John R. Porter, noted crop and climate scientist, becomes chairperson of the Independent Steering Committee for global wheat research

EL BATAN, Mexico (8 November 2017) – Professor Dr. John R. Porter, from the Agropolis/Montpellier Sup agro/INRA/CIRAD conglomeration in Montpellier, France, has been elected as Chair of the Independent Steering Committee that advises the CGIAR Research Program on Wheat (known as WHEAT) on research strategy, priorities and program management. In this appointment, Porter succeeds Dr Tony Fischer, Honorary Research Fellow, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Australia.

agro/INRA/CIRAD conglomeration in Montpellier, France, has been elected as Chair of the Independent Steering Committee that advises the CGIAR Research Program on Wheat (known as WHEAT) on research strategy, priorities and program management. In this appointment, Porter succeeds Dr Tony Fischer, Honorary Research Fellow, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Australia.

An internationally recognized researcher and teacher in crop ecology and physiology, biological modelling, and agricultural ecology, Porter’s contributions have focused on climate change, agronomy, and ecosystem services.

“I am very proud and pleased to be elected as chair of the WHEAT Steering Committee. This CGIAR research program connects over 300 partners into a global alliance for climate-resilient and profitable wheat agri-food systems,” Porter said.

“Accounting for a fifth of the world’s food, wheat is the main source of protein in the developing world and is second only to rice as a source of calories for consumers there,” Porter explained. “The challenge for WHEAT is no less than to raise the crop’s productivity and keep wheat affordable for today’s 2.5 billion resource-poor consumers in 89 countries and for a world population that will surpass 9 billion around mid-century.”

Porter observed that this must be done while cutting greenhouse gas emissions and improving soil health, in wheat-based cropping systems. “As WHEAT moves into its 2nd Phase,” he said, “I would like the Independent Steering Committee to continue the work pioneered by my predecessor Tony Fischer and look at some new areas, such as human capacity development and innovation in wheat-based food production systems.”

Meeting wheat demand, protecting food and farming from worsening climate impacts

According to Porter, WHEAT is actively catalyzing the efforts of CGIAR and partner institution scientists, farmers, governments and private companies in lower and middle-income countries, to develop and share climate-smart innovations that increase farm resilience and productivity, while reducing the climate footprint.

Technology such as high-yielding wheat varieties that tolerate drought and high temperatures, as well as resisting new or modified strains of deadly crop diseases spawned in rapidly warming environments, are the outputs from WHEAT research that lead to positive outcomes for farmers and consumers.

Developing such technologies requires that WHEAT also invest in human capacity development. “Varieties derived from WHEAT breeding lines are already sown on nearly half of the world’s wheat lands and which bring economic benefits of about $3.1 billion each year,” Porter said, citing a 2016 analysis of WHEAT impacts.

Resource-conserving cropping practices from WHEAT, such as more targeted use of nitrogen fertilizers or sowing wheat into untilled soils and crop residues, can raise wheat farmers’ incomes while curbing greenhouse gas emissions, if widely adopted, he added. “Zero tillage is already being used to sow wheat on 1.8 million hectares in South Asia’s extensive rice-wheat rotations, and state government officials in India are implementing policies to support more widespread adoption.”

Perfect experience for the job

A member of the WHEAT Independent Steering Committee since 2014, Porter has published more than 140 papers in reviewed journals, won four international prizes for research and teaching, and served as president of the European Society for Agronomy and was Chief Editor of the European Journal of Agronomy for many years. He led the writing of the chapter on food production and security for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 5th Assessment. Porter was elected as both a Fellow of the Royal Swedish Academy for Agriculture and Forestry and the European Academy of Sciences in 2014 and was knighted by the French government via the Order of Agriculture Merit in March 2016. Porter is an emeritus professor at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark and the Natural Resources Institute at the University of Greenwich UK and an honorary professor at Lincoln University, New Zealand. He is a member of the Scientific Council of the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA) and currently consulting professor at Montpellier SupAgro, France on a project for Capacity Building in Crop Modelling financed by the Agropolis Foundation and Labex Agro.

For more information or interviews:

Mike Listman | Communications officer

CGIAR Research Program on Wheat (http://wheat.org)

tel: +52 (55) 5804 7537

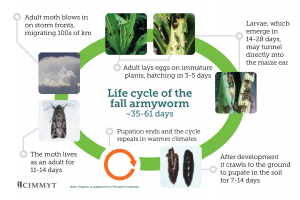

DES MOINES, Iowa (CIMMYT) – Without proper control methods, the Fall Armyworm (FAW) menace could lead to maize yield losses estimated at $2.5 to $6.2 billion a year in just 12 of the 28 African countries where the pest has been confirmed, scientists from the Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International, (CABI)

DES MOINES, Iowa (CIMMYT) – Without proper control methods, the Fall Armyworm (FAW) menace could lead to maize yield losses estimated at $2.5 to $6.2 billion a year in just 12 of the 28 African countries where the pest has been confirmed, scientists from the Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International, (CABI)  Prasanna will be participating in the 2017 Borlaug Dialogue in Des Moines, Iowa, and will part of a panel discussion, on October 19, titled “

Prasanna will be participating in the 2017 Borlaug Dialogue in Des Moines, Iowa, and will part of a panel discussion, on October 19, titled “