AgriLAC Resiliente presented in Guatemala

Latin America and the Caribbean possess the largest reserve of arable land on the planet, 30% of renewable water, 46% of tropical forests and 30% of biodiversity. These resources represent an important contribution to the world’s food supply and other ecosystem services. However, climate change and natural disasters, exacerbated by COVID-19, have deteriorated economic and food security, destabilizing communities and causing unprecedented migration, impacting not only the region but the entire world.

Against this regional backdrop, AgriLAC Resiliente was created. This CGIAR Initiative seeks to increase the resilience, sustainability and competitiveness of the region’s agrifood systems and actors. It aims to equip them to meet urgent food security needs, mitigate climate hazards, stabilize communities vulnerable to conflict and reduce forced migration.

Guatemala was selected to present this Initiative, which will also impact farmers in Colombia, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua and Peru, and will be supported by national governments, the private sector, civil society, and regional and global donors and partners.

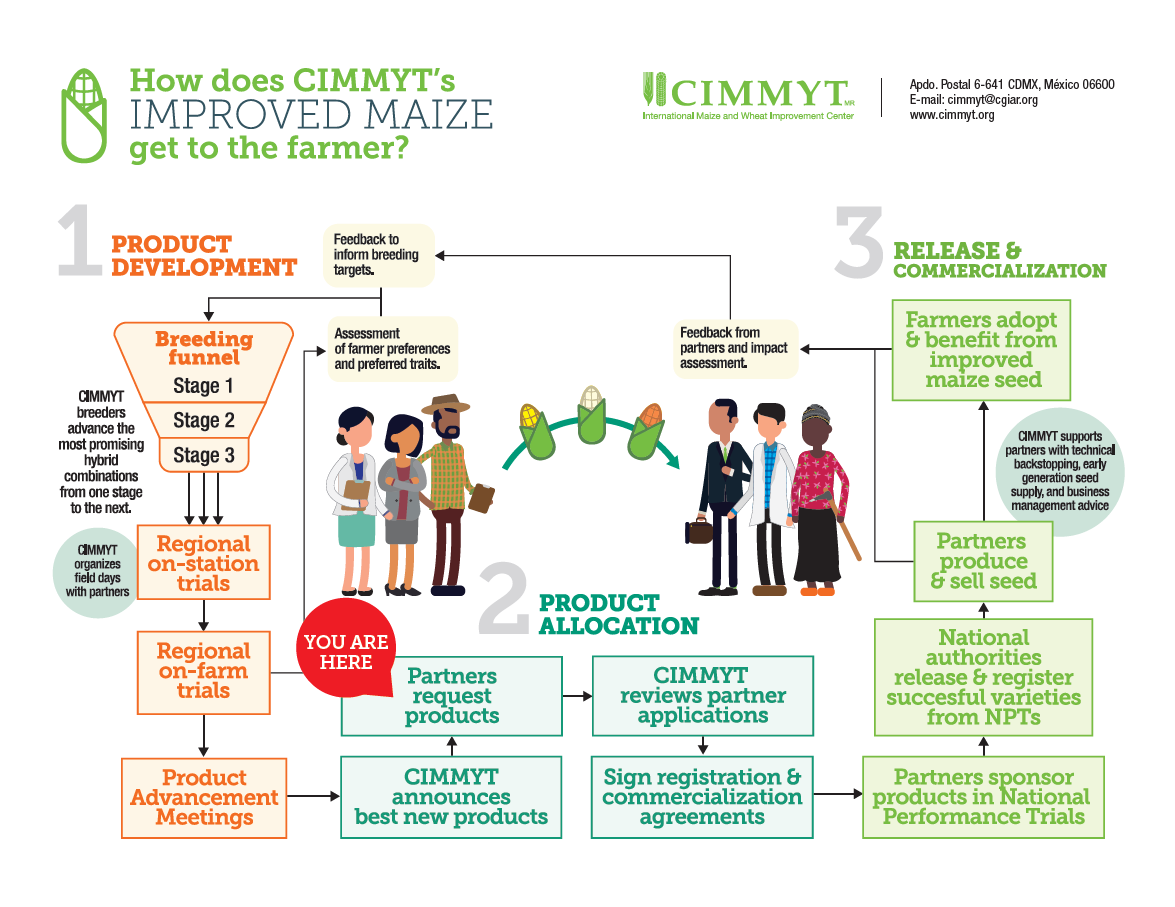

At a workshop on June 27–28, 2022, in Guatemala City, partners consolidated their collaboration by presenting the Initiative and developing a regional roadmap. Workshop participants included representatives from the government of Guatemala, NGOs, international cooperation programs, the private sector, producer associations, and other key stakeholders from the host country. Also at the workshop were the leaders from CGIAR research Centers involved in the Initiative, such as the Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), the International Potato Center (CIP) and the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Impact through partnerships

“Partnerships are the basis for a future of food security for all through the transformation of food systems in the context of a climate crisis. AgriLAC’s goal of a coordinated strategy and regional presence will facilitate strong joint action with partners, donors, and producers, and ensure that CGIAR science continues to be leveraged so that it has the greatest possible impact,” said Joaquín Lozano, CGIAR Regional Director for Latin America and the Caribbean.

This Initiative is one of many CGIAR Initiatives in Latin America and consists of five research components: Climate and nutrition that seeks to use collaborative innovations for climate resilient and nutritious agrifood systems; Digital agriculture through the use of digital and inclusive tools for the creation of actionable knowledge; Low-emission competitiveness focused on agroecosystems, landscapes and value chains that are low in sustainable emissions; Innovation and scaling with the Innova-Hubs network for agrifood innovations and scaling; and finally, Science for timely decision making and establishment of policies, institutions, and investments for resilient, competitive and low-emission agrifood systems.

“We know the important role that smallholder farmers, both women and men, will play in the appropriation of the support tools that the Initiative will offer, which will allow them to make better decisions for the benefit of their communities. That is why one of the greatest impacts we expect from the project will be the contribution to gender equality, the creation of opportunities for youth, and the promotion of social inclusion,” said Carolina González, leader of the Initiative, from the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT.

Bram Govaerts, Director General of CIMMYT, said: “In Guatemala, we have had the opportunity to work side by side with farmers who today, more than ever, face the vicious circle of conflict, poverty and climate change. Through this Initiative, we hope to continue making progress in the transformation of agrifood systems in Central America, helping to make agriculture a dignified and satisfying job and a source of prosperity for the region’s producers.”

“I realize the importance of implementing strategic actions designed to improve the livelihoods of farmers. The environmental impact of development without sustainable planning puts at risk the wellbeing of humanity. The Initiatives of this workshop contribute to reducing the vulnerability of both productive systems and farmers and their families. This is an ideal scenario to strengthen alliances that allow for greater impact and respond to the needs of the country and the region,” said Jose Angel Lopez, Guatemala’s Minister of Agriculture, Livestock and Food.

National and regional strategies

AgriLAC Resiliente will also be presented in Honduras, where national partners will learn more about the Initiative and its role in achieving a resilient, sustainable, and competitive Latin America and the Caribbean, that will enable it to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

Under the general coordination of CGIAR, other Initiatives are also underway in Guatemala that will synergize with the global research themes toward the transformation of more resilient agrifood systems.

“We are committed to providing a structure that responds to national and regional priorities, needs, and demands. The support of partners, donors and producers will be key to building sustainable and more efficient agrifood systems,” Lozano said.

About CGIAR

CGIAR is a global research partnership for a food-secure future, dedicated to transforming food, land, and water systems in a climate crisis. Its research is carried out by 13 CGIAR Centers/Alliances in close collaboration with hundreds of partners, including national and regional research institutes, civil society organizations, academia, development organizations and the private sector. www.cgiar.org

We would like to thank all Funders who support this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund.

About the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT

The Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) delivers research-based solutions that address the global crises of malnutrition, climate change, biodiversity loss, and environmental degradation. The Alliance focuses on the nexus of agriculture, nutrition and environment. We work with local, national, and multinational partners across Africa, Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean, and with the public and private sectors and civil society. With novel partnerships, the Alliance generates evidence and mainstreams innovations to transform food systems and landscapes so that they sustain the planet, drive prosperity, and nourish people in a climate crisis.

The Alliance is a CGIAR Research Center. https://alliancebioversityciat.org

About CIMMYT

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is an international nonprofit agricultural research and training organization that empowers farmers through science and innovation to nourish the world in the midst of a climate crisis. Applying high-quality science and strong partnerships, CIMMYT works toward a world with healthier, more prosperous people, freedom from global food crises, and more resilient agrifood systems. CIMMYT’s research brings higher productivity and better profits to farmers, mitigates the effects of the climate crisis, and reduces the environmental impact of agriculture.

CIMMYT is a CGIAR Research Center. https://staging.cimmyt.org

About CIP

The International Potato Center (CIP) was founded in 1971 as a research-for-development organization with a focus on potato, sweetpotato and andean roots and tubers. It delivers innovative science-based solutions to enhance access to affordable nutritious food, foster inclusive sustainable business and employment growth, and drive the climate resilience of root and tuber agrifood systems. Headquartered in Lima, Peru, CIP has a research presence in more than 20 countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

CIP is a CGIAR Research Center. https://cipotato.org/

About IFPRI

The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) provides research-based policy solutions to sustainably reduce poverty and end hunger and malnutrition in developing countries. IFPRI currently has more than 600 employees working in over 50 countries. Global, regional, and national food systems face major challenges and require fundamental transformations. IFPRI is focused on responding to these challenges through a multidisciplinary approach to reshape food systems so they work for all people sustainably.

IFPRI is a CGIAR Research Center. www.ifpri.org