Stepping up the fight against maize lethal necrosis in Eastern Africa

“I can now identify with accuracy plants affected with maize lethal necrotic disease,” stated Regina Tende, PhD student attached to CIMMYT, after attending the CIMMYT-Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (KARI) “Identification and Management of Maize Lethal Necrosis” workshop in Narok, Kenya, during 30 June-3 July 2013. This was not the case a few weeks ago when Tende, who is also a senior research officer at KARI-Katumani, received leaf samples from a farmer for maize lethal necrosis (MLN) verification.

“I can now identify with accuracy plants affected with maize lethal necrotic disease,” stated Regina Tende, PhD student attached to CIMMYT, after attending the CIMMYT-Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (KARI) “Identification and Management of Maize Lethal Necrosis” workshop in Narok, Kenya, during 30 June-3 July 2013. This was not the case a few weeks ago when Tende, who is also a senior research officer at KARI-Katumani, received leaf samples from a farmer for maize lethal necrosis (MLN) verification.

Tende is one of many scientists and technicians who experienced difficulty in differentiating MLN from other diseases or abiotic stresses with similar symptoms. According to Stephen Mugo, CIMMYT Global Maize Program (GMP) principal scientist and organizer of the workshop, this difficulty encouraged CIMMYT and KARI to organize this event to raise awareness about MLN among scientists, technicians, and skilled field staff; provide training on MLN diagnosis especially at field nurseries, trials, and seed production fields; train on MLN severity scoring to improve the quality of data generation in screening trials; and introduce MLN management in field screening sites to scientists, technicians, and skilled staff. The workshop brought together over 80 scientists and technicians from CIMMYT, KARI, and other national agricultural research systems (NARS) partners from Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe.

“It is important that all the people on the ground, particularly the technicians who interact daily with the plants and supervise research activities at the stations, understand the disease, are able to systematically scout for it, and have the ability to spot it out from similar symptomatic diseases and conditions like nutrient deficiency,” stated GMP director B.M. Prasanna.

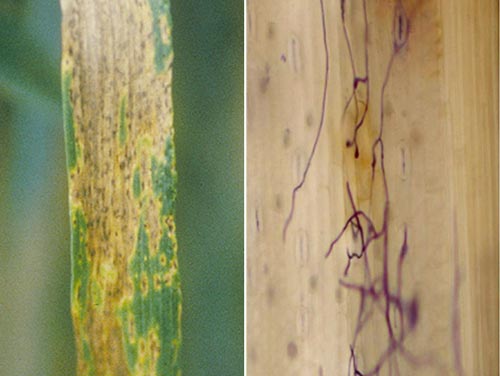

Proper and timely identification of the MLN disease, which is a pre-requisite for effective control, is not easy. CIMMYT maize breeder Biswanath Das explains: “First of all, the disease is caused by a combination of two viruses, Maize chlorotic mottle virus (MCMV) and Sugarcane mosaic virus (SCMV). Secondly, its symptoms –severe mottling of leaves, dead heart, stunted growth (shortened internode distance), leaf necrosis, sterility, poor seed set, shriveled seeds– are not always unique to MLN but could be due to other fungal diseases and abiotic conditions.” The training workshop was one of CIMMYT/KARI initiatives to combat the disease threatening all the gains made so far in maize breeding. “With nearly 99% of the commercial maize varieties so far released in Kenya being susceptible to MLN, it is important that institutions like CIMMYT and KARI, in strong collaboration with the seed sector, develop and deploy MLN disease resistant varieties in an accelerated manner,” stated Prasanna. One of the key initiatives in this fight is the establishment of a centralized MLN screening facility under artificial inoculation for Eastern Africa at the KARI Livestock Research Farm in Naivasha. Plans are also underway to establish a network of MLN testing sites (under natural disease pressure) in the region to evaluate promising materials from artificial inoculation trials in Naivasha. The state of the art maize doubled haploid (DH) facility currently under construction in Kiboko will also play a crucial role in accelerating MLN resistant germplasm development. “The DH technology, in combination with molecular markers, can help reduce by half the time taken for developing MLN resistant versions of existing elite susceptible lines,” stated Prasanna.

During his opening speech, Joseph Ng’etich, deputy director of Crop Protection, Ministry of Agriculture, noted that about 26,000 hectares of maize in Kenya were affected in 2012, resulting in an estimated loss of 56,730 tons, valued at approximately US$ 23.5 million. Seed producers also lost significant acreages of pre-basic seed in 2012: Agriseed lost 10 acres in Narok; Kenya Seed lost 75; and Monsanto 20 at Migtyo farm in Baringo, according to Dickson Ligeyo, KARI senior research officer and head of Maize Working Group in Kenya.

During his opening speech, Joseph Ng’etich, deputy director of Crop Protection, Ministry of Agriculture, noted that about 26,000 hectares of maize in Kenya were affected in 2012, resulting in an estimated loss of 56,730 tons, valued at approximately US$ 23.5 million. Seed producers also lost significant acreages of pre-basic seed in 2012: Agriseed lost 10 acres in Narok; Kenya Seed lost 75; and Monsanto 20 at Migtyo farm in Baringo, according to Dickson Ligeyo, KARI senior research officer and head of Maize Working Group in Kenya.

While this loss represents only 1.7%, Ligeyo assured everyone that Kenya is not taking any chances and has come up with a raft of measures and recommendations: farmers in areas where rainfall is all year round or maize is produced under irrigation are advised to plant maize only once a year; local quarantine has been enforced and farmers are to remove all infected materials from the fields and stop all movement of green maize from affected to non-affected areas; seed companies must ensure that seeds are treated with appropriate seed dressers at recommended rates, they must also promote good agricultural practices, crop diversification, and rotation with non-cereal crops.

Throughout the workshop, participants learned about theoretical aspects of MLN, such as the disease dynamics, management of MLN trials and nurseries, and identification of germplasm for resistance to MLN. They also participated in practical sessions on artificial inoculation, and identification and scoring. Several CIMMYT scientists played an active role in organizing the workshop, including breeders Stephen Mugo, Biswanath Das, Yoseph Beyene, and Lewis Machida; entomologist Tadele Tefera; and seed systems specialist Mosisa Regasa. They were accompanied by KARI scientist Bramwel Wanjala, KEPHIS regulatory officer Florence Munguti, and NARS maize research leaders Claver Ngaboyisonga (Rwanda), Dickson Ligeyo (Kenya), Julius Serumaga (Uganda), and Kheri Kitenge (Tanzania). During his closing remarks, KARI Food Crops program officer Raphael Ngigi, on behalf of KARI director, urged participants to rigorously implement what they had learnt during the workshop in their respective countries or Kenya regions to help combat MLN at both research farms and farmers’ fields.

Commenting on the usefulness of the workshop, technical officer at KARI-Embu Fred Manyara stated: “I will no longer say I do not know or I am not sure, when confronted by a farmer’s question on MLN.”

After screening some 500 wheat lines and varieties at 6 sites in Bangladesh, India, and Nepal, a group of scientists were able to identify 35 genotypes that resist spot blotch. This is the number-one disease of wheat in the Eastern Gangetic Plains, seriously damaging the crops of farmers—who are mostly smallholders—on some 9 million hectares.

After screening some 500 wheat lines and varieties at 6 sites in Bangladesh, India, and Nepal, a group of scientists were able to identify 35 genotypes that resist spot blotch. This is the number-one disease of wheat in the Eastern Gangetic Plains, seriously damaging the crops of farmers—who are mostly smallholders—on some 9 million hectares. Hot models were the main topic of conversation at El Batan during 19-21 June 2013, when international experts from 18 leading research institutions participated in a workshop on “Modeling Wheat Responses to High Temperature.”

Hot models were the main topic of conversation at El Batan during 19-21 June 2013, when international experts from 18 leading research institutions participated in a workshop on “Modeling Wheat Responses to High Temperature.” After months of discussions and debates on the scientific evidence regarding conservation agriculture for small-scale, resource-poor farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, a group of 40 scientists reached a consensus on the goals of conservation agriculture and the research necessary to reach these goals. The discussions leading to the signing of the

After months of discussions and debates on the scientific evidence regarding conservation agriculture for small-scale, resource-poor farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, a group of 40 scientists reached a consensus on the goals of conservation agriculture and the research necessary to reach these goals. The discussions leading to the signing of the  The maize lethal necrosis (MLN) disease first appeared in Kenya’s Rift Valley in 2011 and quickly spread to other parts of Kenya, as well as to Uganda and Tanzania. Caused by a synergistic interplay of maize chlorotic mottle virus (MCMV) and any of the cereal viruses in the family, Potyviridae, such as Sugarcane mosaic virus (SCMV), Maize dwarf mosaic virus (MDMV), or Wheat streak mosaic virus (WSMV), MLN can cause total crop loss if not controlled effectively.

The maize lethal necrosis (MLN) disease first appeared in Kenya’s Rift Valley in 2011 and quickly spread to other parts of Kenya, as well as to Uganda and Tanzania. Caused by a synergistic interplay of maize chlorotic mottle virus (MCMV) and any of the cereal viruses in the family, Potyviridae, such as Sugarcane mosaic virus (SCMV), Maize dwarf mosaic virus (MDMV), or Wheat streak mosaic virus (WSMV), MLN can cause total crop loss if not controlled effectively.

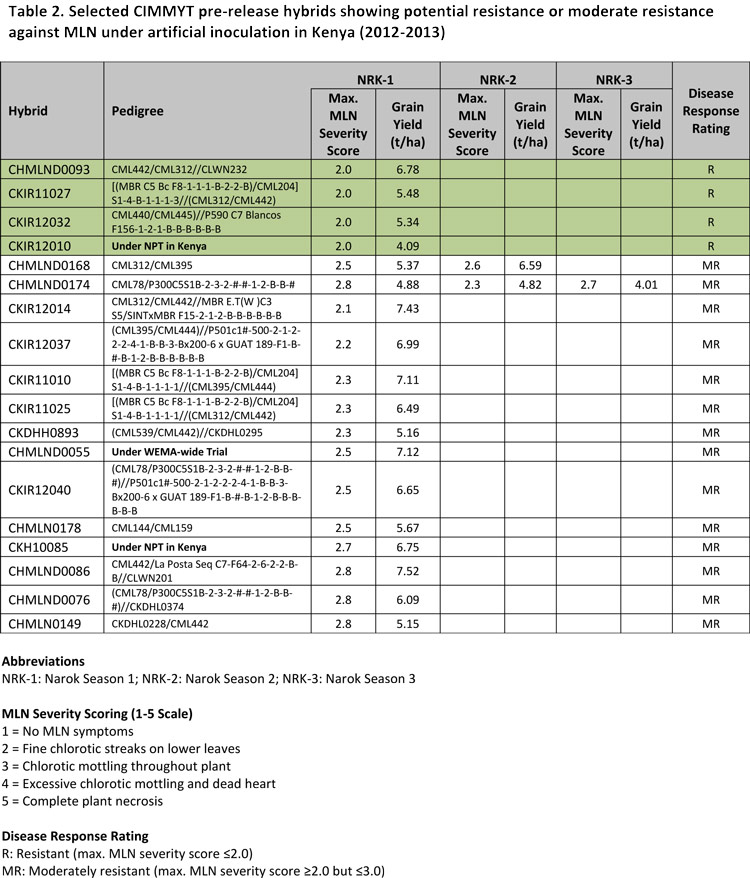

Download table in pdf format

Download table in pdf format On 26-27 April 2013, the

On 26-27 April 2013, the  The project has generally been considered very successful. “We now know which mycotoxins are important in the region and we have the products to potentially minimize the risk,” commented Mahuku. “What we need is to widely test and disseminate the products so that they reach as many farmers as possible. With a little infusion of resources, the dedication demonstrated by this group, and support from policy makers, I have no doubt that we will get there.”

The project has generally been considered very successful. “We now know which mycotoxins are important in the region and we have the products to potentially minimize the risk,” commented Mahuku. “What we need is to widely test and disseminate the products so that they reach as many farmers as possible. With a little infusion of resources, the dedication demonstrated by this group, and support from policy makers, I have no doubt that we will get there.”

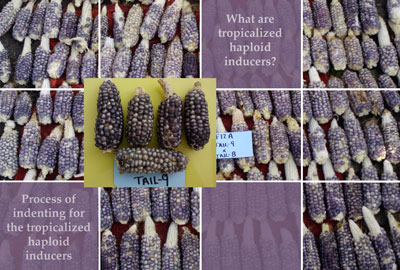

The doubled haploid (DH) technology enables rapid development of completely homozygous maize lines and offers significant opportunities for fast-track development and release of elite cultivars. Besides simplified logistics and reduced costs, use of DH lines in conjunction with molecular markers significantly improves genetic gains and breeding efficiency. DH lines also are valuable tools in marker-trait association studies, molecular marker-assisted or genomic selection-based breeding, and functional genomics.

The doubled haploid (DH) technology enables rapid development of completely homozygous maize lines and offers significant opportunities for fast-track development and release of elite cultivars. Besides simplified logistics and reduced costs, use of DH lines in conjunction with molecular markers significantly improves genetic gains and breeding efficiency. DH lines also are valuable tools in marker-trait association studies, molecular marker-assisted or genomic selection-based breeding, and functional genomics. Global, collaborative wheat research brings enormous gains for developing country farmers, particularly in more marginal environments, according to an article in the Centenary Review of the Journal of Agricultural Science.

Global, collaborative wheat research brings enormous gains for developing country farmers, particularly in more marginal environments, according to an article in the Centenary Review of the Journal of Agricultural Science. Keepers of worldwide maize germplasm collections meet at CIMMYT to see how they can work together to protect and conserve these resources.

Keepers of worldwide maize germplasm collections meet at CIMMYT to see how they can work together to protect and conserve these resources.

In the war against drought each victory is very hard-fought. Stress tolerant maize will make a difference.

In the war against drought each victory is very hard-fought. Stress tolerant maize will make a difference.