Improved metrics for better decisions

By adopting best practices and established modern tools, national agricultural research systems (NARS) are making data-driven decisions to boost genetic improvement. And they are measuring this progress through tracking and setting goals around “genetic gain.”

Genetic gain means improving seed varieties so that they have a better combination of genes that contribute to desired traits such as higher yields, drought resistance or improved nutrition. Or, more technically, genetic gain measures, “the expected or realized change in average breeding value of a population over at least one cycle of selection for a particular trait of index of traits,” according to the CGIAR Excellence in Breeding (EiB)’s breeding process assessment manual.

CGIAR breeders and their national partners are committed to increasing this rate of improvement to at least 1.5% per year. So, it has become a vital and universal high-level key performance indicator (KPI) for breeding programs.

“We are moving towards a more data-driven culture where decisions are not taken any more based on gut feeling,” EiB’s Eduardo Covarrubias told nearly 200 NARS breeders in a recent webinar on Enhancing and Measuring Genetic Gain. “Decisions that can affect the sustainability and the development of organization need to be based on facts and data.”

Improved metrics. Better decisions. More and better food. But how are NARS positioned to better measure and boost the metric?

EiB researchers have been working with both CGIAR breeding programs and NARS to broaden the understanding of genetic gain and to supply partners with methods and tools to measure it.

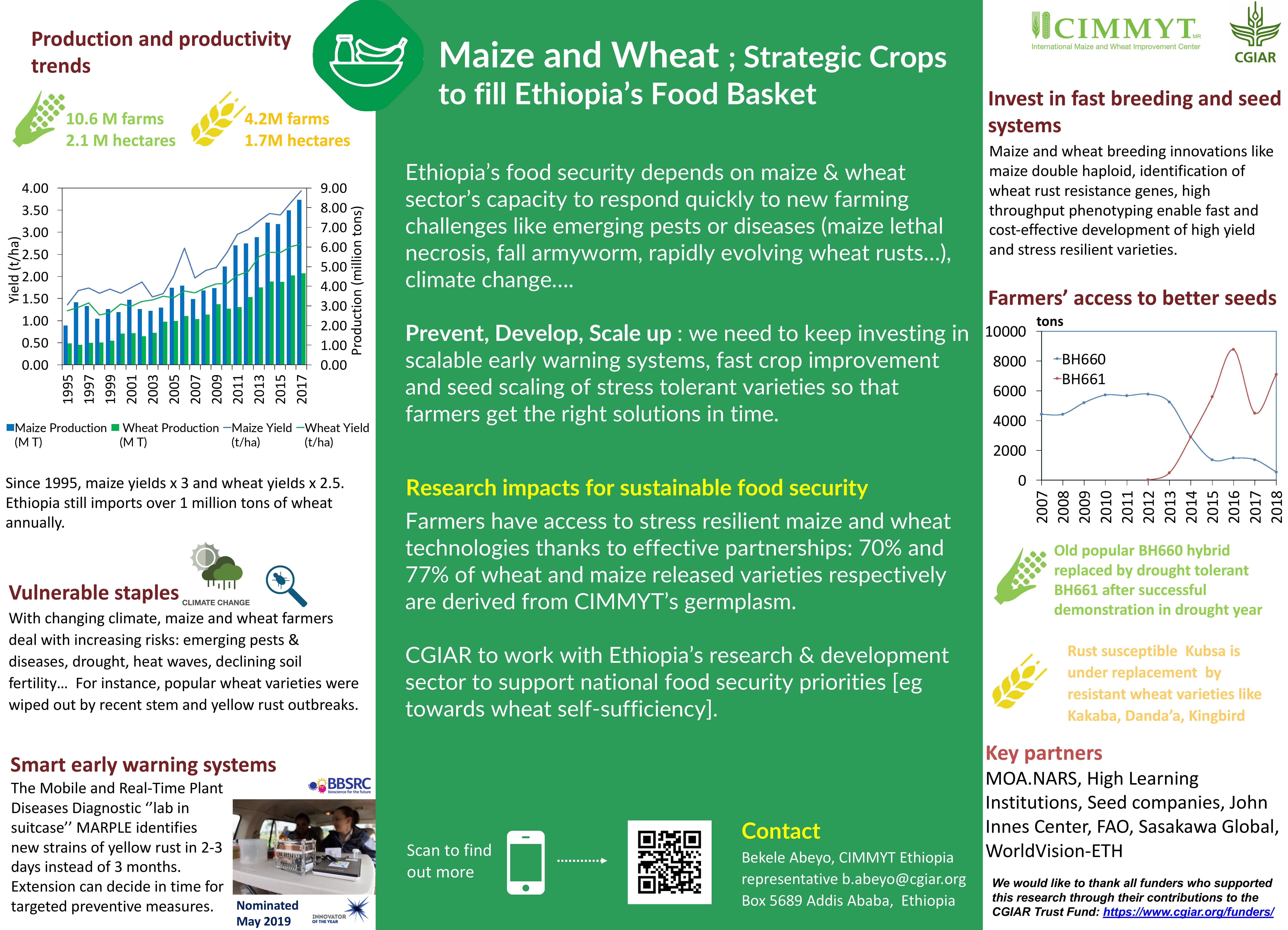

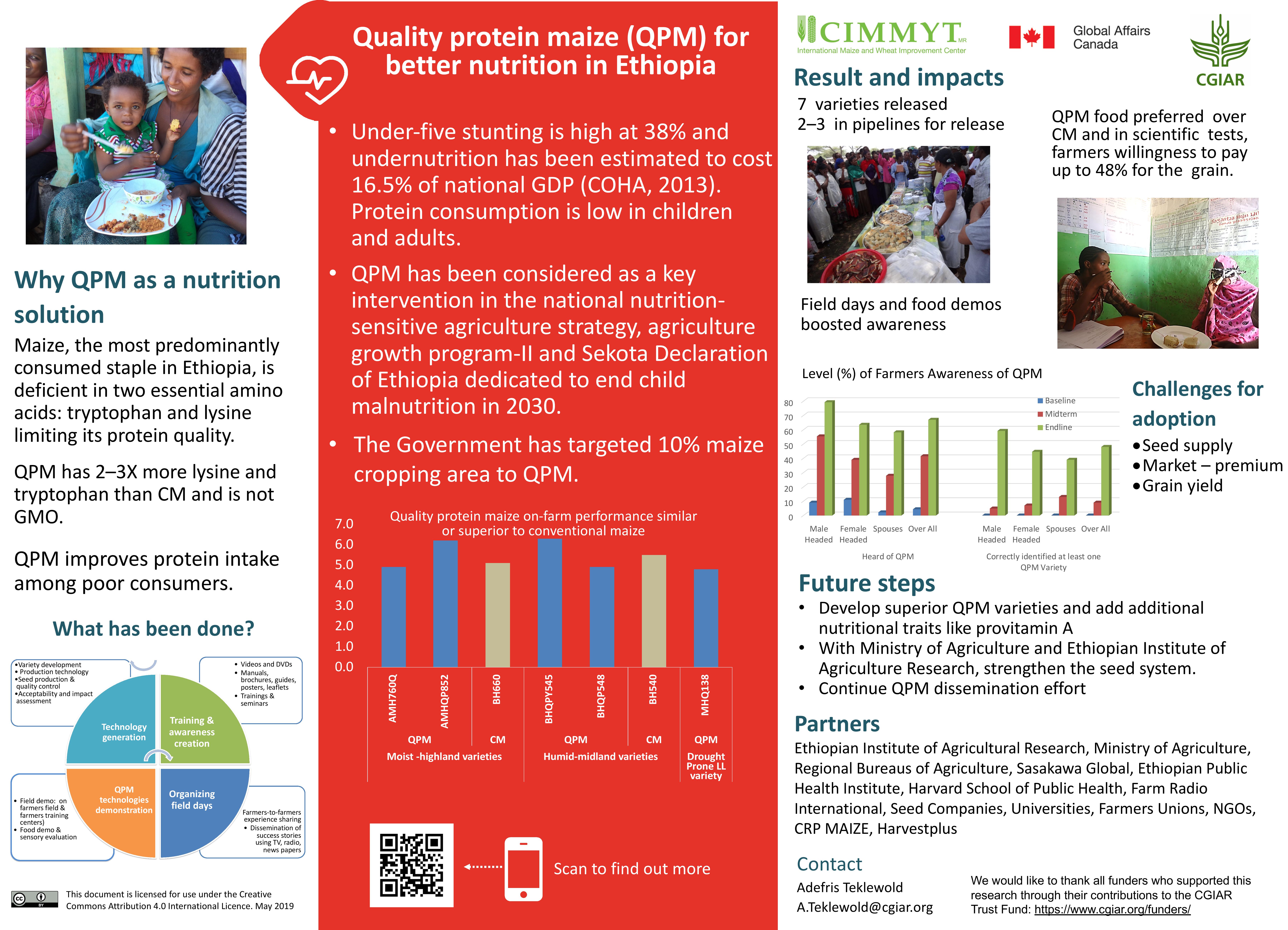

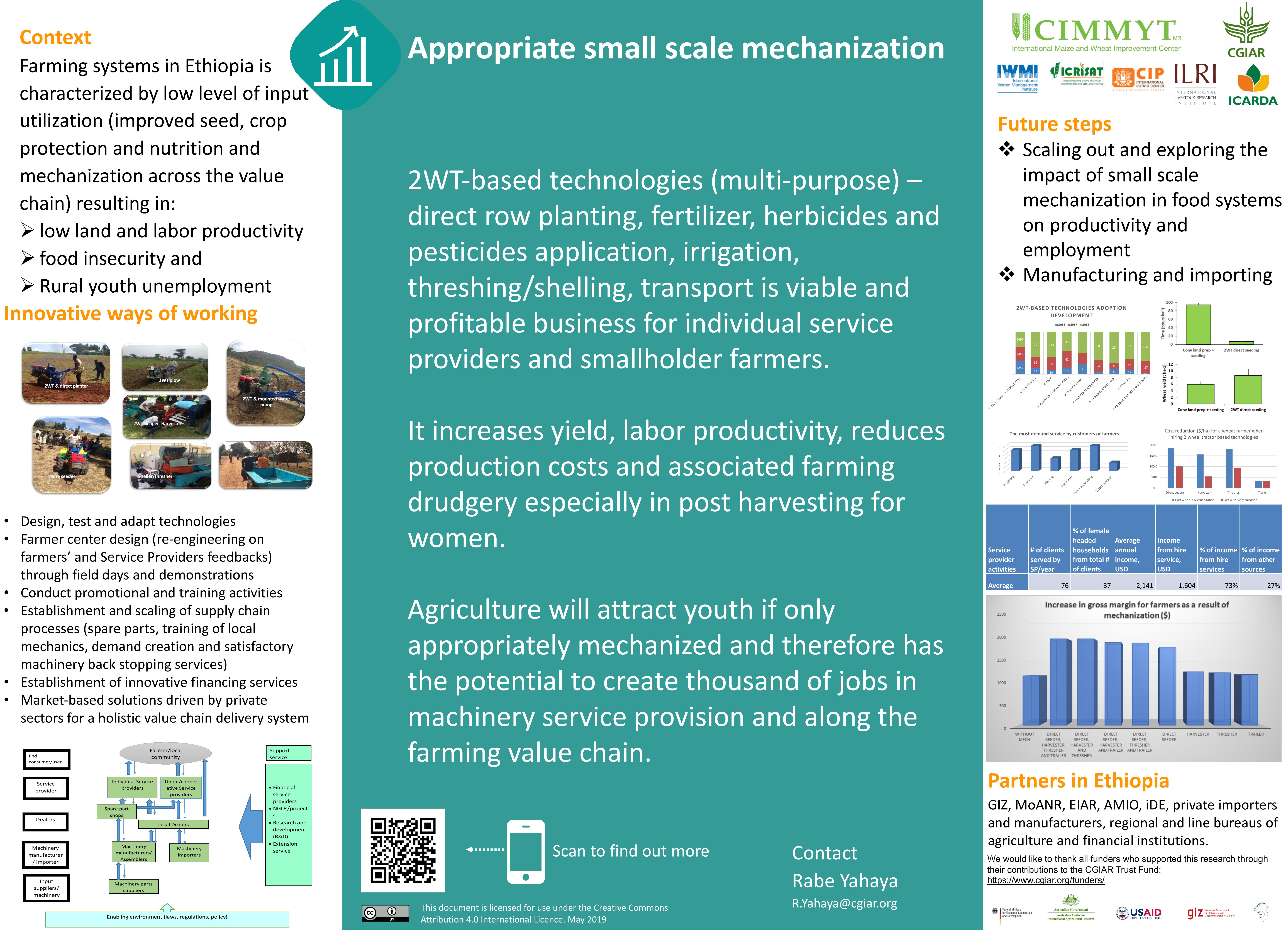

The recent webinar, co-sponsored by EiB and the CIMMYT-led Accelerating Genetic Gains in Maize and Wheat (AGG) project, highlighted tools and services that NARS are accessing, such as genotyping, data analysis and mechanization.

Through program assessments, customized expert advice, training and provision of services and resources, EiB researchers are helping national partners arrive at the best processes for driving and measuring genetic gains in their programs.

For example, the EiB team, through Crops to End Hunger (CtEH), is providing guidelines to breeders to help them maximize the accuracy and precision, while reducing the cost of calculating genetic gains. The guidelines make recommendations such as better design of trials and implementing an appropriate check strategy that permits regular and accurate calculation of genetic gain.

A comprehensive example at the project level is EiB’s High-Impact Rice Breeding in East and West Africa (Hi-Rice), which is supporting the modernization of national rice programs in eight key rice-producing countries in Africa. Hi-Rice delivers training and support to modernize programs through tools such as the use of formalized, validated product profiles to better define market needs, genotyping tools for quality control, and digitizing experiment data to better track and improve breeding results. This is helping partners replace old varieties of rice with new ones that have higher yields and protect against elements that attack rice production, such as drought and disease. Over the coming years, EiB researchers expect to see significant improvements in genetic gain from the eight NARS program partners.

And in the domain of wheat and maize, AGG is working in 13 target countries to help breeders adopt best practices and technologies to boost genetic gain. Here, the EiB team is contributing its expertise in helping programs develop their improvement plans — to map out where, when and how programs will invest in making changes.

NARS and CGIAR breeding programs also have access to tools and expertise on adopting a continuous improvement process — one that leads to cultural change and buy-in from leadership so that programs can identify problems and solve them as they come up. Nearly 150 national breeding partners attended another EiB/AGG webinar highlighting continuous improvement key concepts and case studies.

National programs are starting to see the results of these partnerships. The Kenya Agricultural & Livestock Research Organization (KALRO)’s highland maize breeding program has undertaken significant changes to its pipelines. KALRO carried out its first-ever full program costing, and based on this are modifying their pipeline to expand early stage testing. They are also switching to a double haploid breeding scheme with support from the CGIAR Research Program on Maize (MAIZE), in addition to ring fencing their elite germplasm for future crosses.

KALRO has also adopted EiB-supported data management tools, and are working with the team to calculate past rates of genetic gains for their previous 20 years of breeding. These actions — and the resulting data — will help them decide on which tools and methods to adopt in order to improve the rate of genetic gain for highland maize.

“By analyzing historical genetic gain over the last 20 years, it would be interesting to determine if we are still making gains or have reached a plateau,” said KALRO’s Dickson LIgeyo, who presented a Story of Excellence at EiB’s Virtual Meeting 2020. “The assessment will help us select the right breeding methods and tools to improve the program.”

Other NARS programs are on a similar path to effectively measure and increase genetic gain. In Ghana, the rice breeding program at Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) have developed product profiles, identified their target market segments, costed out their program, digitized their operations, and have even deployed molecular markers for selection.

With this increased expertise and access to tools and services, national breeding programs are set to make great strides on achieving genetic gain goals.

“NARS in Africa and beyond have been aggressively adopting new ideas and tools,” says EiB’s NARS engagement lead Bish Das. “It will pay a lot of dividends, first through the development of state-of-the-art, and ultimately through improving genetic gains in farmers’ fields. And that’s what it’s all about.”