June, 2005

What role do farmers play in the evolution of maize diversity? How extensive are the farming networks and other social systems that influence gene flow? These and other questions are helping researchers to combine knowledge of the genetic behavior of plants with information on human behavior to understand the many factors that affect maize diversity.

What role do farmers play in the evolution of maize diversity? How extensive are the farming networks and other social systems that influence gene flow? These and other questions are helping researchers to combine knowledge of the genetic behavior of plants with information on human behavior to understand the many factors that affect maize diversity.

Outside a straw and mud-walled house in rural Hidalgo, Mexico, with chickens walking around and the smell of the cooking fire wafting through the air, CIMMYT researcher Dagoberto Flores drew lines with a stick in the red earth as he explained to a farmer’s wife how maize seed should be planted for an experiment. Along with CIMMYT researcher Alejandro Ramírez, Flores was distributing improved seed in communities where they had conducted surveys for a study on gene flow.

The movement of genes between populations, or gene flow, happens when individuals from different populations cross with each other. CIMMYT social scientist Mauricio Bellon is leading a study that aims to find out the impact of farmers’ practices on gene flow and on the genetic structure of landraces. It will document how practices differ across farming systems, analyze their determinants, figure out how much farmers control gene flow, and explore gene flow’s impacts on maize fitness and diversity and on farmers’ livelihoods.

The farmers visited by Flores and Ramírez in early June near Huatzalingo and Tlaxcoapan, Hidalgo are from just 2 of 20 study communities spanning ecologies from Mexico’s highlands down to the lowlands. Six months earlier, when farmers in these communities responded to researchers’ survey question, they asked some questions of their own: What does CIMMYT do? How can we get seed?

The farmers visited by Flores and Ramírez in early June near Huatzalingo and Tlaxcoapan, Hidalgo are from just 2 of 20 study communities spanning ecologies from Mexico’s highlands down to the lowlands. Six months earlier, when farmers in these communities responded to researchers’ survey question, they asked some questions of their own: What does CIMMYT do? How can we get seed?

The team made it a priority to give the farmers what they requested for free. They drove around in a pick-up truck with seed they had acquired from CIMMYT scientists. They brought black, white, and yellow varieties that were native to the area and had been improved with weevil and drought resistance, and they also brought three CIMMYT varieties that were well adapted to a similar environment in Morelos, Mexico. They explained to the farmers how each variety should be planted in separate squares to facilitate pure seed selection.

“It’s a way to thank them, to bring something back to the communities,” says Bellon. Bringing improved germplasm for experimentation to interested small-scale farmers also allows researchers to get feedback in a more systematic way. The farmers will produce the maize independently, and they can save or discard seed from whichever varieties they choose. The team also distributed seed to farmers in Veracruz, and they plan to return after flowering and at harvest time to see how the improved seed fares compared with native varieties. That component of the project could be the beginning of further research in collaboration with farmers.

Farmers in the survey area of rural Hidalgo grow maize on the poorest, most steeply sloping land and struggle with soil diseases, low soil fertility, leaf diseases, low grain prices, and limited information about the use of chemical herbicides. Strong wind, rain, and hurricanes damage crops. Landslides cause erosion. Some farmers have access to roads and can transport their harvest by vehicle, but some farms located far from the communities have no highway access. The paths to farmers’ fields can be so narrow that not even cargo animals can maneuver on them with loads, so farmers must carry the harvest on their backs. Some walk 10 kilometers up and down slopes with heavy bags on their backs.

Farmers in the survey area of rural Hidalgo grow maize on the poorest, most steeply sloping land and struggle with soil diseases, low soil fertility, leaf diseases, low grain prices, and limited information about the use of chemical herbicides. Strong wind, rain, and hurricanes damage crops. Landslides cause erosion. Some farmers have access to roads and can transport their harvest by vehicle, but some farms located far from the communities have no highway access. The paths to farmers’ fields can be so narrow that not even cargo animals can maneuver on them with loads, so farmers must carry the harvest on their backs. Some walk 10 kilometers up and down slopes with heavy bags on their backs.

Many people grew coffee around Huatzalingo until about 10 years ago when the price plummeted. A kilogram of coffee used to fetch a price of about 20 pesos, or US$ 2. Now it fetches about five pesos, or 50 cents, per kilo, and even less during harvest time when the crop is abundant. Coffee producers in the area receive average government subsidies of between 125 and 300 pesos, or between US$ 10-30. One effect of the price drop has been increased immigration to Mexico City, to the city of Reynosa near the US border, and to lowland areas where orange cultivation is booming.

Partly in response to the crisis, farmers have started diversifying into alternative crops such as vanilla, citrus fruits, bananas, sugar cane, sesame, beans, chayote, chili peppers, and lentils, but the poor soils do not favor more lucrative crops. Maize is still the most important agricultural product in people’s diets in this area, and farmers grow it primarily for family consumption. They exchange seed with friends, neighbors, and producers in nearby communities, and they have conserved diverse native varieties.

In Mexico, maize has such great genetic diversity because farmers’ practices encourage the further evolution of maize landraces. Maize was domesticated about 6,000 years ago within the current borders of Mexico. Farmers created a variety of races to fit different needs by mixing different maize types, and they still experiment like that to this day. They save seed between seasons and trade seed with each other, and the wind carries pollen between different cultivars to create new mixtures.

“They are not artifacts in a museum,” Bellon says about landraces. “They are changing, they are moving.” Seed selection has a great impact on gene flow. Poor farmers typically exchange seed with each other, but little has been documented about the social relations that drive seed systems. With growing concerns about a loss of crop genetic diversity and a need to conserve genetic resources in recent years, it is important to understand the social principles of seed flow (and ultimately gene flow) in Mexico. The study findings will assist in exploration of the potential impact of transgenes. The researchers will develop models to try to predict how a transgene would diffuse and behave after it has been in a population for 10 or 20 years.

By learning about the relationships between farmers’ practices and gene flow, researchers hope to promote more effective policies regarding the conservation of diversity in farmers’ fields, the distribution of improved germplasm, and transgene management. Funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, the study combines social science with genetics to connect social and biological factors in maize varieties. Molecular markers will help show how much gene flow has occurred over time between the Mexican highlands and lowlands.

Researchers used geographic information systems to choose varied environments for the survey. Starting in October 2003, they sampled maize populations and interviewed the male and female heads of 20 households in each community for a total of 800 intensive interviews in 400 households. They asked about topics such as principal crops, planting cycles and methods, maize varieties, machinery and tools, infrastructure, language, seed selection, fertilizer, pest and weed control, plant height, harvest, transportation, production problems, maize uses, the sale and demand of different varieties, knowledge about maize reproduction, husk commercialization, and level of migration.

Preliminary findings have already surprised Bellon. A growing market for maize husks, which are used to wrap traditional foods such as tamales, is changing the economics of maize production. Owing to increasing demand from the US, husks have become more commercially important and profitable than grain in some communities. Facing abysmally low grain prices, the success of husk production has caused some producers to seek maize varieties with high quality husks, almost regardless of grain quality.

Bellon was also surprised at the lack of improved varieties in the areas they studied. Farmers tended to seek out and plant native varieties instead of hybrids. Some farmers thought hybrids were expensive, produced poor quality husks, and required good land, chemicals, and fertilizer, but they thought native varieties adapted easily to marginal local conditions.

The study grew out of a six-year project in Oaxaca that examined the relationship between farmers’ practices and the genetic structure of maize landraces and seed flow among farmers. It also explored the implications of transgenic technologies. However, while the Oaxaca project examined a few communities located in one environment, the idea with this follow-up study was to examine many locations in the same and different environments. In that way researchers can find out if gene flow is localized or if it crosses between regional environments. “It’s the same research model on a broader scale,” says Bellon.

For information: Mauricio Bellon

Erginbas is just beginning work on a project to screen wheat for resistance to a disease called crown rot. It is caused by a microscopic fungus in the soil called Fusarium culmorum (related to but not the same as the Fusarium fungus that causes head blight in wheat) and can cause farmers serious loss of yield. Her first tests have been with plants grown in a greenhouse on the station. Later she will expand her work to the field and as part of her program will spend some time in Australia with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO). Since there is some evidence that the fungus that causes crown rot can survive for up to two years in crop residues, there is a great interest in this work as more farmers adopt reduced tillage and stubble retention on their land.

Erginbas is just beginning work on a project to screen wheat for resistance to a disease called crown rot. It is caused by a microscopic fungus in the soil called Fusarium culmorum (related to but not the same as the Fusarium fungus that causes head blight in wheat) and can cause farmers serious loss of yield. Her first tests have been with plants grown in a greenhouse on the station. Later she will expand her work to the field and as part of her program will spend some time in Australia with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO). Since there is some evidence that the fungus that causes crown rot can survive for up to two years in crop residues, there is a great interest in this work as more farmers adopt reduced tillage and stubble retention on their land. These pathogens are especially damaging when wheat is grown under more marginal conditions, and so the work in Turkey that these two young students are doing may have its greatest impact where farmers struggle the most.

These pathogens are especially damaging when wheat is grown under more marginal conditions, and so the work in Turkey that these two young students are doing may have its greatest impact where farmers struggle the most. A radio program in Nepal brings information to farmers in a language they understand.

A radio program in Nepal brings information to farmers in a language they understand.

Improved maize makes a big difference in the lives of smallholder farmers on the slopes of Mt Kenya.

Improved maize makes a big difference in the lives of smallholder farmers on the slopes of Mt Kenya.

In March, CIMMYT scientists continued their pursuit of drought tolerant wheat with the second field trial of transgenic lines carrying the DREB gene, given to CIMMYT by Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences

In March, CIMMYT scientists continued their pursuit of drought tolerant wheat with the second field trial of transgenic lines carrying the DREB gene, given to CIMMYT by Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences  This second trial narrows the focus of investigation to four transgenic lines and uses a larger plot to ensure better control and analysis. It will also expose the experimental lines and control plants to both watered and drought conditions to determine their respective performance.

This second trial narrows the focus of investigation to four transgenic lines and uses a larger plot to ensure better control and analysis. It will also expose the experimental lines and control plants to both watered and drought conditions to determine their respective performance. Farmers and community leaders in Kenya’s most densely-populated region have organized to produce and sell seed of a maize variety so well-suited for smallholders that distant peers in highland Nepal have also selected it.

Farmers and community leaders in Kenya’s most densely-populated region have organized to produce and sell seed of a maize variety so well-suited for smallholders that distant peers in highland Nepal have also selected it.

An important component of a current ACIAR-funded project (“Wheat and Maize Productivity Improvement in Afghanistan”) has included collaborative work with farmers and non-government and international organizations to verify in farmers’ fields the performance and acceptability of improved wheat and maize varieties. For wheat, the project uses two approaches:

An important component of a current ACIAR-funded project (“Wheat and Maize Productivity Improvement in Afghanistan”) has included collaborative work with farmers and non-government and international organizations to verify in farmers’ fields the performance and acceptability of improved wheat and maize varieties. For wheat, the project uses two approaches:

A new DNA detection service provided by CIMMYT and KARI responds to African researchers’ calls for modern technology.

A new DNA detection service provided by CIMMYT and KARI responds to African researchers’ calls for modern technology. CIMMYT maize helps villagers quadruple their yields.

CIMMYT maize helps villagers quadruple their yields.

CIMMYT’s biometrics team receives special recognition for advancing the science behind crop genetic resource conservation.

CIMMYT’s biometrics team receives special recognition for advancing the science behind crop genetic resource conservation.

Young Indonesian researchers are reaping the benefits of collaboration with CIMMYT and at the same time helping farmers in their country.

Young Indonesian researchers are reaping the benefits of collaboration with CIMMYT and at the same time helping farmers in their country. “This is the untold story of the quiet biotech revolution going on in maize breeding in Asia,” says CIMMYT’s Luz George. “It is a successful transfer of technology from CIMMYT to developing countries which has now found direct application in the work of national program maize breeders.”

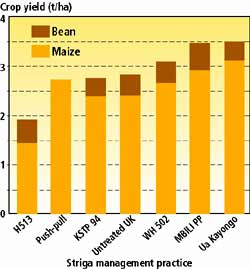

“This is the untold story of the quiet biotech revolution going on in maize breeding in Asia,” says CIMMYT’s Luz George. “It is a successful transfer of technology from CIMMYT to developing countries which has now found direct application in the work of national program maize breeders.” Kenyan farmers’ verdict is out: “Ua Kayongo is the best Striga control practice and we will adopt it.”

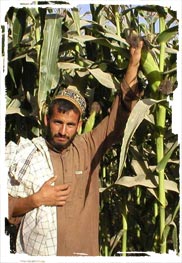

Kenyan farmers’ verdict is out: “Ua Kayongo is the best Striga control practice and we will adopt it.” Farmers in the WeRATE evaluations were able to plant the new maize using their normal husbandry methods, including intercropping with legumes and root crops. “I’ve been pulling and burying Striga on my 5-acre farm for the past 17 years and the problem has only grown worse,” said Rose Katete, a farmer from Teso; “Ua Kayongo has provided the best crop of maize that I’ve ever grown!”

Farmers in the WeRATE evaluations were able to plant the new maize using their normal husbandry methods, including intercropping with legumes and root crops. “I’ve been pulling and burying Striga on my 5-acre farm for the past 17 years and the problem has only grown worse,” said Rose Katete, a farmer from Teso; “Ua Kayongo has provided the best crop of maize that I’ve ever grown!” What role do farmers play in the evolution of maize diversity? How extensive are the farming networks and other social systems that influence gene flow? These and other questions are helping researchers to combine knowledge of the genetic behavior of plants with information on human behavior to understand the many factors that affect maize diversity.

What role do farmers play in the evolution of maize diversity? How extensive are the farming networks and other social systems that influence gene flow? These and other questions are helping researchers to combine knowledge of the genetic behavior of plants with information on human behavior to understand the many factors that affect maize diversity. The farmers visited by Flores and Ramírez in early June near Huatzalingo and Tlaxcoapan, Hidalgo are from just 2 of 20 study communities spanning ecologies from Mexico’s highlands down to the lowlands. Six months earlier, when farmers in these communities responded to researchers’ survey question, they asked some questions of their own: What does CIMMYT do? How can we get seed?

The farmers visited by Flores and Ramírez in early June near Huatzalingo and Tlaxcoapan, Hidalgo are from just 2 of 20 study communities spanning ecologies from Mexico’s highlands down to the lowlands. Six months earlier, when farmers in these communities responded to researchers’ survey question, they asked some questions of their own: What does CIMMYT do? How can we get seed? Farmers in the survey area of rural Hidalgo grow maize on the poorest, most steeply sloping land and struggle with soil diseases, low soil fertility, leaf diseases, low grain prices, and limited information about the use of chemical herbicides. Strong wind, rain, and hurricanes damage crops. Landslides cause erosion. Some farmers have access to roads and can transport their harvest by vehicle, but some farms located far from the communities have no highway access. The paths to farmers’ fields can be so narrow that not even cargo animals can maneuver on them with loads, so farmers must carry the harvest on their backs. Some walk 10 kilometers up and down slopes with heavy bags on their backs.

Farmers in the survey area of rural Hidalgo grow maize on the poorest, most steeply sloping land and struggle with soil diseases, low soil fertility, leaf diseases, low grain prices, and limited information about the use of chemical herbicides. Strong wind, rain, and hurricanes damage crops. Landslides cause erosion. Some farmers have access to roads and can transport their harvest by vehicle, but some farms located far from the communities have no highway access. The paths to farmers’ fields can be so narrow that not even cargo animals can maneuver on them with loads, so farmers must carry the harvest on their backs. Some walk 10 kilometers up and down slopes with heavy bags on their backs.