Plant breeding innovations

What is plant breeding?

Emerging in the last 120 years, science-based plant breeding begins by creating novel diversity from which useful new varieties can be identified or formed. The most common approach is making targeted crosses between parents with complementary, desirable traits. This is followed by selection among the resulting plants to obtain improved types that combine desired traits and performance. A less common approach is to expose plant tissues to chemicals or radiation that stimulate random mutations of the type that occur in nature, creating diversity and driving natural selection and evolution.

Determined by farmers and consumer markets, the target traits for plant breeding can include improved grain and fruit yield, resistance to major diseases and pests, better nutritional quality, ease of processing, and tolerance to environmental stresses such as drought, heat, acid soils, flooded fields and infertile soils. Most traits are genetically complex — that is, they are controlled by many genes and gene interactions — so breeders must intercross and select among hundreds of thousands of plants over generations to develop and choose the best.

Plant breeding over the last 100 years has fostered food and nutritional security for expanding populations, adapted crops to changing climates, and helped to alleviate poverty. Together with better farming practices, improved crop varieties can help to reduce environmental degradation and to mitigate climate change from agriculture.

Is plant breeding a modern technique?

Plant breeding began around 10,000 years ago, when humans undertook the domestication of ancestral food crop species. Over the ensuing millennia, farmers selected and re-sowed seed from the best grains, fruits or plants they harvested, genetically modifying the species for human use.

Modern, science-based plant breeding is a focused, systematic and swifter version of that process. It has been applied to all crops, among them maize, wheat, rice, potatoes, beans, cassava and horticulture crops, as well as to fruit trees, sugarcane, oil palm, cotton, farm animals and other species.

With modern breeding, specialists began collecting and preserving crop diversity, including farmer-selected heirloom varieties, improved varieties and the crops’ undomesticated relatives. Today hundreds of thousands of unique samples of diverse crop types, in the form of seeds and cuttings, are meticulously preserved as living catalogs in dozens of publicly-administered “banks.”

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) manages a germplasm bank containing more than 180,000 unique maize- and wheat-related seed samples, and the Svalbard Global Seed Vault on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen preserves back-up copies of nearly a million collections from CIMMYT and other banks.

Through genetic analyses or growing seed samples, scientists comb such collections to find useful traits. Data and seed samples from publicly-funded initiatives of this type are shared among breeders and other researchers worldwide. The complete DNA sequences of several food crops, including rice, maize, and wheat, are now available and greatly assist scientists to identify novel, useful diversity.

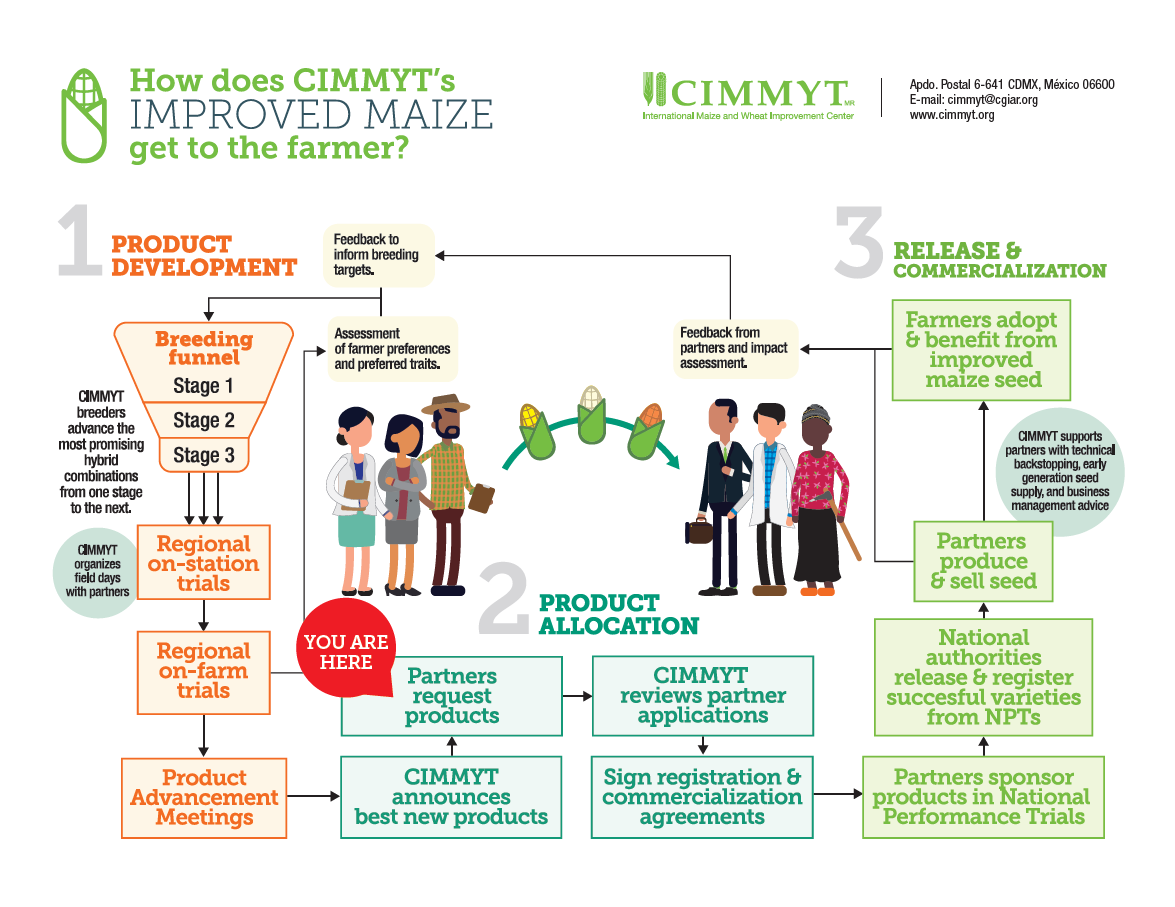

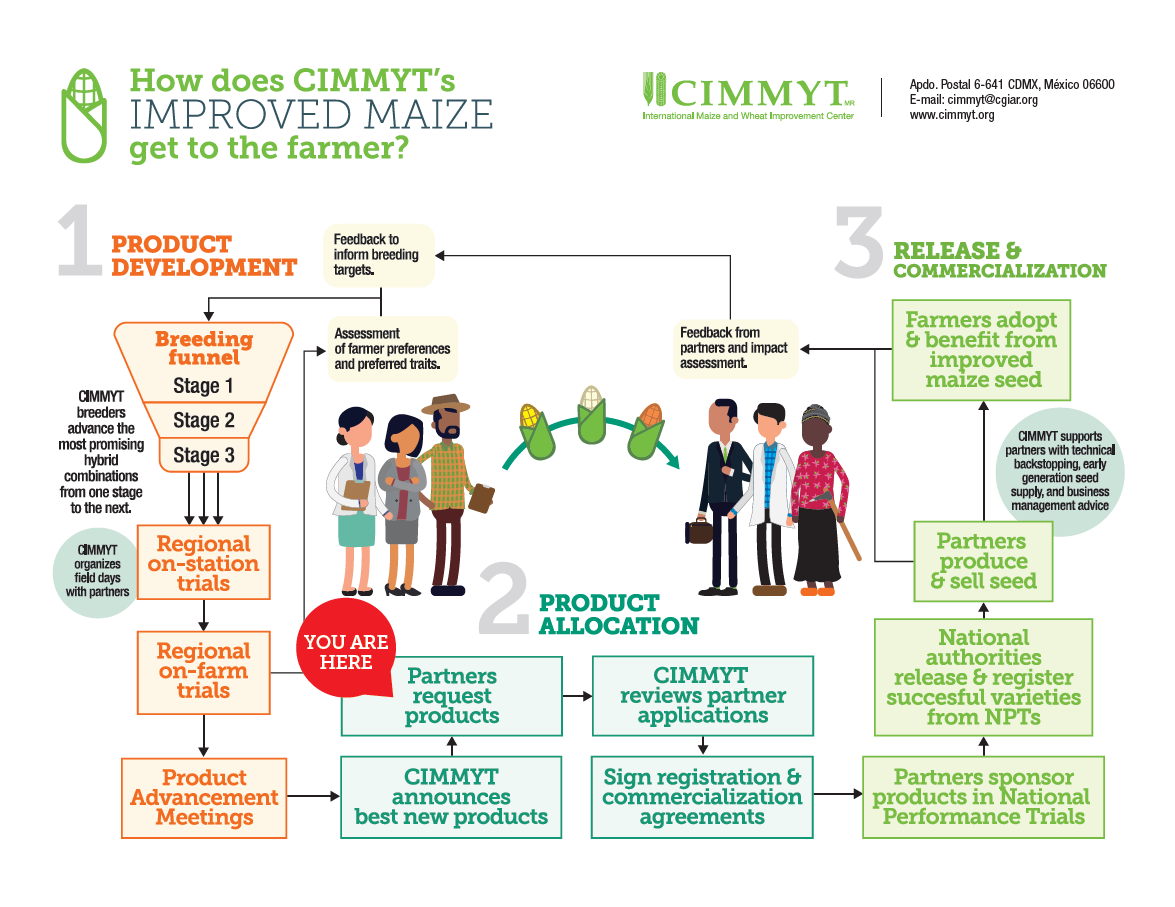

Much crop breeding is international. From its own breeding programs, CIMMYT sends half a million seed packages each year to some 800 partners, including public research institutions and private companies in 100 countries, for breeding, genetic analyses and other research.

A century of breeding innovations

Early in the 20th century, plant breeders began to apply the discoveries of Gregor Mendel, a 19th-century mathematician and biologist, regarding genetic variation and heredity. They also began to take advantage of heterosis, commonly known as hybrid vigor, whereby progeny of crosses between genetically different lines will turn out stronger or more productive than their parents.

Modern statistical methods to analyze experimental data have helped breeders to understand differences in the performance of breeding offspring; particularly, how to distinguish genetic variation, which is heritable, from environmental influences on how parental traits are expressed in successive generations of plants.

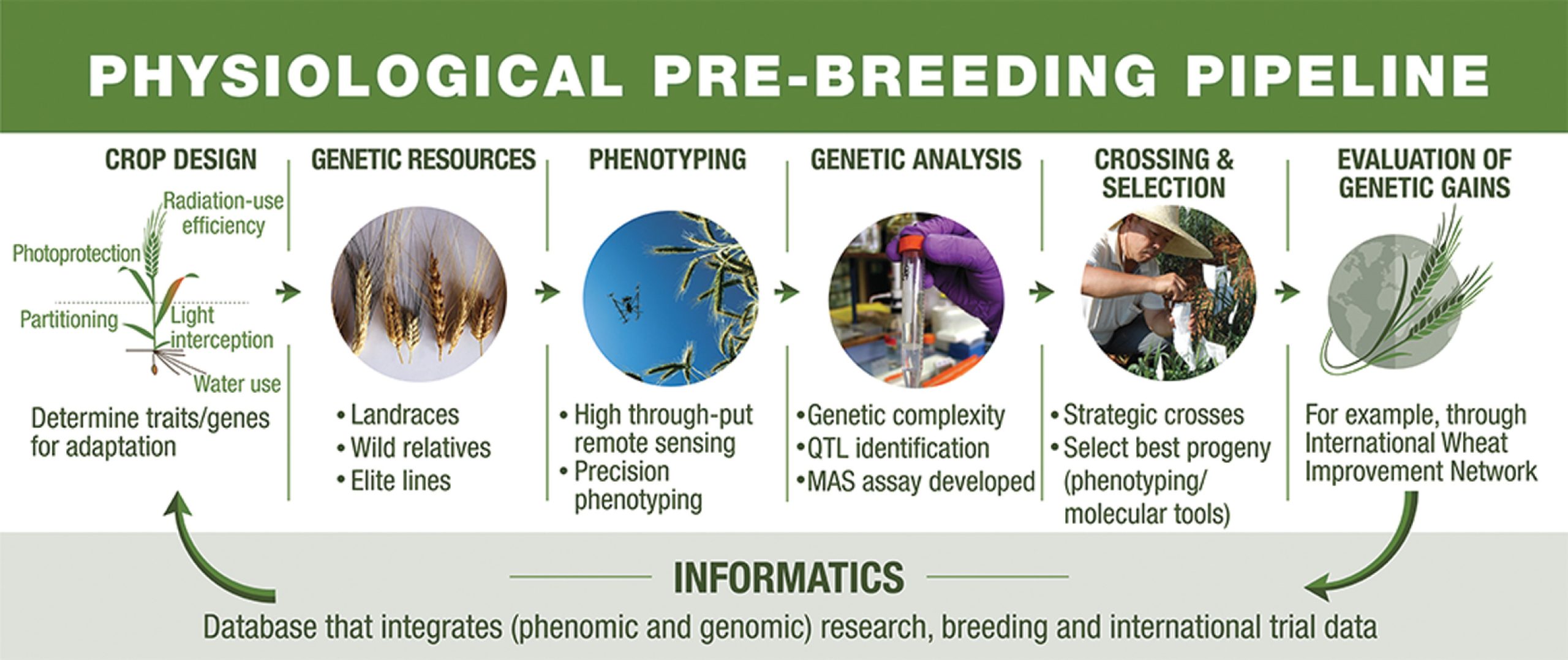

Since the 1990s, geneticists and breeders have used molecular (DNA-based) markers. These are specific regions of the plant’s genome that are linked to a gene influencing a desired trait. Markers can also be used to obtain a DNA “fingerprint” of a variety, to develop detailed genetic maps and to sequence crop plant genomes. Many applications of molecular markers are used in plant breeding to select progenies of breeding crosses featuring the greatest number of desired traits from their parents.

Plant breeders normally prefer to work with “elite” populations that have already undergone breeding and thus feature high concentrations of useful genes and fewer undesirable ones, but scientists also introduce non-elite diversity into breeding populations to boost their resilience and address threats such as new fungi or viruses that attack crops.

Transgenics are products of one genetic engineering technology, in which a gene from one species is inserted in another. A great advantage of the technology for crop breeding is that it introduces the desired gene alone, in contrast to conventional breeding crosses, where many undesired genes accompany the target gene and can reduce yield or other valuable traits. Transgenics have been used since the 1990s to implant traits such as pest resistance, herbicide tolerance, or improved nutritional value. Transgenic crop varieties are grown on more than 190 million hectares worldwide and have increased harvests, raised farmers’ income and reduced the use of pesticides. Complex regulatory requirements to manage their potential health or environmental risks, as well as consumer concerns about such risks and the fair sharing of benefits, make transgenic crop varieties difficult and expensive to deploy.

Genome editing or gene editing techniques allow precise modification of specific DNA sequences, making it possible to enhance, diminish or turn off the expression of genes and to convert them to more favorable versions. Gene editing is used primarily to produce non-transgenic plants like those that arise through natural mutations. The approach can be used to improve plant traits that are controlled by single or small numbers of genes, such as resistance to diseases and better grain quality or nutrition. Whether and how to regulate gene edited crops is still being defined in many countries.

Selected impacts of maize and wheat breeding

In the early 1990s, a CIMMYT methodology led to improved maize varieties that tolerate moderate drought conditions around flowering time in tropical, rainfed environments, besides featuring other valuable agronomic and resilience traits. By 2015, almost half the maize-producing area in 18 countries of sub-Saharan Africa — a region where the crop provides almost a third of human calories but where 65% of maize lands face at least occasional drought — was sown to varieties from this breeding research, in partnership with the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA). The estimated yearly benefits are as high as $1 billion.

Intensive breeding for resistance to Maize Lethal Necrosis (MLN), a viral disease that appeared in eastern Africa in 2011 and quickly spread to attack maize crops across the continent, allowed the release by 2017 of 18 MLN-resistant maize hybrids.

Improved wheat varieties developed using breeding lines from CIMMYT or the International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) cover more than 100 million hectares, nearly two-thirds of the area sown to improved wheat worldwide, with benefits in added grain that range from $2.8 to 3.8 billion each year.

Breeding for resistance to devastating crop diseases and pests has saved billions of dollars in crop losses and reduced the use of costly and potentially harmful pesticides. A 2004 study showed that investments since the early 1970s in breeding for resistance in wheat to the fungal disease leaf rust had provided benefits in added grain worth 5.36 billion 1990 US dollars. Global research to control wheat stem rust disease saves wheat farmers the equivalent of at least $1.12 billion each year.

Crosses of wheat with related crops (rye) or even wild grasses — the latter known as wide crosses — have greatly improved the hardiness and productivity of wheat. For example, an estimated one-fifth of the elite wheat breeding lines in CIMMYT international yield trials features genes from Aegilops tauschii, commonly known as “goat grass,” that boost their resilience and provide other valuable traits to protect yield.

Biofortification — breeding to develop nutritionally enriched crops — has resulted in more than 60 maize and wheat varieties whose grain offers improved protein quality or enhanced levels of micro-nutrients such as zinc and provitamin A. Biofortified maize and wheat varieties have benefited smallholder farm families and consumers in more than 20 countries across sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Consumption of provitamin-A-enhanced maize or sweet potato has been shown to reduce chronic vitamin A deficiencies in children in eastern and southern Africa. In India, farmers have grown a high-yielding sorghum variety with enhanced grain levels of iron and zinc since 2018 and use of iron-biofortified pearl millet has improved nutrition among vulnerable communities.

The future

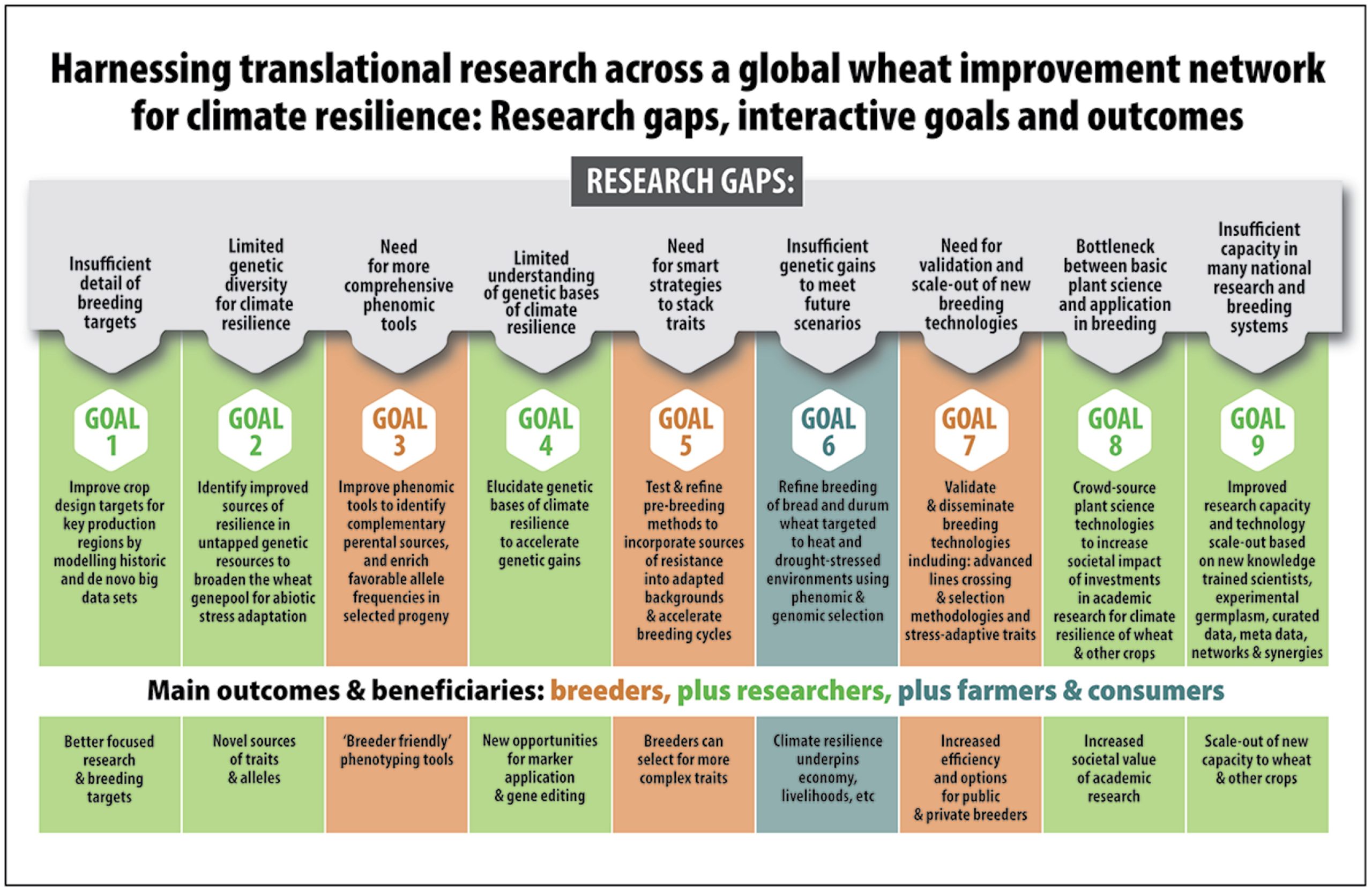

Crop breeders have been laying the groundwork to pursue genomic selection. This approach takes advantage of low-cost, genome-wide molecular markers to analyze large populations and allow scientists to predict the value of particular breeding lines and crosses to speed gains, especially for improving genetically complex traits.

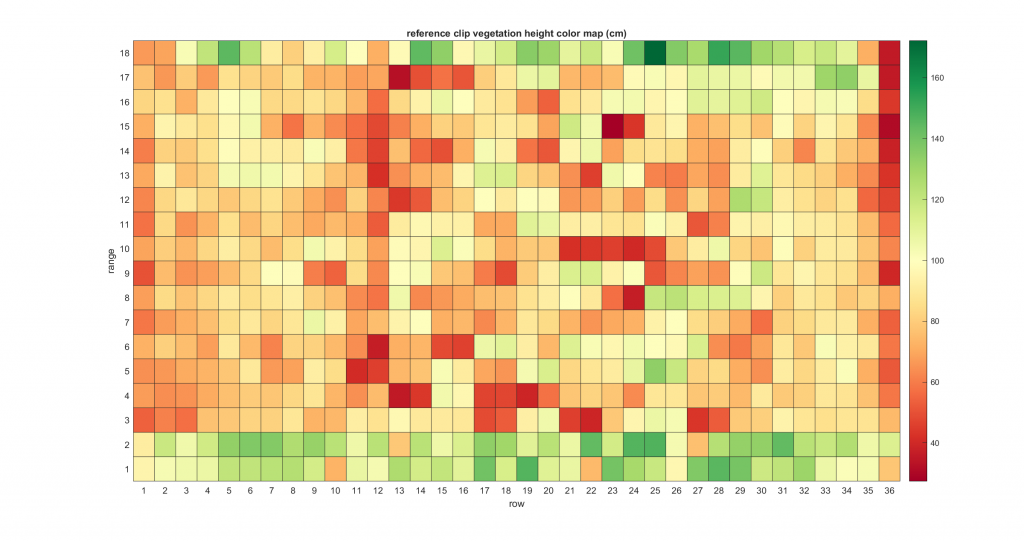

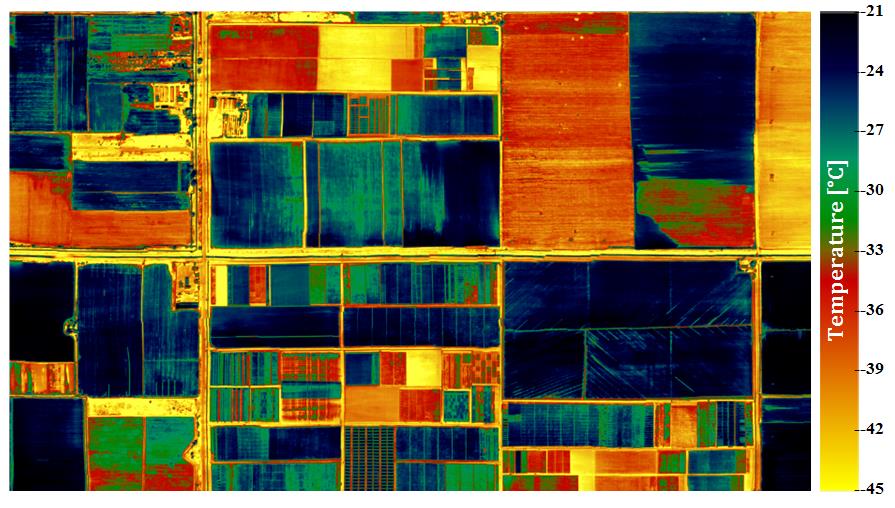

Speed breeding uses artificially-extended daylength, controlled temperatures, genomic selection, data science, artificial intelligence tools and advanced technology for recording plant information — also called phenotyping — to make breeding faster and more efficient. A CIMMYT speed breeding facility for wheat features a screenhouse with specialized lighting, controlled temperatures and other special fixings that will allow four crop cycles — or generations — to be grown per year, in place of only two cycles with normal field trials. Speed breeding facilities will accelerate the development of productive and robust varieties by crop research programs worldwide.

Data analysis and management. Growing and evaluating hundreds of thousands of plants in diverse trials across multiple sites each season generates enormous volumes of data that breeders must examine, integrate, and co-analyze to inform decisions, especially about which lines to cross and which populations to discard or move forward. New informatics tools such as the Enterprise Breeding System will help scientists to manage, analyze and apply big data from genomics, field and lab studies.

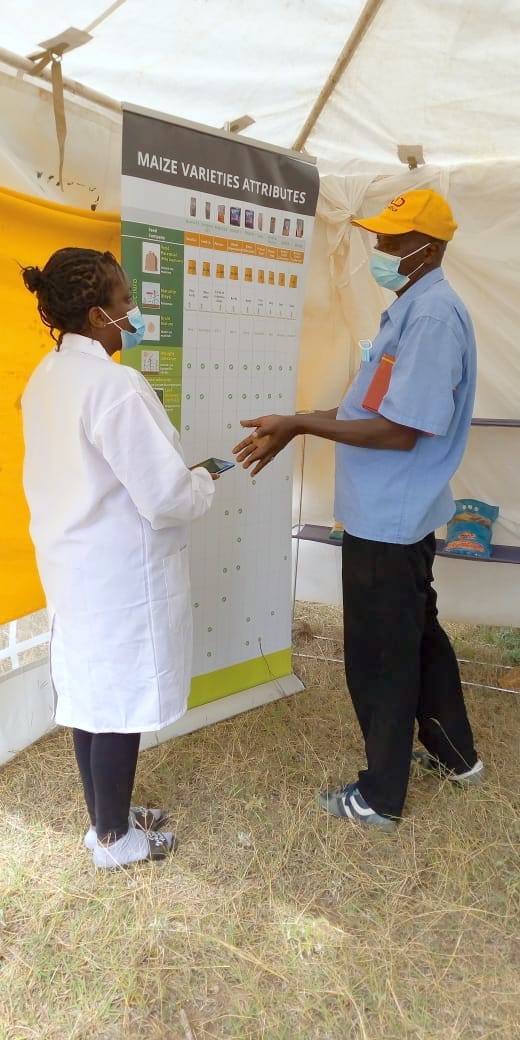

Following the leaders. Driven by competition and the quest for profits, private companies that market seed and other farm products are generally on the cutting edge of breeding innovations. The CGIAR’s Excellence in Breeding (EiB) initiative is helping crop breeding programs that serve farmers in low- and middle-income countries to adopt appropriate best practices from private companies, including molecular marker-based approaches, strategic mechanization, digitization and use of big data to drive decision making. Modern plant breeding begins by ensuring that the new varieties produced are in line with what farmers and consumers want and need.

Cover photo: CIMMYT experimental station in Toluca, Mexico. Located in a valley at 2,630 meters above sea level with a cool and humid climate, it is the ideal location for selecting wheat materials resistant to foliar diseases, such as wheat rust. Conventional plant breeding involves selection among hundreds of thousands of plants from crosses over many generations, and requires extensive and costly field, screenhouse and lab facilities. (Photo: Alfonso Cortés/CIMMYT)