad, Vice Chancellor of UAS-Bangalore. “The work done at this facility will certainly benefit the farmers of the state, country and the Asian region, by accelerating maize breeding and improving efficiencies.”

The signing of the collaboration agreement took place on February 18, 2019 at UAS-Bangalore’s campus in Bengaluru. CIMMYT was represented by B.M. Prasanna and BS Vivek, Senior Maize Breeder. UAS-Bangalore was represented by S. Rajendra Prasad; Mahabaleshwar Hegde, Registrar, and Y.G. Shadakshari, Director of Research.

The benefits of doubled haploid technology

DH maize lines are highly uniform, genetically pure and stable, and enable significant saving of time and resources in deriving parental lines, which are building blocks of improved maize hybrids.

Over the last 12 years, CIMMYT has worked intensively on optimizing DH technology for the tropics. Researchers released first-generation tropicalized haploid inducers in 2012, and second-generation tropicalized haploid inducers in 2017, in partnership with the University of Hohenheim, Germany. In 2017, CIMMYT developed more than 93,000 maize DH lines from 455 populations, and delivered them to maize breeders in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

INTERVIEW OPPORTUNITIES:

B.M. Prasanna – Director of CIMMYT’s Global Maize Program and the CGIAR Research Program on Maize (MAIZE).

FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT THE MEDIA TEAM:

Jennifer Johnson – Maize Communication Officer, CIMMYT. J.A.JOHNSON@cgiar.org, +52 (55) 5804 2004 ext. 1036.

Assessing the effectiveness of a “wheat holiday” for preventing blast in the lower Gangetic plains

Wheat blast — one of the world’s most devastating wheat diseases — is moving swiftly into new territory in South Asia.

In an attempt to curb the spread of this disease, policymakers in the region are considering a “wheat holiday” policy: banning wheat cultivation for a few years in targeted areas. Since wheat blast’s Magnaporthe oryzae pathotype triticum (MoT) fungus can survive on seeds for up to 22 months, the idea is to replace wheat with other crops, temporarily, to cause the spores to die. In India, which shares a border of more than 4,000 km with Bangladesh, the West Bengal state government has already instituted a two-year ban on wheat cultivation in two districts, as well as all border areas. In Bangladesh, the government is implementing the policy indirectly by discouraging wheat cultivation in the severely blast affected districts.

CIMMYT researchers recently published in two ex-ante studies to identify economically feasible alternative crops in Bangladesh and the bordering Indian state of West Bengal.

Alternative crops

The first step to ensuring that a ban does not threaten the food security and livelihoods of smallholder farmers, the authors assert, is to supply farmers with economically feasible alternative crops.

In Bangladesh, the authors examined the economic feasibility of seven crops as an alternative to wheat, first in the entire country, then in 42 districts vulnerable to blast, and finally in ten districts affected by wheat blast. Considering the cost of production and revenue per hectare, the study ruled out boro rice, chickpeas and potatoes as feasible alternatives to wheat due to their negative net return. In contrast, they found that cultivation of maize, lentils, onions, and garlic could be profitable.

The study in India looked at ten crops grown under similar conditions as wheat in the state of West Bengal, examining the economic viability of each. The authors conclude that growing maize, lentils, legumes such as chickpeas and urad bean, rapeseed, mustard and potatoes in place of wheat appears to be profitable, although they warn that more rigorous research and data are needed to confirm and support this transition.

Selecting alternative crops is no easy task. Crops offered to farmers to replace wheat must be appropriate for the agroecological zone and should not require additional investments for irrigation, inputs or storage facilities. Also, the extra production of labor-intensive and export-oriented crops, such as maize in India and potatoes in Bangladesh, may add costs or require new markets for export.

There is also the added worry that the MoT fungus could survive on one of these alternative crops, thus completely negating any benefit of the “wheat holiday.” The authors point out that the fungus has been reported to survive on maize.

A short-term solution?

In both studies, the authors discourage a “wheat holiday” policy as a holistic solution. However, they leave room for governments to pursue it on an interim and short-term basis.

In the case of Bangladesh, CIMMYT agricultural economist and lead author Khondoker Mottaleb asserts that a “wheat holiday” would increase the country’s reliance on imports, especially in the face of rapidly increasing wheat demand and urbanization. A policy that results in complete dependence on wheat imports, he and his co-authors point out, may not be politically attractive or feasible. Also, the policy would be logistically challenging to implement. Finally, since the disease can potentially survive on other host plants, such as weeds and maize, it may not even work in the long run.

In the interim, the government of Bangladesh may still need to rely on the “wheat holiday” policy in the severely blast-affected districts. In these areas, they should encourage farmers to cultivate lentils, onions and garlic. In addition, in the short term, the government should make generic fungicides widely available at affordable prices and provide an early warning system as well as adequate information to help farmers effectively combat the disease and minimize its consequences.

In the case of West Bengal, India, similar implications apply, although the authors conclude that the “wheat holiday” policy could only work if Bangladesh has the same policy in its blast-affected border districts, which would involve potentially difficult and costly inter-country collaboration, coordination and logistics.

Actions for long-term success

The CIMMYT researchers urge the governments of India and Bangladesh, their counterparts in the region and international stakeholders to pursue long-term solutions, including developing a convenient diagnostic tool for wheat blast surveillance and a platform for open data and science to combat the fungus.

A promising development is the blast-resistant (and zinc-enriched) wheat variety BARI Gom 33 which the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (BARI) released in 2017 with support from CIMMYT. However, it will take at least three to five years before it will be available to farmers throughout Bangladesh. The authors urged international donor agencies to speed up the multiplication process of this variety.

CIMMYT scientists in both studies close with an urgent plea for international financial and technical support for collaborative research on disease epidemiology and forecasting, and the development and dissemination of new wheat blast-tolerant and resistant varieties and complementary management practices — crucial steps to ensuring food security for more than a billion people in South Asia.

| Wheat blast impacts

First officially reported in Brazil in 1985, where it eventually spread to 3 million hectares in South America and became the primary reason for limited wheat production in the region, wheat blast moved to Bangladesh in 2016. There it affected nearly 15,000 hectares of land in eight districts, reducing yield by as much as 51 percent in the affected fields. Blast is devilish: directly striking the wheat ear, it can shrivel and deform the grain in less than a week from the first symptoms, leaving farmers no time to act. There are no widely available resistant varieties, and fungicides are expensive and provide only a partial defense. The disease, caused by the fungus Magnaporthe oryzae pathotype triticum (MoT), can spread through infected seeds as well as by spores that can travel long distances in the air. South Asia has a long tradition of wheat consumption, especially in northwest India and Pakistan, and demand has been increasing rapidly across South Asia. It is the second major staple in Bangladesh and India and the principal staple food in Pakistan. Research indicates 17 percent of wheat area in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan — representing nearly 7 million hectares – is vulnerable to the disease, threatening the food security of more than a billion people. |

CIMMYT and its partners work to mitigate wheat blast through projects supported by U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR), the Indian Council for Agricultural Research (ICAR), the CGIAR Research Program on Wheat and the CGIAR Platform for Big Data in Agriculture.

Read the full articles:

- Averting Wheat Blast by Implementing a ‘Wheat Holiday’: In Search of Alternative Crops in West Bengal, India by Khondoker A. Mottaleb, Pawan K. Singh, Kai Sonder, Gideon Kruseman, Olaf Erenstein (PLOS One, February 2019)

- Alternative use of wheat land to implement a potential wheat holiday as wheat blast control: In search of feasible crops in Bangladesh by Khondoker Abdul Mottaleb, Pawan Kumar Singh, Xinyao He, Akbar Hossain, Gideon Kruseman, Olaf Erenstein (Land Use Policy, March 2019)

BISA and PAU awarded for collaborative work on residue management

The Borlaug Institute for South Asia-Punjab Agricultural University (BISA-PAU) joint team recently received an award from the Indian Society for Agricultural Engineers (ISAE) in recognition of their work on rice residue management using the Super Straw Management System, also known as Super SMS.

Developed and recommended by researchers at BISA and PAU in 2016, the Super SMS is an attachment for self-propelled combine harvesters which offers an innovative solution to paddy residue management in rice-wheat systems.

The Punjab government has made the use of the Super SMS mandatory for all combine harvesters in northwestern India.

The Super SMS gives farmers the ability to recycle residues on-site, reducing the need for residue burning and thereby reducing environmental pollution and improving soil health. Instead, the Super SMS helps to uniformly spread rice residue, which is essential for the efficient use of Happy Seeder technology and maintaining soil moisture in the field.

Harminder Singh Sidhu, a senior research engineer with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) working at BISA, stressed the need for more sustainable methods of dealing with residue. “Happy Seeder was found to be a very effective tool for direct sowing of wheat after paddy harvesting, using combine harvesters fitted with Super Straw Management System.”

BISA-PAU researchers received the ISAE Team Award 2018 at the 53rd Annual Convention of ISAE, held from January 28 to January 30, 2019, at Baranas Hindu University in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh state.

The director general of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), Trilochan Mohapatra, presented the award, acknowledging it as “a real team award which is making a difference on the ground.”

The recipients acknowledged the role of local industry partner New Gurdeep Agro Industries for its contributions to promoting the adoption of this machinery. Within eight months of commercialization in the Indian state of Punjab, over 100 manufacturers had begun producing the Super SMS attachment. Currently, more than 5,000 combine harvesters are equipped with it.

Experts identify policy gaps in fertilizer application in India

NEW DELHI (CIMMYT) — Imbalanced application of different plant nutrients through fertilizers is a widespread problem in India. The major reasons are lack of adequate knowledge among farmers about the nutritional requirement of crops, poor access to proper guidelines on the right use of plant nutrients, inadequate policy support through government regulations, and distorted and poorly targeted subsidies.

This context makes it necessary to foster innovation in the fertilizer industry, and also to find innovative ways to target farmers, provide extension services and communicate messages.

A dialogue on “Innovations for promoting balanced application of macro and micro nutrient fertilizers in Indian agriculture” facilitated discussion on this issue. Representatives from key fertilizer industries, state governments, research institutions and the Indian Council of Agricultural Research gathered in New Delhi, India, on December 12, 2018. This dialogue was part of the Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA) and was organized by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and the International Plant Nutrition Institute (IPNI).

The Director General of the Fertilizer Association of India (FAI), Shri Satish Chander, pointed out that new-product approvals in India take approximately 800 days. However, he explained, this delay is not the biggest problem facing the sector: other barriers include existing price controls that are highly contingent on political myths.

IFPRI researcher Avinash Kishore presented evidence contradicting the myth that farmers are highly sensitive to any price change. He presented data demonstrating that farmers’ demand for Urea and DAP remained highly price inelastic during periods of steep price increases, in 2011 and 2012.

The Director of the South Asia Program at IPNI, T. Satyanarayana, highlighted the importance of micronutrients in promoting balanced fertilization of soils and innovative methods for determining soil health.

Andrew McDonald, from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), presented the new Soil Intelligence System for India, which employs innovative approaches to soil health assessments.

Farmers’ representative Ajay Vir Jakhar elaborated on the failure of underfunded extension systems to reach and disseminate relevant, factual and timely messages to vast numbers of farmers.

Other representatives from the fertilizer industry touched upon the need to identify farmer requirements for risk mitigation, labor shortages and site-specific nutrient management needs for custom fertilizer blends. Participants also discussed field evidence related to India’s soil health card scheme. Ultimately, discussions held at the roundtable helped identify relevant policy gaps, which will be summarized into a policy brief.

The Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia project is led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) in partnership with the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) and the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). It is funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

International experts discuss progress and challenges of maize research and development in Asia

The importance of maize in Asian cropping systems has grown rapidly in recent years, with several countries registering impressive growth rates in maize production and productivity. However, increasing and competing demands — food, feed, and industry — highlight the continued need to invest in maize research for development in the region. Maize experts from around the world gathered to discuss these challenges and how to solve them at the 13th Asian Maize Conference and Expert Consultation on Maize for Food, Feed, Nutrition and Environmental Security, held from October 8 to 10, 2018, in Ludhiana, Punjab, India.

More than 280 delegates from 20 countries attended the conference. Technical sessions and panel discussions covered diverse topics such as novel tools and strategies for increasing genetic gains, stress-resilient maize, sustainable intensification of maize-based cropping systems, specialty maize, processing and value addition, and nutritionally enriched maize for Asia.

The international conference was jointly organized by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), the Indian Institute of Maize Research (ICAR-IIMR), Punjab Agricultural University (PAU), the CGIAR Research Program on Maize (MAIZE), and the Borlaug Institute for South Asia (BISA).

In Asia, maize is rapidly growing in its importance, due to high demand. Maize productivity in the region is growing by 5.2 percent annually compared to a global average of 3.5 percent. However, this is not enough. “Asia produces nearly 80 million tons of maize annually, but demand will be double by the year 2050,” said Martin Kropff, CIMMYT director general, in his opening address at the conference. “We need to produce two times more maize in Asia, using two times less inputs, including water and nutrients. Climatic extremes and variability, especially in South and South East Asia, will make this challenge more difficult. Continued funding for maize research is crucial. We need to work together to ensure that appropriate innovations reach the smallholder farmers.”

Climate-resilient maize and sustainable intensification

A major theme emphasized at the conference was climate resilience in maize-based systems. South Asia is a hotspot for vulnerability due to climate change and climate variability, which poses great risks to smallholder farmers. “Climate resilience cannot be brought by only a single technology — it has to be through a judicious mix of several approaches,” said B.M. Prasanna, director of CIMMYT’s Global Maize Program and the CGIAR Research Program on Maize.

Great advances have been made in developing climate-resilient maize for Asia since the last Asian Maize Conference, held in 2014. Many new heat- and drought-tolerant maize varieties have been developed through various projects, such as the Heat Stress Tolerant Maize for Asia (HTMA), and Affordable, Accessible, Asian (AAA) maize projects. Through the HTMA project, over 50 CIMMYT-derived elite heat-tolerant maize hybrids have been licensed to public and private sector partners in Asia during the last three years, and nine heat-tolerant maize hybrids have been released so far in Bangladesh, India and Nepal.

Sustainable intensification of maize-based farming systems has also helped farmers to increase yields while reducing environmental impact, through conservation agriculture and scale-appropriate mechanization. Simple technologies are now available to reduce harvest time by up to 80 percent and hired labor costs by up to 60 percent. Researchers across the region are also working to strengthen the maize value chains.

Science and appropriate technologies

CIMMYT has been focusing on developing and deploying new technologies that can enhance the efficiency of maize breeding programs; these include doubled haploid (DH) technology, high-throughput field-based phenotyping, and genomics-assisted breeding. The conference emphasized on the need for Asian institutions to adapt such new tools and technologies in maize breeding programs.

Another topic of interest was the fall armyworm, an invasive insect pest that has spread through 44 countries in Africa and was recently reported in India for the first time. “This pest can migrate very quickly and doesn’t require visas and passports like we do. It will travel, and Asian nations need to be prepared,” Prasanna said. “However, there is no need for alarm. We will be looking at lessons learned from other regions and will work together to control this pest.”

In addition to grain for food and feed, specialty maize varieties can provide beneficial economic alternatives for smallholder maize farmers. Conference participants had the opportunity to hear from Indian farmers Kanwal Singh Chauhan and Yugandar Y, who have effectively adopted specialty maize varieties, such as baby corn, sweet corn and popcorn, into life-changing economic opportunities for farming communities. They hope to inspire other farmers in the region to do the same.

On October 10, conference delegates participated in a maize field day organized at the BISA farm in Ladhowal, Ludhiana. Nearly 100 improved maize varieties developed by CIMMYT, ICAR and public and private sector partners were on display, in addition to scale-appropriate mechanization options, decision support tools, and precision nutrient and water management techniques.

The conference concluded with a ceremony honoring the winners of the 2018 MAIZE-Asia Youth Innovators Award. The awards were launched in collaboration between the CGIAR Research Program on Maize and YPARD (Young Professionals for Agricultural Development) to recognize the contributions of innovative young women and men who can inspire fellow youth to get involved in improving maize-based agri-food systems in Asia. Winners of the first edition of the awards include Dinesh Panday of Nepal, Jie Xu of China, Samjhana Khanal of Nepal, and Vignesh Muthusamy of India.

Wheat blast screening and surveillance training in Bangladesh

Fourteen young wheat researchers from South Asia recently attended a screening and surveillance course to address wheat blast, the mysterious and deadly disease whose surprise 2016 outbreak in southwestern Bangladesh devastated that region’s wheat crop, diminished farmers’ food security and livelihoods, and augured blast’s inexorable spread in South Asia.

Held from 24 February to 4 March 2018 at the Regional Agricultural Research Station (RARS), Jessore, as part of that facility’s precision phenotyping platform to develop resistant wheat varieties, the course emphasized hands-on practice for crucial and challenging aspects of disease control and resistance breeding, including scoring infections on plants and achieving optimal development of the disease on experimental wheat plots.

Cutting-edge approaches tested for the first time in South Asia included use of smartphone-attachable field microscopes together with artificial intelligence processing of images, allowing researchers identify blast lesions not visible to the naked eye.

“A disease like wheat blast, which respects no borders, can only be addressed through international collaboration and strengthening South Asia’s human and institutional capacities,” said Hans-Joachim Braun, director of the global wheat program of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), addressing participants and guests at the course opening ceremony. “Stable funding from CGIAR enabled CIMMYT and partners to react quickly to the 2016 outbreak, screening breeding lines in Bolivia and working with USDA-ARS, Fort Detrick, USA to identify resistance sources, resulting in the rapid release in 2017 of BARI Gom 33, Bangladesh’s first-ever blast resistant and zinc enriched wheat variety.”

Cooler and dryer weather during the 2017-18 wheat season has limited the incidence and severity of blast on Bangladesh’s latest wheat crop, but the disease remains a major threat for the country and its neighbors, according to P.K. Malaker, Chief Scientific Officer, Wheat Research Centre (WRC) of the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (BARI).

“We need to raise awareness of the danger and the need for effective management, through training courses, workshops, and mass media campaigns,” said Malaker, speaking during the course.

The course was organized by CIMMYT, a Mexico-based organization that has collaborated with Bangladeshi research organizations for decades, with support from the Australian Center for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR), Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), CGIAR Research Program on Wheat (WHEAT), the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Bangladesh Wheat and Maize Research Institute (BWMRI).

Speaking at the closing ceremony, N.C.D. Barma, WRC Director, thanked the participants and the management team and distributed certificates. “The training was very effective. BMWRI and CIMMYT have to work together to mitigate the threat of wheat blast in Bangladesh.”

Innovations for cross-continent collaborations

Australian High Commissioner to India, Harinder Sidhu, visited the Borlaug Institute for South Asia (BISA) in Ladhowal, Ludhiana, India on February 19.

Arun Joshi, Managing Director for BISA & CIMMYT in India, welcomed her with an introduction about the creation, mission and activities of BISA and the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

Sidhu also learned about the work CIMMYT and BISA do in conservation agriculture in collaboration with Punjab Agricultural University, machinery manufacturers and farmers. This work focuses on using and scaling the Happy Seeder, which enables direct seeding of wheat into heavy loads of rice residue without burning. This technology has been called “an agricultural solution to air pollution in South Asia,” as the burning of crop residue is a huge contributor to poor air quality in South Asia. Sidhu learned about recent improvements to the technology, such as the addition of a straw management system to add extra functionality, which has led to the large-scale adoption of the Happy Seeder.

The high commissioner showed keen interest in the Happy Seeder machine, and was highly impressed by the test-wheat-crop planted on 400 acres with the Happy Seeder.

Salwinder Atwal showed Sidhu the experiments using Happy Seeder for commercial seed production, and ML Jat, Principal Researcher at CIMMYT, presented on the innovative research BISA and CIMMYT are doing on precision water, nutrient and genotype management.

Sidhu visited fields with trials of climate resilient wheat as Joshi explained the importance and role of germplasm banks and new approaches such as use of genomic selection in wheat breeding in the modern agriculture to address the current challenges of climate change. He also explained the work CIMMYT does on hybrid wheat for increasing yield potential and breeding higher resistance against wheat rusts and other diseases.

ML Jat, who leads the CIMMYT-CCAFS climate smart agriculture project, explained the concept of climate smart villages and led Sidhu on a visit to the climate smart village of Noorpur Bet, which has been adopted under the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security.

During Sidhu’s visit to Noorpur Bet, a stakeholder consultation was organized on scaling happy seeder technology for promoting no-burning farming. In the stakeholder consultation, stakeholders shared experiences with happy seeder as well as other conservation agriculture amd climate smart agriculture technologies. BS Sidhu, Commissioner of Agriculture for the Government of Punjab chaired the stakeholder consultation and shared his experiences as well as Government of Punjab’s plans and policies for the farmers to promote happy seeder and other climate smart technologies.

“I am very impressed to see all these developments and enthusiasm of the farmers and other stakeholders for scaling conservation agriculture practices for sustaining the food bowl,” said Sidhu. She noted that Punjab and Australia have many things in common and could learn from each other’s experiences. Later she also visited the Punjab Agricultural University and had a meeting with the Vice Chancellor.

This visit and interaction was attended by more than 200 key stakeholders including officers from Govt. of Punjab, ICAR, PAU-KVKs, PACS, BISA- CIMMYT-CCAFS, manufacturers, farmers and custom operators of Happy Seeder.

The Borlaug Institute for South Asia (BISA) is a non-profit international research institute dedicated to food, nutrition and livelihood security as well as environmental rehabilitation in South Asia, which is home to more than 300 million undernourished people. BISA is a collaborative effort involving the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and the Indian Council for Agricultural Research (ICAR).

Success in mainstreaming CSISA-supported agricultural technologies

Since 2015, the Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA) has been working with Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs) – agricultural extension centers created by the Indian Council for Agricultural Research – to generate evidence on best management practices for improving cropping system productivity in the Eastern Indo-Gangetic Plains.

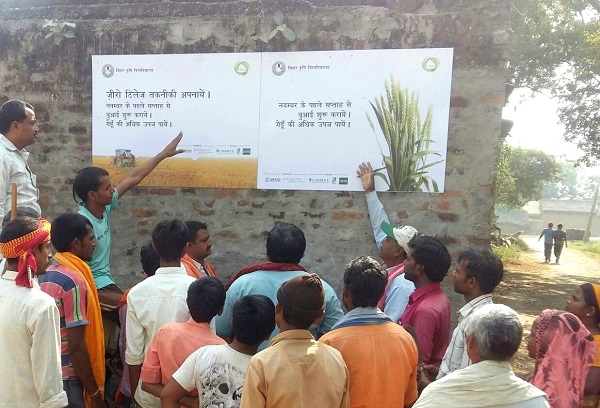

Technologies and management practices essential to this research include early wheat sowing, zero tillage and the timely transplanting of rice. In response to clear evidence generated through the CSISA–KVK partnership, Bihar Agriculture University (BAU) announced in October 2017 that all KVKs in Bihar would promote early wheat sowing starting November 1. KVKs promoted this intervention by placing notices, which were designed by CSISA, on roadsides.

BAU also directed the KVKs to act as commercial paddy nurseries, supplying healthy rice seedlings in a timely manner to farmers.

Pairing these rice and wheat interventions is designed to optimize system productivity through the on-time rice transplanting of rice during Kharif (monsoon growing season), allowing for the timely seeding of zero-till wheat in Rabi (winter growing season).

Under the CSISA–KVK partnership, KVKs have supported early wheat sowing by introducing local farmers to the practice of sowing zero tillage wheat immediately after rice harvesting.

Evidence has shown that early sowing of wheat increases yields across Bihar and Eastern Uttar Pradesh. KVK scientists have begun to see the importance of breaking the tradition of sowing short duration varieties of wheat late in the season, which exposes the crops to higher temperatures and reduces yields.

Across the annual cropping cycle, monsoon variability threatens the rice phase and terminal heat threatens the wheat phase, with significant potential cumulative effects on system productivity. The combined interventions of early wheat sowing, zero tillage wheat and rice nurseries for timely planting help mitigate the effects of both variable monsoon and high temperatures during the grain-filling stage.

In 2016–17, data collected across seven KVKs (333 sites) indicated that yields declined systematically when wheat was planted after November 10. When planting was done on November 20 — yields declined by 4%, November 30 – 15%, December 10 – 30%, reaching a low when planting was done on December 20 of a 40% reduction in yield.

Rice yields are also reduced significantly if transplanting is delayed beyond July 20. The timing of rice cultivation, therefore, is important in facilitating early sowing in wheat without any yield penalty to rice.

KVKs are working to generate awareness of these important cropping system interventions, as well as others, deep in each district in which they work. CSISA supports their efforts and strives to mainstream sustainable intensification technologies and management practices within a variety of public- and private sector extension systems as capacity building are core to CSISA Phase III’s vision of success.

The Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia project is led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center with partners the International Rice Research Institute and the International Food Policy Research Institute and funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Climate insurance for farmers: a shield that boosts innovation

What stands between a smallholder farmer and a bag of climate-adapted seeds? In many cases, it’s the hesitation to take a risk. Farmers may want to use improved varieties, invest in new tools, or diversify what they grow, but they need reassurance that their investments and hard work will not be squandered.

Climate change already threatens crops and livestock; one unfortunately-timed dry spell or flash flood can mean losing everything. Today, innovative insurance products are tipping the balance in farmers’ favor. That’s why insurance is featured as one of 10 innovations for climate action in agriculture, in a new report released ahead of next week’s UN Climate Talks. These innovations are drawn from decades of agricultural research for development by CGIAR and its partners and showcase an array of integrated solutions that can transform the food system.

Index insurance is making a difference to farmers at the frontlines of climate change. It is an essential building block for adapting our global food system and helping farmers thrive in a changing climate. Taken together with other innovations like stress-tolerant crop varieties, climate-informed advisories for farmers, and creative business and financial models, index insurance shows tremendous promise.

The concept is simple. To start with, farmers who are covered can recoup their losses if (for example) rainfall or average yield falls above or below a pre-specified threshold or ‘index’. This is a leap forward compared to the costly and slow process of manually verifying the damage and loss in each farmer’s field. In India, scientists from the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), have worked out the water level thresholds that could spell disaster for rice farmers if exceeded. Combining 35 years of observed rainfall and other data, with high-resolution satellite images of actual flooding, scientists and insurers can accurately gauge the extent of flooding and crop loss to quickly determine who gets payouts.

The core feature of index insurance is to offer a lifeline to farmers, so they can shield themselves from the very worst effects of climate change. But that’s not all. Together with my team, we’re investigating how insurance can help farmers adopt new and improved varieties. Scientists are very good at developing technologies but farmers are not always willing to make the leap. This is one of the most important challenges that we grapple with. What we’ve found has amazed us: buying insurance can help farmers overcome uncertainty and give them the confidence to invest in new innovations and approaches. This is critical for climate change adaptation. We’re also finding that creditors are more willing to lend to insured farmers and that insurance can stimulate entrepreneurship and innovation. Ultimately, insurance can help break poverty traps, by encouraging a transformation in farming.

Insurers at the cutting edge are making it easy for farmers to get coverage. In Kenya, insurance is being bundled into bags of maize seeds, in a scheme led by ACRE Africa. Farmers pay a small premium when buying the seeds and each bag contains a scratch card with a code, which farmers text to ACRE at the time of planting. This initiates coverage against drought for the next 21 days; participating farms are monitored using satellite imagery. If there are enough days without rain, a farmer gets paid instantly via their mobile phone.

Farmers everywhere are businesspeople who seek to increase yields and profits while minimizing risk and losses. As such, insurance has widespread appeal. We’ve seen successful initiatives grow rapidly in India, China, Zambia, Kenya and Mexico, which points to significant potential in other countries and contexts. The farmers most likely to benefit from index insurance are emergent and commercial farmers, as they are more likely than subsistence smallholder farmers to purchase insurance on a continual basis.

It’s time for more investment in index insurance and other innovations that can help farmers adapt to climate change. Countries have overwhelmingly prioritized climate actions in the agriculture sector, and sustained support is now needed to help them meet the goals set out in the Paris Climate Agreement.

Jon Hellin leads the project on weather index-based agricultural insurance as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). This work is done in collaboration with the International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI) at Columbia University, and the CGIAR Research Programs on MAIZE and WHEAT.

Find out more

Report: 10 innovations for climate action in agriculture

Video: Jon Hellin on crop-index insurance for smallholder farmers

Report: Scaling up index insurance for smallholder farmers: Recent evidence and insights.

Website: Weather-related agricultural insurance products and programs – CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS)

Climate-smart agriculture achievements inspire support for BISA-CIMMYT in Bihar, India

The Borlaug Institute for South Asia (BISA), CIMMYT and stakeholders are developing, adapting and spreading climate-smart agriculture technologies throughout Bihar, India. During the 2014-2015 winter season, BISA hosted visits for national and international stakeholders to view the progress of participatory technology adaption modules and climate-smart villages throughout the region.

“It is very encouraging to see the [BISA-CIMMYT’s] trials of new upcoming technology…We will be ready to support this,” wrote Dharmendra Singh, Bihar’s Director of Agriculture, in the visitor book during a state agriculture department visit to one of BISA’s research farms and climate-smart villages in Pusa. BISA, CIMMYT and the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), in collaboration with local stakeholders and farmer groups, established 15 Borlaug climate-smart villages in Samastipur district and 20 in Vaishali district, as part of a 2012 research initiative to test various climate-smart tools, approaches and techniques.

“I could understand conservation agriculture better than ever after seeing the crop and crop geometry in the field today,” wrote Mangla Rai, former Director General of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) & Agriculture Advisor to the Chief Minister of Bihar. Raj Kumar Jat and M.L. Jat, CIMMYT cropping system agronomist and senior cropping system agronomist, respectively, showcased research trials on zero-tillage potato and maize, early-planted dual-purpose wheat, precision nutrient management in maize-wheat systems under conservation agriculture, genotype -by- environment interaction in wheat and crop intensification in rice-wheat systems through introduction of inter-cropping practices. Raj Kumar Jat also gave a presentation on how to increase cropping intensity in Bihar by 300% through timely planting and direct seeding techniques.

“Technologies like direct-seeded rice and zero-till wheat, which save both time and labor, should be adapted and transferred to Bihar’s farmers,” said Thomas A. Lumpkin, CIMMYT director general, at a meeting of the CIMMYT Board of Trustees with the Chief Minister of Bihar and other government representatives. “BISA is a key partner in building farmer and extension worker capacity, in addition to testing and promoting innovative agriculture technologies.”

“State agriculture officials should support BISA to hold trainings on direct-seeded rice for fast dissemination across Bihar,” agreed Vijay Chaudhary, Agriculture Minister of Bihar, at a BISA field day. Chaudhary along with 600 farmers and officials visited a climate-smart village where farmers plant wheat using zero tillage. Zero-till wheat is sown directly into soil and residues from previous crops, allowing farmers to plant seed early and to avoid losing yields due to pre-monsoon heat later in the season. Direct-seeded rice is sown and sprouted directly in the field, eliminating labor- and water-intensive seedling nurseries.

During the Bihar Festival, 22-24 March, BISA-CIMMYT showcased conservation agriculture practices and live demonstrations of quality protein maize-based food products, with over 10,000 famers and visitors participating. Vijoy Prakash, Agriculture Production Commissioner of Bihar, and other Bihar government officials discussed with farmers about new BISA-CIMMYT agriculture practices and emphasized the need to “introduce conservation agriculture in the state government’s agricultural technology dissemination program.” Prakash, along with government representatives, has approved two BISA proposals for a training hostel and research.