Retrospective quantitative genetic analysis and genomic prediction of global wheat yields

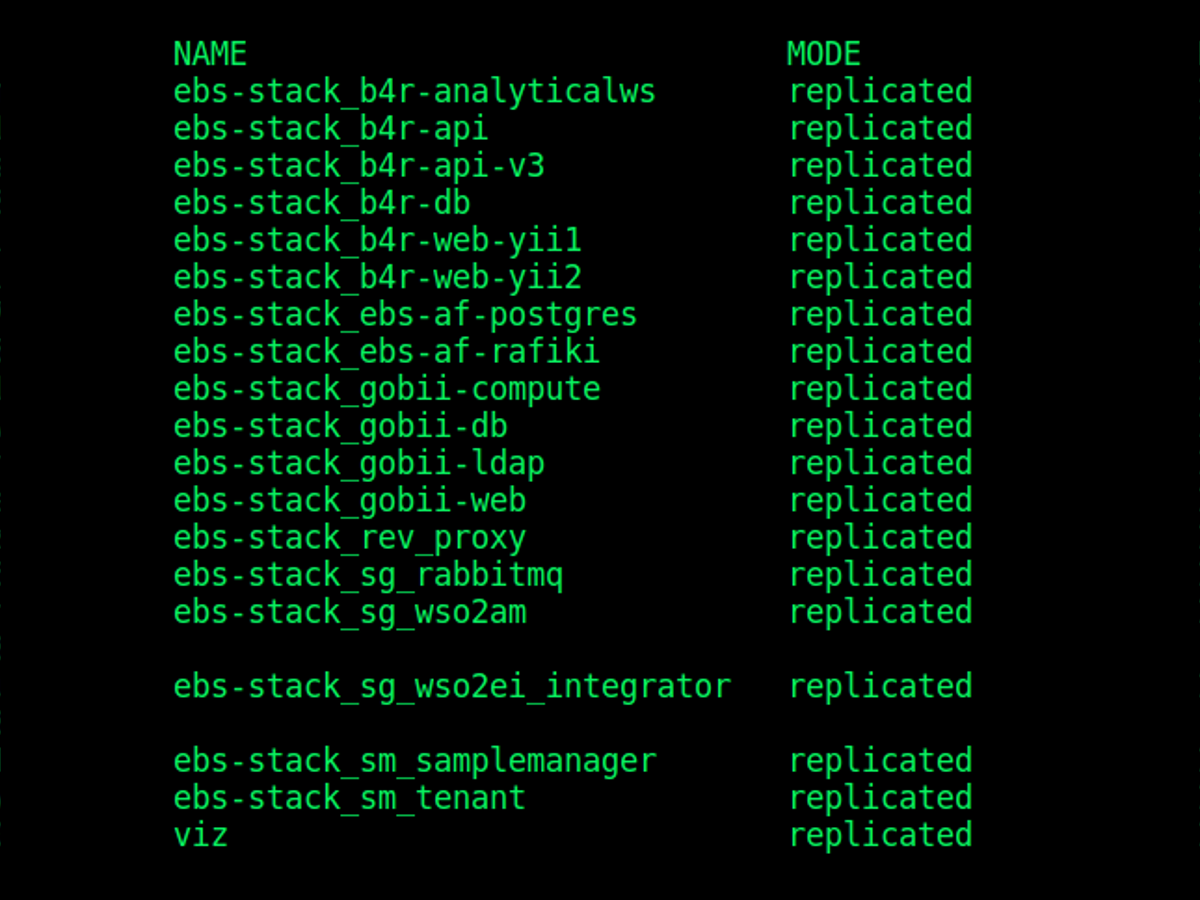

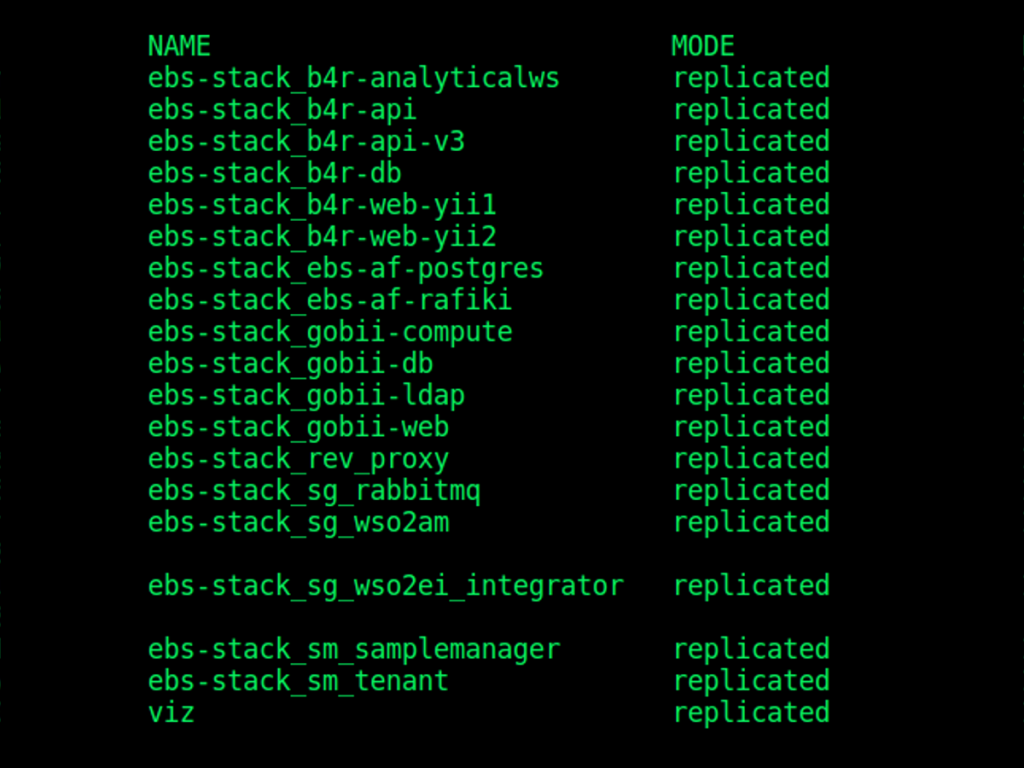

The process for breeding for grain yield in bread wheat at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) involves three-stage testing at an experimental station in the desert environment of Ciudad Obregón, in Mexico’s Yaqui Valley. Because the conditions in Obregón are extremely favorable, CIMMYT wheat breeders are able to replicate growing environments all over the world and test the yield potential and climate-resilience of wheat varieties for every major global wheat growing area. These replicated test areas in Obregón are known as selection environments (SEs).

This process has its roots in the innovative work of wheat breeder and Nobel Prize winner Norman Borlaug, more than 50 years ago. Wheat scientists at CIMMYT, led by wheat breeder Philomin Juliana, wanted to see if it remained effective.

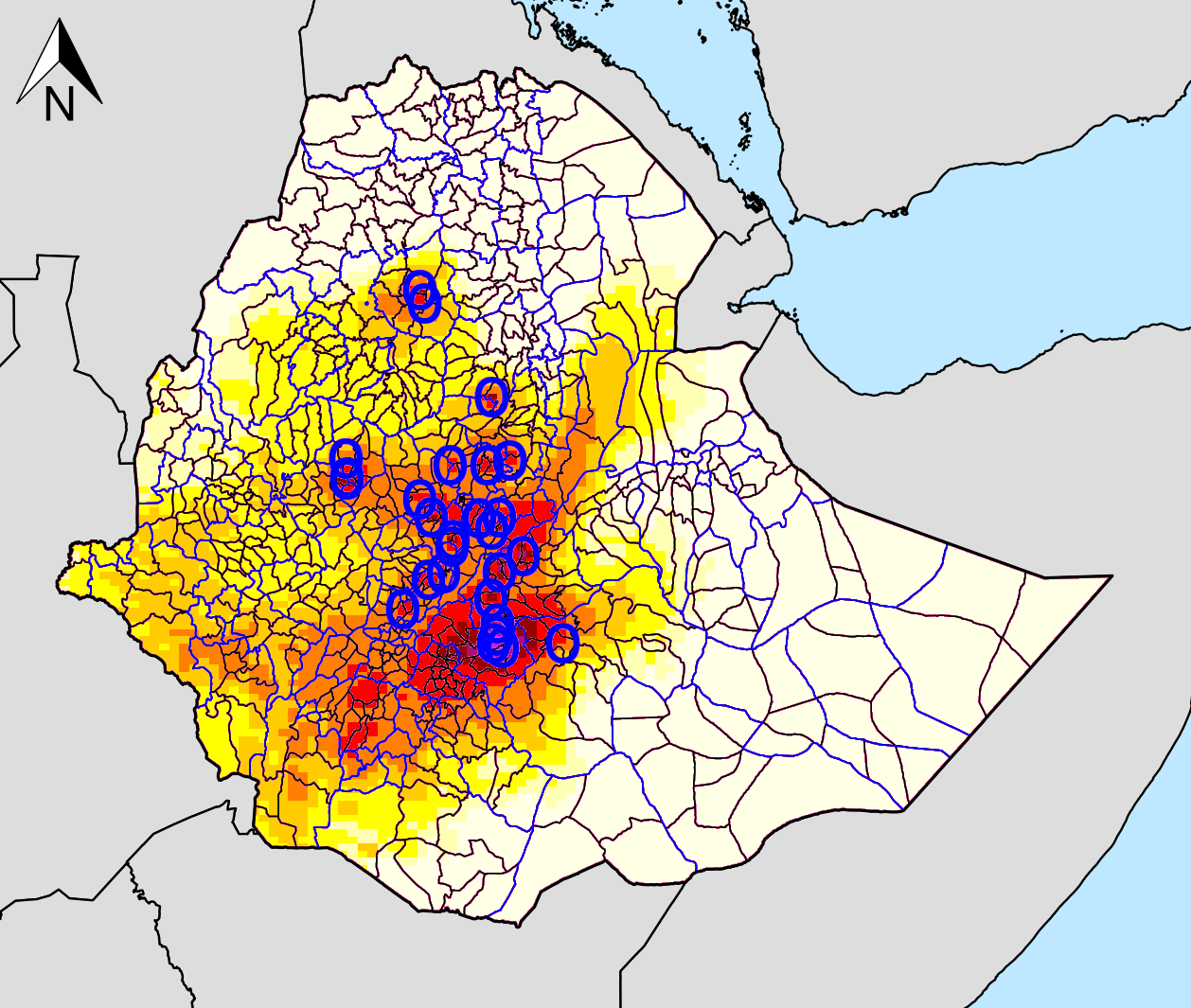

The scientists conducted a large quantitative genetics study comparing the grain yield performance of lines in the Obregón SEs with that of lines in target growing sites throughout the world. They based their comparison on data from two major wheat trials: the South Asia Bread Wheat Genomic Prediction Yield Trials in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh initiated by the U.S. Agency for International Development Feed the Future initiative and the global testing environments of the Elite Spring Wheat Yield Trials.

The findings, published in Retrospective Quantitative Genetic Analysis and Genomic Prediction of Global Wheat Yields, in Frontiers in Plant Science, found that the Obregón yield testing process in different SEs is very efficient in developing high-yielding and resilient wheat lines for target sites.

The authors found higher average heritabilities, or trait variations due to genetic differences, for grain yield in the Obregón SEs than in the target sites (44.2 and 92.3% higher for the South Asia and global trials, respectively), indicating greater precision in the SE trials than those in the target sites. They also observed significant genetic correlations between one or more SEs in Obregón and all five South Asian sites, as well as with the majority (65.1%) of the Elite Spring Wheat Yield Trial sites. Lastly, they found a high ratio of selection response by selecting for grain yield in the SEs of Obregón than directly in the target sites.

“The results of this study make it evident that the rigorous multi-year yield testing in Obregón environments has helped to develop wheat lines that have wide-adaptability across diverse geographical locations and resilience to environmental variations,” said Philomin Juliana, CIMMYT associate scientist and lead author of the article.

“This is particularly important for smallholder farmers in developing countries growing wheat on less than 2 hectares who cannot afford crop losses due to year-to-year environmental changes.”

In addition to these comparisons, the scientists conducted genomic prediction for grain yield in the target sites, based on the performance of the same lines in the SEs of Obregón. They found high year-to-year variations in grain yield predictabilities, highlighting the importance of multi-environment testing across time and space to stave off the environment-induced uncertainties in wheat yields.

“While our results demonstrate the challenges involved in genomic prediction of grain yield in future unknown environments, it also opens up new horizons for further exciting research on designing genomic selection-driven breeding for wheat grain yield,” said Juliana.

This type of quantitative genetics analysis using multi-year and multi-site grain yield data is one of the first steps to assessing the effectiveness of CIMMYT’s current grain yield testing and making recommendations for improvement—a key objective of the new Accelerating Genetic Gains in Maize and Wheat for Improved Livelihoods (AGG) project, which aims to accelerate the breeding progress by optimizing current breeding schemes.

This work was made possible by the generous support of the Delivering Genetic Gain in Wheat (DGGW) project funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) and managed by Cornell University; the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Feed the Future initiative; and several collaborating national partners who generated the grain yield data.

Read the full article: Retrospective Quantitative Genetic Analysis and Genomic Prediction of Global Wheat Yields

This story was originally posted on the website of the CGIAR Research Program on Wheat (wheat.org).

Cover photo: Wheat fields at CIMMYT’s Campo Experimental Norman E. Borlaug (CENEB) in Ciudad Obregón, Mexico. (Photo: CIMMYT)