Representatives from ministries of agriculture and national agricultural research systems (NARS) in Ethiopia and Kenya recently joined funder representatives and technical experts from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) to renew a long-standing collaboration under the auspices of an ambitious new project, Accelerating Genetic Gains in Maize and Wheat for Improved Livelihoods (AGG).

AGG is a 5-year project that brings together partners in the global science community and in national agricultural research and extension systems to accelerate the development of higher-yielding varieties of maize and wheat — two of the world’s most important staple crops. Funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the UK Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO), the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research (FFAR), AGG fuses innovative methods that improve breeding efficiency and precision to produce varieties that are climate-resilient, pest- and disease-resistant, highly nutritious, and targeted to farmers’ specific needs.

Ethiopia and Kenya: CIMMYT’s longstanding partners

The inception meeting for the wheat component of AGG in East Africa drew more than 70 stakeholders from Ethiopia and Kenya: the region’s primary target countries for wheat breeding. These two countries have long-standing relationships with CIMMYT that continue to deliver important impacts. Ninety percent of all wheat in Ethiopia is derived from CIMMYT varieties, and CIMMYT is a key supporter of the Ethiopian government’s goal for wheat self-sufficiency. Kenya has worked with CIMMYT for more than 40 years, and hosts the world’s biggest screening facilities for wheat rust diseases, with up to 40,000 accessions tested each year.

AGG builds on these successes and on the foundations built by previous projects, notably Delivering Genetic Gain in Wheat, led by Cornell University. The wheat component of AGG works in parallel with a USAID-funded “zinc mainstreaming” project, meeting the demand for increased nutritional quality as well as yield and resilience.

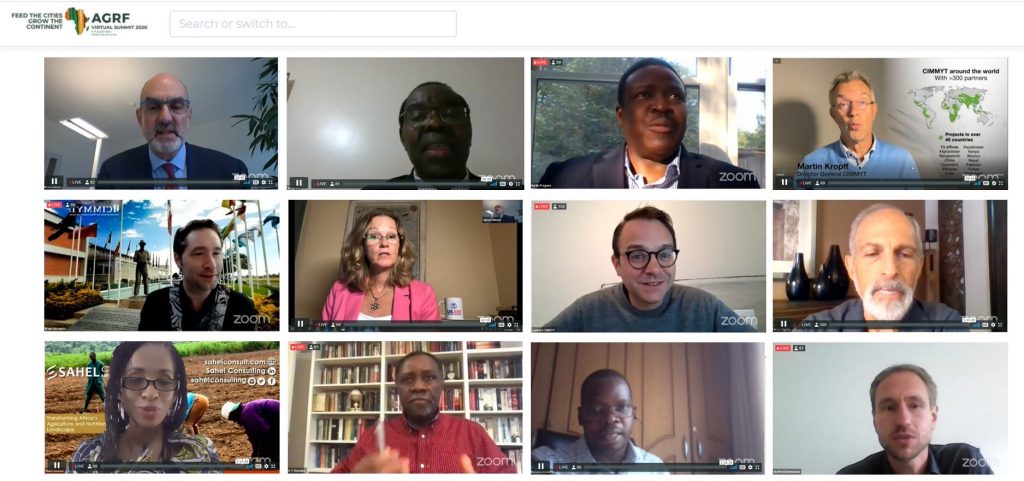

CIMMYT Director General Martin Kropff gave key remarks at the stakeholder gathering, which took place Thursday, August 20.

“Cooperation between CIMMYT and Ethiopia and Kenya – as in all the countries where CIMMYT works – has had tremendous impact,” he said. “We are proud, not for ourselves, but for the people we work for: the hundreds of millions of poor people and smallholders who rely on wheat and maize for their daily food and incomes.”

“AGG will raise this spirit of global cooperation to a new level.”

AGG Project Leader and CIMMYT Interim Deputy Director General for Research Kevin Pixley introduced the new project as a “unique and important” project that challenges every stakeholder to grow.

“What we would like to achieve is a step change for all of us, he told the stakeholders. “Each of us has the opportunity and the challenge to make a difference and that’s what we’re striving to do.”

Representatives from the agricultural research communities of both target countries emphasized the significance of their long collaboration with CIMMYT and their support for the project.

The Honorable Mandefro Nigussie, Ethiopia’s State Minister of Agriculture, confirmed the ongoing achievements of CIMMYT collaboration in his country.

“Our partnership with CIMMYT […] has yielded several improved varieties that increased productivity twofold over the last 20 years. He referred to Ethiopia’s campaign to achieve self-sufficiency in wheat. “AGG will make an immense contribution to this. The immediate and intermediate results can help achieve the country’s ambitious targets.”

A holistic and gender-informed approach

Deputy Director of Crops at the Kenya Agriculture and Livestock Organization (KALRO) Felister Makini, representing the KALRO Director General Eliud Kireger, noted the project’s strong emphasis on gender-intentional variety development and gender-informed analysis to ensure female farmers have access to varieties that meet their needs and the information to successfully adopt them.

“The goal of this new project will indeed address KALRO’s objective of enhancing food security and nutrition in Kenya,” she said. “This is because AGG not only brings together wheat breeding and optimization tools and technologies, but also considers gender and socioeconomic insights, which will be pivotal to our envisaged strategy to achieve socioeconomic change.”

Funding partners keen for AGG to address future threats

Before CIMMYT wheat experts took the virtual floor to describe specific workplans and opportunities for partner involvement, a number of funder representatives shared candid and inspiring thoughts.

“We are interested in delivery,” said Alan Tollervey of FCDO, formerly the UK Department for International Development. “That is why we support AGG, because it is about streamlining and modernizing the delivery of products […] directly relevant to both the immediate demands of poor farmers in developing countries and the global demand for food – but also addressing the future threats that we see coming.”

Hailu Wordofa, Agricultural Technology Specialist at the Bureau for Resilience and Food Security at USAID highlighted the importance of global partnerships for past success and reiterated the ambitious targets of the current project.

“We expect to see genetic gains increase and varieties […] replaced by farmer-preferred varieties,” he reminded stakeholders. “To make this happen, we expect CIMMYT’s global breeding program to use optimal breeding approaches and develop strong and truly collaborative relationships with NARS partners throughout the entire process.”

“Wheat continues to be a critical staple crop for global food security and supporting CIMMYT’s wheat breeding program remains a high priority for USAID,” he assured the attendees.

He also expressed hope that AGG would collaborate other projects working in parallel, including the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Applied Wheat Genomics at Kansas State University, and the International Wheat Yield Partnership.

FFAR Scientific Program Director Jeff Rosichan called AGG a “really ambitious project that takes a comprehensive look at the research gaps and challenges and how to translate that research into farmers’ fields.”

Agriculture prevails even under COVID-19

The global COVID-19 pandemic was not ignored as one of several challenges during this time of change and transition.

“As we speak today, despite the challenge that we have with the COVID-19, I am proud to say that work on the nurseries is on-going. We are able to apply [our] skills and deliver world-class science,” said Godwin Macharia, center director at KALRO-Njoro.

“This COVID-19 pandemic has shown us that there is a great need globally to focus on food equity. I think this project allows that to happen,” said Jeff Rosichan from FFAR.

Transformations are also happening at the research organization and funding level. CIMMYT Director General Martin Kropff noted that “demand-driven solutions” for “affordable, efficient and healthy diets produced within planetary boundaries” are an important part of the strategy for One CGIAR, the ongoing transformation of CGIAR, the world’s largest public research network on food systems, of which CIMMYT is a member.

Hans Braun, director of CIMMYT’s Global Wheat Program reminded attendees that, despite these changes, one important fact remains. “The demand for wheat will continue to grow for many years to come, and we must meet it.”

Cover photo: Harvesting golden spikes of wheat in Ethiopia. (Photo: Peter Lowe/CIMMYT)