Conservation agriculture expert at Oxford Farming Conference

WHAT: Bram Govaerts, strategic leader for Sustainable Intensification in Latin America and Latin America representative at the Mexico-based International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), will make keynote speech entitled “Ending hunger: Can we achieve humanity’s elusive goal by 2050?” at the Oxford Farming Conference (OFC) at the University of Oxford, in Oxford, UK.

WHEN: Wednesday, January 6, 2016 at 10:30 a.m.

WHERE: South School, Examination Schools, University of Oxford, 75-81 High Street, Oxford, UK, OX1 4AS

ABOUT OFC: The Oxford Farming Conference has been held in Oxford for more than 70 years, attracting strong debate and exceptional speakers.

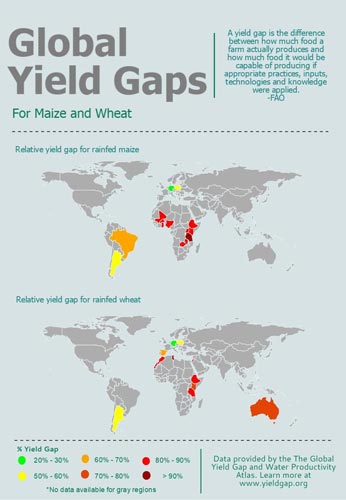

OTHER DETAILS: Bram Govaerts, who will be available for media interviews, will deliver the keynote Frank Parkinson Lecture sponsored by the Frank Parkinson Agricultural Trust, which aims to contribute to the improvement and welfare of British agriculture. The lecture will examine key challenges for achieving food security for a global population of 9.7 billion, which the U.N. projects will have grown 33 percent from a current 7.3 billion people by 2050. Demand for food, driven by population, demographic changes and increasing global wealth will rise more than 60 percent, according to a recent report from the Taskforce on Extreme Weather and Global Food System Resilience. Govaerts will discuss such risks to agricultural production as:

- The need for funding and political will to support technological innovations to improve farming techniques for small landholders in the global south

- How mobile technology could benefit agricultural research, development and relaying innovations to farmers

- Machinery prototypes, which can help transform agricultural practices

- How minimal soil disturbance, permanent soil cover and crop rotation can boost yields, increase profit and protect the environment

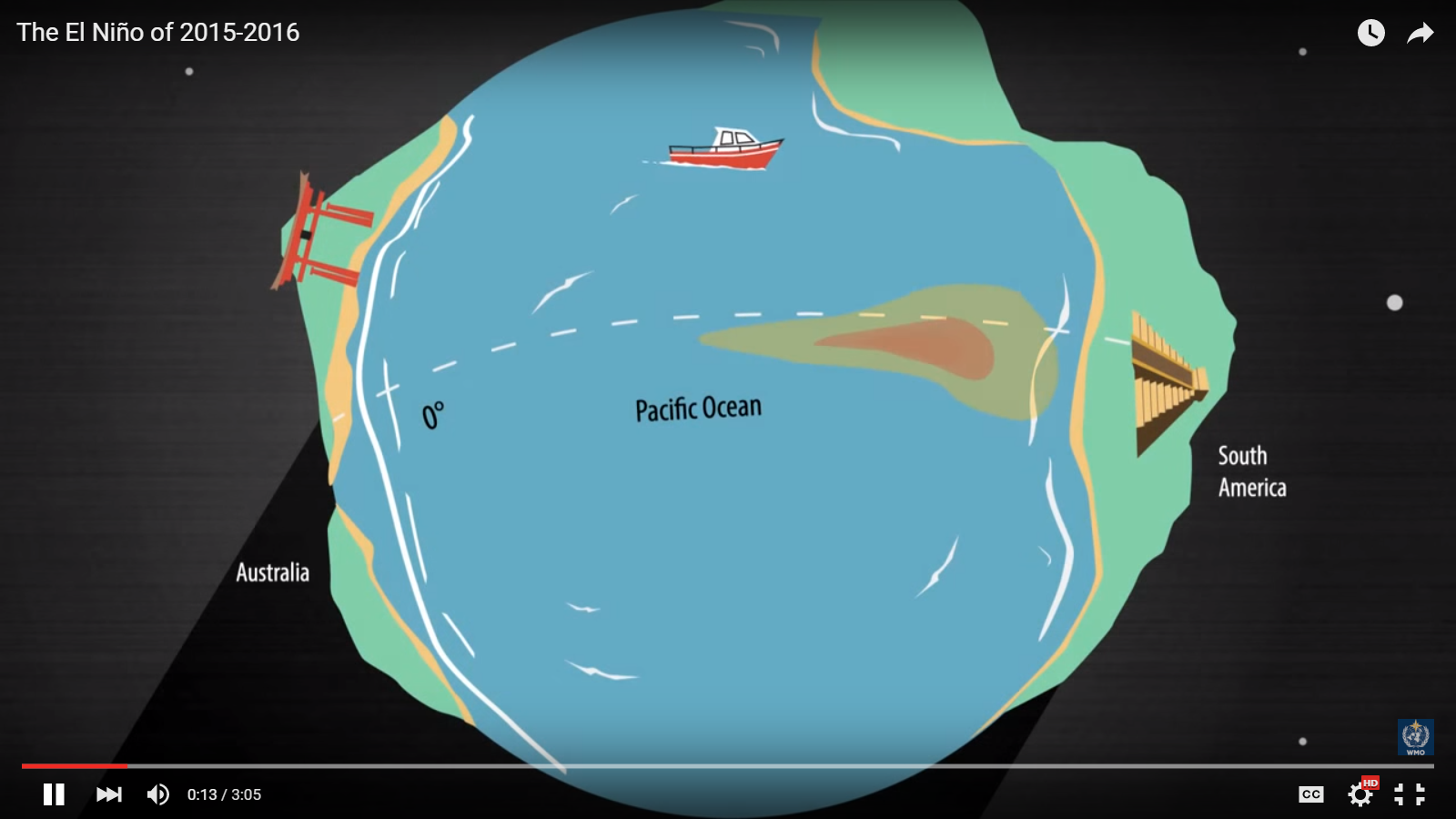

- Climate change: carbon sequestration debate; soil does not sequester the carbon needed to mitigate the impact of climate change as some policy makers suggest

- Climate change: How CIMMYT is working to produce drought and heat tolerant varieties of maize and wheat

- Why women are less likely than men to uptake conservation agricultural practices in developing countries

- How CIMMYT connects smallholder maize farmers in Mexico with top restaurants and chefs in New York City

- The U.N. Sustainable Development Goals: A recipe for success in achieving food security

- MasAgro: Mexico’s Sustainable Modernization of Traditional Agriculture project involving more than 100 organizations, offering training, technical support, seeds

- Dangerous diseases: How CIMMYT is producing varieties resistant to Maize Lethal Necrosis and Tar Spot Complex

MORE INFORMATION:

Julie Mollins, CIMMYT communications, by email at j.mollins@cgiar.org or by mobile at +52 1 595 106 9307 or by Twitter @jmollins or by Skype at juliemollins

Genevieve Renard, head of CIMMYT communications, at g.renard@cgiar.org or +52 1 595 114 9880 or @genevrenard

ABOUT CIMMYT:

CIMMYT, headquartered in El Batan, Mexico, is the global leader in research for development in wheat and maize and wheat- and maize-based farming systems. CIMMYT works throughout the developing world with hundreds of partners to sustainably increase the productivity of maize and wheat systems to improve food security and livelihoods. CIMMYT is a member of the 15-member CGIAR Consortium and leads the Consortium Research Programs on Wheat and Maize. CIMMYT receives support from national governments, foundations, development banks and other public and private agencies.

CIMMYT website: http://staging.cimmyt.org

CGIAR website: http://www.cgiar.org

BACKGROUND:

Frank Parkinson Agricultural Trust

United Nations population projections

Taskforce on Extreme Weather and Global Food System Resilience

Q+A: Young scientist wins award for “taking it to the farmer”

Gender bias may limit uptake of climate-smart farm practices, study shows

Race for food security can be won, Mexico agriculture secretary says

Global conference underscores complex socio-economic role of wheat

Click here to follow Bram Govaerts on Twitter

A

A

Jennifer Johnson

Jennifer Johnson