For development expert Paula Kantor, gender equality was crucial

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) – Paula Kantor had an exceptionally sharp, analytical mind and a deep understanding of how change can empower men and women to give them greater control over their own lives, helping them shape their future direction, said a former colleague.

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) – Paula Kantor had an exceptionally sharp, analytical mind and a deep understanding of how change can empower men and women to give them greater control over their own lives, helping them shape their future direction, said a former colleague.

Kantor, a gender and development specialist working with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), died tragically on May 13 at age 46, in the aftermath of a Taliban attack on the hotel where she was staying in Kabul, Afghanistan.

At the time, she was working on a new CIMMYT research project focused on understanding the role of gender in the livelihoods of people in major wheat-growing areas of Afghanistan, Ethiopia and Pakistan.

The aim of the three-year project, supported by Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), is to find out how wheat research-and-development can contribute to gender equality in conservative contexts so that, in turn, gender equality can contribute more to overall development.

“Paula’s research was targeting a very large populace facing serious threats to both food security and gender equality,” said Lone Badstue, gender specialist at CIMMYT, an international research organization, which works to sustainably increase the productivity of maize and wheat to ensure global food security, improve livelihoods and reduce poverty.

“Paula had vast experience – she spent most of her working life in these contexts – in very patriarchal societies – and had a great love for the people living in these regions. She also had a deep understanding of what she felt needed to change so that both men and women could have a better chance to influence their own lives and choose their own path.”

Kantor, a U.S. citizen, was no stranger to Afghanistan. Several years before joining CIMMYT, she had been based in Kabul where she worked as director and manager of the gender and livelihoods research portfolios at the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU), an independent research agency, from 2008 to 2010.

The project Kantor was working on at the time of her death builds on the idea that research and development interventions should be informed by a socio-cultural understanding of context and local experience, Badstue said.

Ultimately, this approach lays the groundwork for a more effective, equitable development process with positive benefits for all, she added.

WHEAT AND GENDER

Globally, wheat is vital to food security, providing 20 percent of calories and protein consumed, research shows. In Afghanistan, wheat provides more than half of the food supply, based on a daily caloric intake of 2,500 calories, while in Pakistan wheat provides more than a third of food supply, and in Ethiopia it provides about 13 percent of calories, according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the Global Food Security Index. These data do not reflect gender disparity with regard to food access.

In Afghanistan, Ethiopia and Pakistan, the central role of wheat in providing food security makes it an important part of political stability. Overall, gender inequality and social disparities have a negative impact on general economic growth, development, food security and nutrition in much of the developing world, but particularly in these three countries, Badstue said.

Women make up between 32 to 45 percent of economically active people in agriculture in the three countries, which are classified by the U.N. Development Programme’s Gender Inequality Index in the “low human development” category.

Although women play a crucial role in farming and food production, they often face greater constraints in agricultural production than men, Badstue added.

Additionally, rural women are less likely than men to own land or livestock, adopt new technologies, access credit, financial services, or receive education or extension advice, according to the FAO.

Globally, if women had the same access to agricultural production resources as men, they could increase crop yields by up to 30 percent, which would raise total agricultural output in developing countries by as much as 4 percent, reducing the number of hungry people by up to 150 million or 17 percent, FAO statistics show.

“Addressing gender disparities between women and men farmers in the developing world offers significant development potential,” Badstue said.

“Improvements in gender equality often lead to enhanced economic efficiency and such other beneficial development outcomes as improved access to food, nutrition, and education in families.”

METICULOUS RESEARCHER

Paula was brilliant,” Badstue said. “She had a clear edge. She was someone who insisted on excellence methodologically and analytically. She was very well equipped to research issues in this context because of her extensive experience in Afghanistan, as well as her considerate and respectful manner.”

Kantor’s involvement in “Gennovate,” a collaborative, comparative research initiative by gender researchers from a series of international agricultural research centers, was also critical, Badstue said.

The group focuses on understanding gender norms and how they influence the ability of people to access, try out, adopt or adapt new agricultural technology. Kantor provided key analytical and theoretical guidance, inspiring the group to take action and ensure that Gennovate took hold.

Kantor’s work went beyond a focus on solving practical problems to explore underlying power differences within the family or at a local level.

“Agricultural technology that makes day-to-day work in the field easier is crucial, but if it doesn’t change your overall position, if it doesn’t give you a voice, then it changes an aspect of your life without addressing underlying power dynamics,” Badstue said.

“Paula was trying to facilitate lasting change – she wasn’t banging a particular agenda, trying to force people into a particular mind-set. She was really interested in finding the space for manoeuver and the agency of every individual to decide what direction to take in their own life. She was a humanist and highly respected throughout the gender-research community.”

Before joining CIMMYT, Kantor served as a senior gender scientist with the CGIAR’s WorldFish organization for three years from 2012. She also worked at the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) in Washington, D.C., developing intervention research programs in the area of gender and rural livelihoods, including a focus on gender and agricultural value chains.

A funeral mass will be held for Paula Kantor at 11 a.m. on June 11, 2015 at St Leo the Great Catholic Church in Winston Salem, North Carolina.

CIMMYT will hold a memorial service for Paula Kantor on Friday, June 12, 2015 at 12:30 p.m. at its El Batan headquarters near Mexico City.

Gender research and outreach should engage men more effectively, according to Paula Kantor, CIMMYT gender and development specialist who is leading an ambitious new project to empower and improve the livelihoods of women, men and youth in wheat-growing areas of Afghanistan, Ethiopia and Pakistan.

Gender research and outreach should engage men more effectively, according to Paula Kantor, CIMMYT gender and development specialist who is leading an ambitious new project to empower and improve the livelihoods of women, men and youth in wheat-growing areas of Afghanistan, Ethiopia and Pakistan.

The training was for young scientists from different wheat research stations of India involved in a BMZ-funded project to increase the productivity of wheat under rising temperatures and water scarcity in South Asia. The training program attendees’ enhanced understanding of existing molecular tools for wheat breeding as well as emerging tools such as genomic selection. “Molecular tools will play an increasing role in wheat breeding to meet challenges in coming decades,” said Indu Sharma, director of DWR in Karnal. The program covered both theory and practice on the use of molecular makers in wheat breeding, especially those related to vernalization, photoperiodism and earliness per se, which could be used to enhance early heat tolerance. Practical sessions in the molecular laboratory of DWR focused on extraction of DNA, quantification and quality control of DNA, polymerase chain reaction polymerase chain reaction amplification and electrophoresis.

The training was for young scientists from different wheat research stations of India involved in a BMZ-funded project to increase the productivity of wheat under rising temperatures and water scarcity in South Asia. The training program attendees’ enhanced understanding of existing molecular tools for wheat breeding as well as emerging tools such as genomic selection. “Molecular tools will play an increasing role in wheat breeding to meet challenges in coming decades,” said Indu Sharma, director of DWR in Karnal. The program covered both theory and practice on the use of molecular makers in wheat breeding, especially those related to vernalization, photoperiodism and earliness per se, which could be used to enhance early heat tolerance. Practical sessions in the molecular laboratory of DWR focused on extraction of DNA, quantification and quality control of DNA, polymerase chain reaction polymerase chain reaction amplification and electrophoresis. On 03 January 2013, 63-year-old Ghanaian-born maize breeder Strafford Twumasi-Afriyie succumbed to cancer, leaving a substantive legacy that includes the creation of the world’s most widely-sown quality protein maize (QPM) variety,

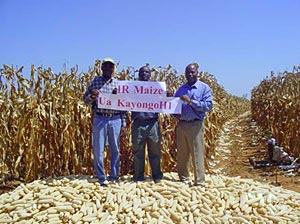

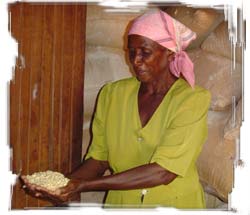

On 03 January 2013, 63-year-old Ghanaian-born maize breeder Strafford Twumasi-Afriyie succumbed to cancer, leaving a substantive legacy that includes the creation of the world’s most widely-sown quality protein maize (QPM) variety,  Looks can deceive. Striga, a deadly parasitic plant, produces a lovely flower but sucks the life and yields out of crops across Africa and Asia. A new strain of improved maize seed is helping farmers reclaim their invaded crop lands.

Looks can deceive. Striga, a deadly parasitic plant, produces a lovely flower but sucks the life and yields out of crops across Africa and Asia. A new strain of improved maize seed is helping farmers reclaim their invaded crop lands.

CIMMYT’s partnerships on maize in eastern Africa hark back to the 1960s, when the center was launched. Formal networking since that time with researchers and extension workers, policy makers, non-government organizations, seed companies, millers, and farmers have culminated in successful breeding and dissemination teams and promising new varieties rated highly by farmers. Awards to teams in Tanzania and Ethiopia recently highlighted the value of these partnerships.

CIMMYT’s partnerships on maize in eastern Africa hark back to the 1960s, when the center was launched. Formal networking since that time with researchers and extension workers, policy makers, non-government organizations, seed companies, millers, and farmers have culminated in successful breeding and dissemination teams and promising new varieties rated highly by farmers. Awards to teams in Tanzania and Ethiopia recently highlighted the value of these partnerships. Two years after its release by Western Seed Company, WH502, a hybrid maize variety derived from research by CIMMYT and partners in eastern Africa, was being grown by nearly a fifth of the farmers surveyed in western Kenya for its high yields, resistance to lodging, tolerance to low nitrogen soils, and other good qualities.

Two years after its release by Western Seed Company, WH502, a hybrid maize variety derived from research by CIMMYT and partners in eastern Africa, was being grown by nearly a fifth of the farmers surveyed in western Kenya for its high yields, resistance to lodging, tolerance to low nitrogen soils, and other good qualities. Farmer Hendrixious Zvamarima, of Shamva village, in Mashonaland Central Province, Zimbabwe, saw a neighbor who, instead of cultivating the soil, sowed his maize seed directly into unplowed soil and residues from last year’s crop. “I was wasting my time using the plow,” says Zvamarima, “so I decided to try the new methods.”

Farmer Hendrixious Zvamarima, of Shamva village, in Mashonaland Central Province, Zimbabwe, saw a neighbor who, instead of cultivating the soil, sowed his maize seed directly into unplowed soil and residues from last year’s crop. “I was wasting my time using the plow,” says Zvamarima, “so I decided to try the new methods.”

In the war against drought each victory is very hard-fought. Stress tolerant maize will make a difference.

In the war against drought each victory is very hard-fought. Stress tolerant maize will make a difference. CIMMYT maize helps villagers quadruple their yields.

CIMMYT maize helps villagers quadruple their yields.