Moving out of poverty or staying poor

Although the conventional wisdom in South Asian rural villages is that men are principally responsible for pulling their families out of poverty, our recent study showed the truth to be more subtle, and more female.

In our new paper we dig into focus groups and individual life stories in a sample of 32 farming villages from five countries of South Asia. Although we asked about both men’s and women’s roles, focus groups of both sexes emphasized men in their responses — whether explaining how families escaped poverty or why they remained poor.

“Women usually cannot bring a big change, but they can assist their men in climbing up,” explains a member of the poor men’s focus group from Ismashal village (a pseudonym) of Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

The focus group testimonies presented rich examples of the strong influence of gender norms: the social rules that dictate differential roles and conducts for men and women in their society. These norms significantly influenced how local people conceived of movements in and out of poverty in their village and in their own lives.

According to the women’s focus group from Rangpur district in Bangladesh, women “cannot work outside the home for fear of losing their reputation and respect.”

However, in these same communities, men’s and women’s productive roles proved far more variable in the mobility processes of their families than conveyed by the focus groups. We encountered many households with men making irregular or very limited contributions to family maintenance. This happens for a number of reasons, including men’s labor migration, disability, family conflict and separations, aging and death.

What’s more, when sharing their life stories in individual interviews, nearly every woman testified to her own persistent efforts to make a living, cover household expenses, deal with debts, and, when conditions allowed, provide a better life for their families. In fact, our life story sample captured 12 women who testified to making substantial contributions to moving their families out of poverty.

Movers and shakers

We were especially struck by how many of these women “movers” were employing innovative agricultural technologies and practices to expand their production and earnings.

“In 2015, using zero tillage machines I started maize farming, for which I had a great yield and large profit,” reports a 30-year-old woman and mother of two from Matipur, Bangladesh who brought her family out of poverty.

Another 30-year-old mover, a farmer and mother of two from the village of Thool in Nepal, attests to diversification and adoption of improved cultivation practices: “I got training on vegetable farming. In the beginning the agriculture office provided some vegetable seeds as well. And I began to grow vegetables along with cereal crops like wheat, paddy, maize, oats. […] I learnt how to make soil rows.”

Among the women who got ahead, a large majority credited an important man in their life with flouting local customs and directly supporting them to innovate in their agricultural livelihoods and bring their families out of poverty.

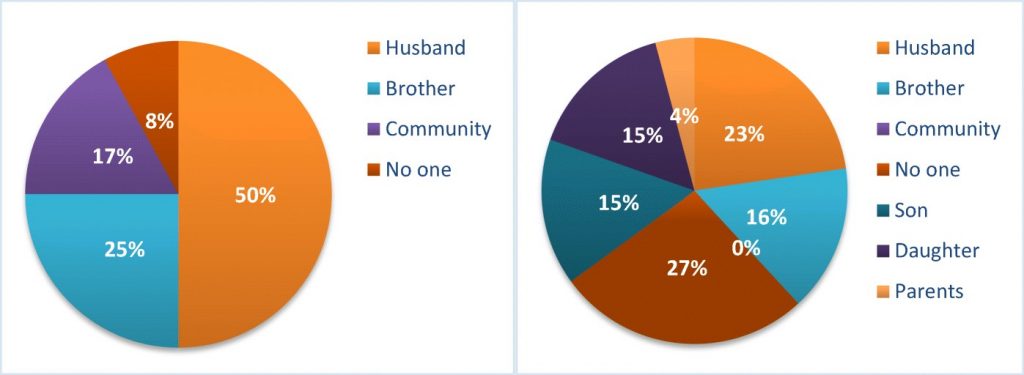

Across the “mover” stories, women gained access to family resources which enabled them to step up their livelihood activities. For example, three quarters of the women “movers” spoke of husbands or brothers supporting them to pursue important goals in their lives.

Sufia, from a village in the Rajshahi district of Bangladesh, describes how she overcame great resistance from her husband to access a farm plot provided by her brother. The plot enabled Sufia to cultivate betel leaves and paddy rice, and with those profits and additional earnings from livestock activities, she purchased more land and diversified into eggplant, chilies and bitter gourd. Sufia’s husband had struggled to maintain the family and shortly after Sufia began to prosper, he suffered a stroke and required years of medical treatments before passing away.

When Sufia reflects on her life, she considers the most important relationship in her life to be with her brother. “Because of him I can now stand on my two feet.”

We also studied women and their families who did not move out of poverty. These “chronic poor” women rarely mentioned accessing innovations or garnering significant benefits from their livelihoods. In these life stories, we find far fewer testimonies about men who financially supported a wife or sister to help her pursue an important goal.

The restrictive normative climate in much of South Asia means that women’s capacity to enable change in their livelihoods is rarely recognized or encouraged by the wider community as a way for a poor family to prosper. Still, the life stories of these “movers” open a window onto the possibilities unlocked when women have opportunities to take on more equitable household roles and are able to access agricultural innovations.

The women movers, and the men who support them, provide insights into pathways of more equitable agricultural change. What we can learn from these experiences holds great potential for programs aiming to relax gender norms, catalyze agricultural innovation, and unlock faster transitions to gender equality and poverty reduction in the region. Nevertheless, challenging social norms can be risky and can result in backlash from family or other community members. To address this, collaborative research models offer promise. These approaches engage researchers and local women and men in action learning to build understanding of and support for inclusive agricultural change. Our research suggests that such interventions, which combine social, institutional and technical dimensions of agricultural innovation, can help diverse types of families to leave poverty behind.

Read the full study:

Gender Norms and Poverty Dynamics in 32 Villages of South Asia