Three major commercial maize seed exporting countries in southern Africa found free from maize lethal necrosis

NAIROBI, Kenya (CIMMYT) – Three major commercial maize-growing and seed exporting countries in southern Africa were found to be so far free from the deadly maize lethal necrosis (MLN) disease. MLN surveillance efforts undertaken by national plant protection organizations (NPPOs) in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe in 2016 have so far revealed no incidence of MLN, including the most important causative agent, maize chlorotic mottle virus (MCMV).

The three countries export an estimated 7,000 metric tons of maize seed to Angola, Botswana, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda, Swaziland and Tanzania for commercial cultivation by millions of smallholder farmers whose households rely on maize as a staple food.

MLN surveys were conducted as part of ongoing efforts through a project on MLN Diagnostics and Management, funded by U.S. Department for International Development (USAID) East Africa Mission, to strengthen the capacity of NPPOs on surveillance and diagnostics. A total of 12 officers were equipped with knowledge on modern sampling and diagnostics techniques to test plants and seed lots for MLN causing viruses; this was done through a training workshop held in Harare, Zimbabwe on March 3 and 4, 2016 facilitated by scientists working with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

The NPPO teams from Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe then undertook surveys of farmers’ and commercial maize seed production fields, including testing (through MCMV immunostrips) for possible presence of the virus.

“When CIMMYT called the first stakeholders awareness meeting we realised we needed to do this surveillance as soon as possible to ascertain MLN status in the country – and so the training was very important and extremely useful,” said Maimouna Abass, a plant health inspector at Zambia Agriculture Research Institute (ZARI). “The fact that we went to the field and successfully conducted the surveys using the MLN diagnostics and sampling techniques learnt was great.”

Abass and three colleagues who participated in the training, trained 10 other inspectors who took part in the surveillance work.

The results from farmers’ fields, commercial seed production fields and agri-seed dealers, showed negative results for the presence of MCMV and MLN. The MLN surveillance techniques and protocols used across all the three countries were similar, making it possible to effectively compare the results.

“The harmonization of the protocols, across the teams from Malawi and Zambia, was important for me, since this meant that the three countries were able to do the same surveillance using the same protocols and applying the same design across all the countries,” said Nhamo Mudada, chief research officer from the Plant Quarantine Station in Zimbabwe.

Although the MLN disease has not been detected in the southern Africa region, the risk of incidence still remains high through various means, including insect vectors, contaminated seed, and cross-border grain transfers. Therefore, continued caution and stringent surveillance, monitoring and diagnostic measures are required to prevent the possible incidence and spread of MLN into the non-endemic countries.

Further surveillance work will be conducted in 2017, so that each team can cover other targeted areas within their respective countries. MLN surveillance using harmonized protocols will also be undertaken in the MLN-endemic countries, namely Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda. Through systematic surveillance efforts, NPPOs, seed companies and policymakers can clearly understand the prevalence of MLN in specific areas in an endemic country for targeted management. Also, seed companies will be able to target production of commercial seed in MLN-free areas.

As this work progresses, B. M. Prasanna, director of the CGIAR Research Program on MAIZE and CIMMYT’s Global Maize Program as well as Leader for the MLN Diagnostics and Management Project, emphasized the need to intensively deploy MLN-tolerant and resistant varieties, not only in the MLN-endemic countries in eastern Africa, but also in the non-endemic countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

“We have about 22 new, high-yielding, MLN-tolerant or resistant hybridsthat are presently under national performance trials in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. We actively encourage seed companies operating in southern Africa to take up promising pre-commercial hybrids with MLN tolerance or resistance from CIMMYT, for release, scale up and deployment to the farmers,” Prasanna said. “Diagnostics and surveillance have to go hand in hand with deployment of new improved varieties that can effectively respond to the MLN challenge.”

In the East African countries of Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda, seed companies have already released MLN-tolerant varieties. While one hybrid is already being commercialized in Uganda, three more are expected to reach farmers in Kenya and Tanzania from 2017.

“There is also now a very urgent need to deploy MLN resistant varieties in Rwanda and Ethiopia. We need to convey this message to the government and seed companies and work closely to get the seed of MLN resistant varieties to the farmers as soon as possible,” Prasanna added.

The MLN diagnostics and management project, which is funded by the U.S. Department for International Development (USAID), supports work aimed at preventing the spread of MCMV from MLN-endemic to non-endemic areas in sub-Saharan Africa. USAID also supports the commercial seed sector and phytosanitary systems in targeted countries (Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe), in the production of MCMV-free commercial seed, and promotes the use of clean hybrid seed by the farmers.

A new strategic direction

A new strategic direction

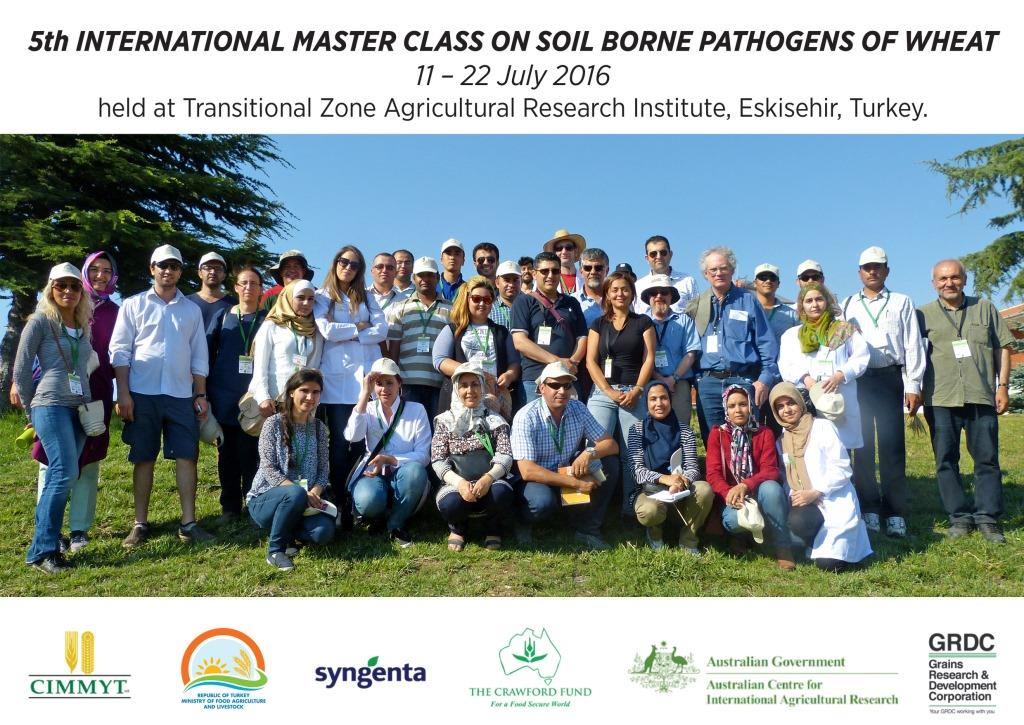

ESKISEHIR, Turkey — The 5th International Master Class on Soil Borne Pathogens of Wheat held at the Transitional Zone Agricultural Research Institute (TZARI), Eskisehir, Turkey, on 11-23 July 2016, brought together 45 participants from 16 countries of Central and West Asia and North Africa.

ESKISEHIR, Turkey — The 5th International Master Class on Soil Borne Pathogens of Wheat held at the Transitional Zone Agricultural Research Institute (TZARI), Eskisehir, Turkey, on 11-23 July 2016, brought together 45 participants from 16 countries of Central and West Asia and North Africa.