Policy brief highlights opportunities to promote balanced nutrient management in South Asia

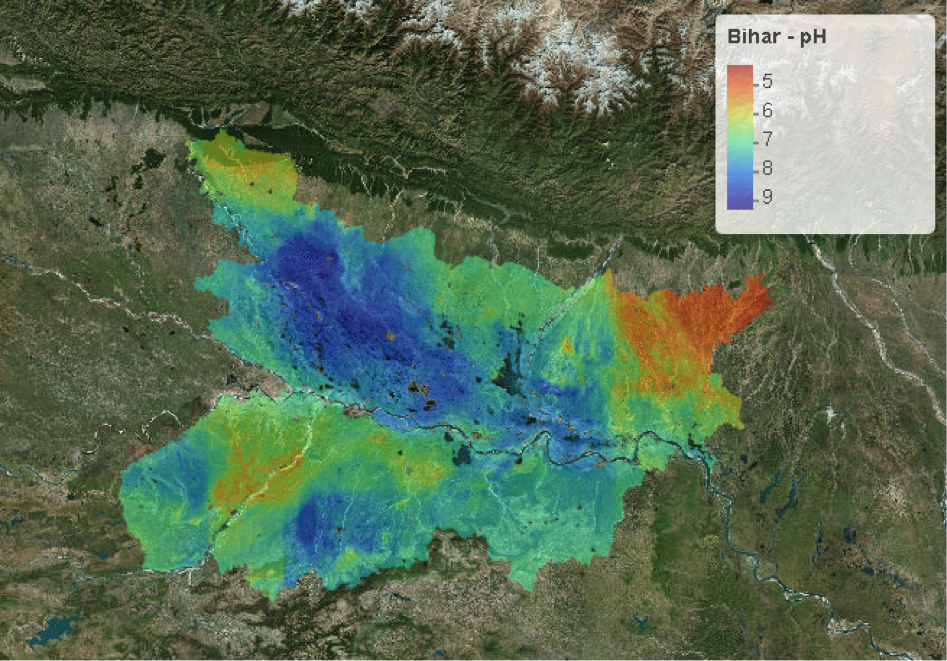

Over the last few decades, deteriorating soil fertility has been linked to decreasing agricultural yields in South Asia, a region marked by inequities in food and nutritional security.

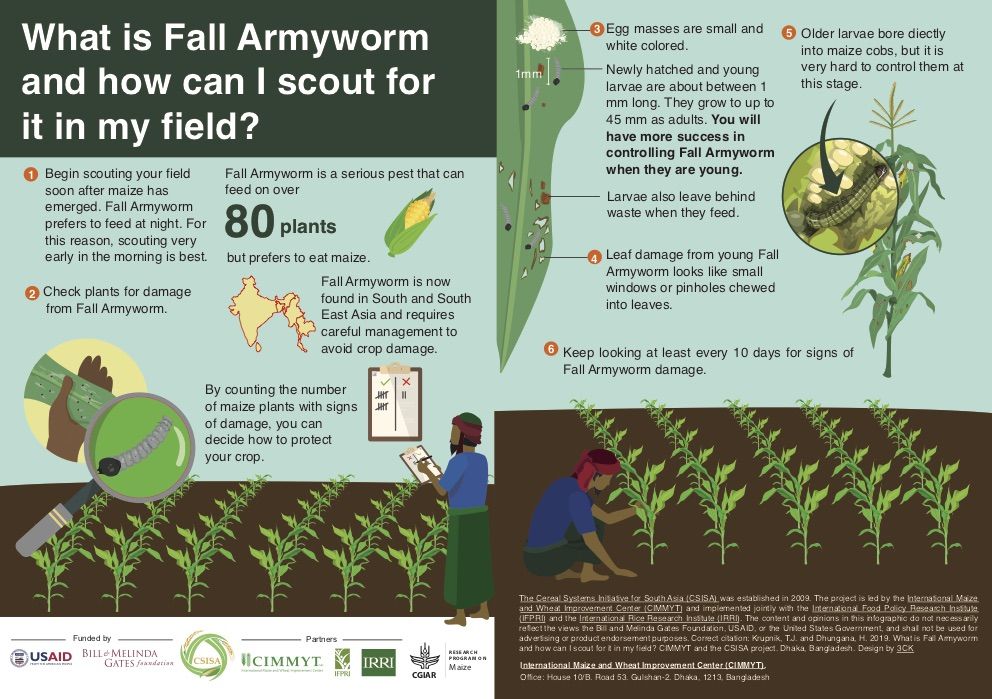

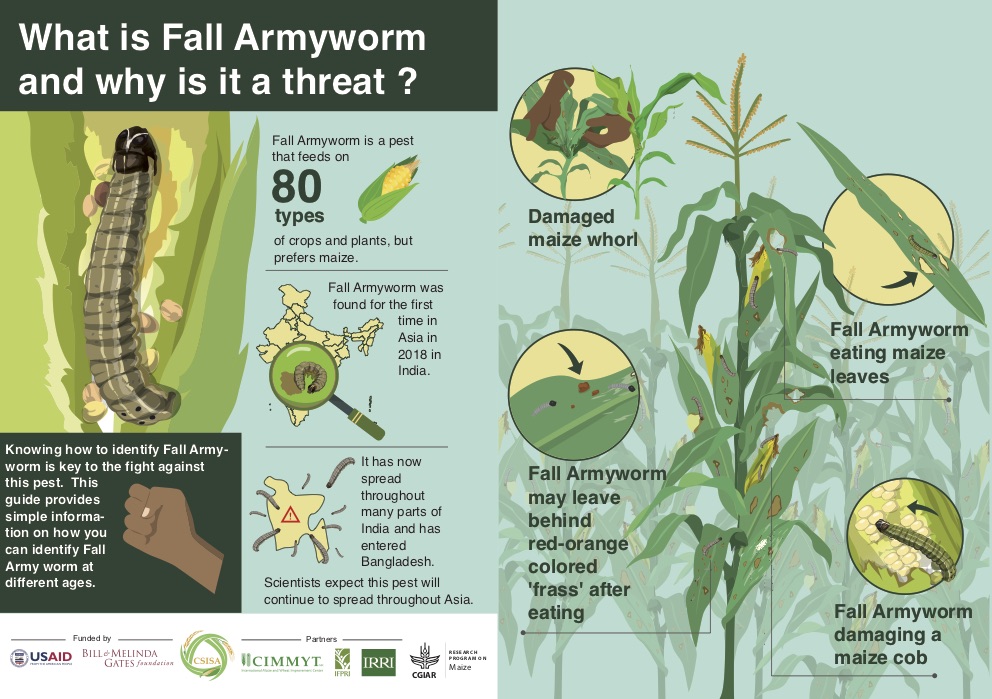

As the demand for fertilizers grows, researchers are working with government and businesses to promote balanced nutrient management and the appropriate use of organic amendments among smallholder farmers. The Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA) has published a new policy brief outlining opportunities for innovation in the region.

Like all living organisms, crops need access to the right amount of nutrients for optimal growth. Plants get nutrients — like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, in addition to other crucially important micronutrients — from soils and carbon, hydrogen, oxygen from the air and water. When existing soil nutrients are not sufficient to sustain good crop yields, additional nutrients must be added through fertilizers or manures, compost or crop residues. When this is not done, farmers effectively mine the soil of fertility, producing short-term gains, but undermining long-term sustainability.

Nutrient management involves using crop nutrients as efficiently as possible to improve productivity while reducing costs for farmers, and also protecting the environment by limiting greenhouse gas emissions and water quality contamination. The key behind nutrient management is appropriately balancing soil nutrient inputs — which can be enhanced when combined with appropriate soil organic matter management — with crop requirements. When the right quantities are applied at the right times, added nutrients help crops yields flourish. On the other hand, applying too little will limit yield and applying too much can harm the environment, while also compromising farmers’ ability to feed themselves or turn profits from the crops they grow.

Smallholder farmers in South Asia commonly practice poor nutrition management with a heavy reliance on nitrogenous fertilizer and a lack of balanced inputs and micronutrients. Declining soil fertility, improperly designed policy and nutrient management guidelines, and weak fertilizer marketing and distribution problems are among the reasons farmers fail to improve fertility on their farms. This is why it is imperative to support efforts to improve soil organic matter management and foster innovation in the fertilizer industry, and find innovative ways to target farmers, provide extension services and communicate messages on cost-effective and more sustainable strategies for matching high yields with appropriate nutrient management.

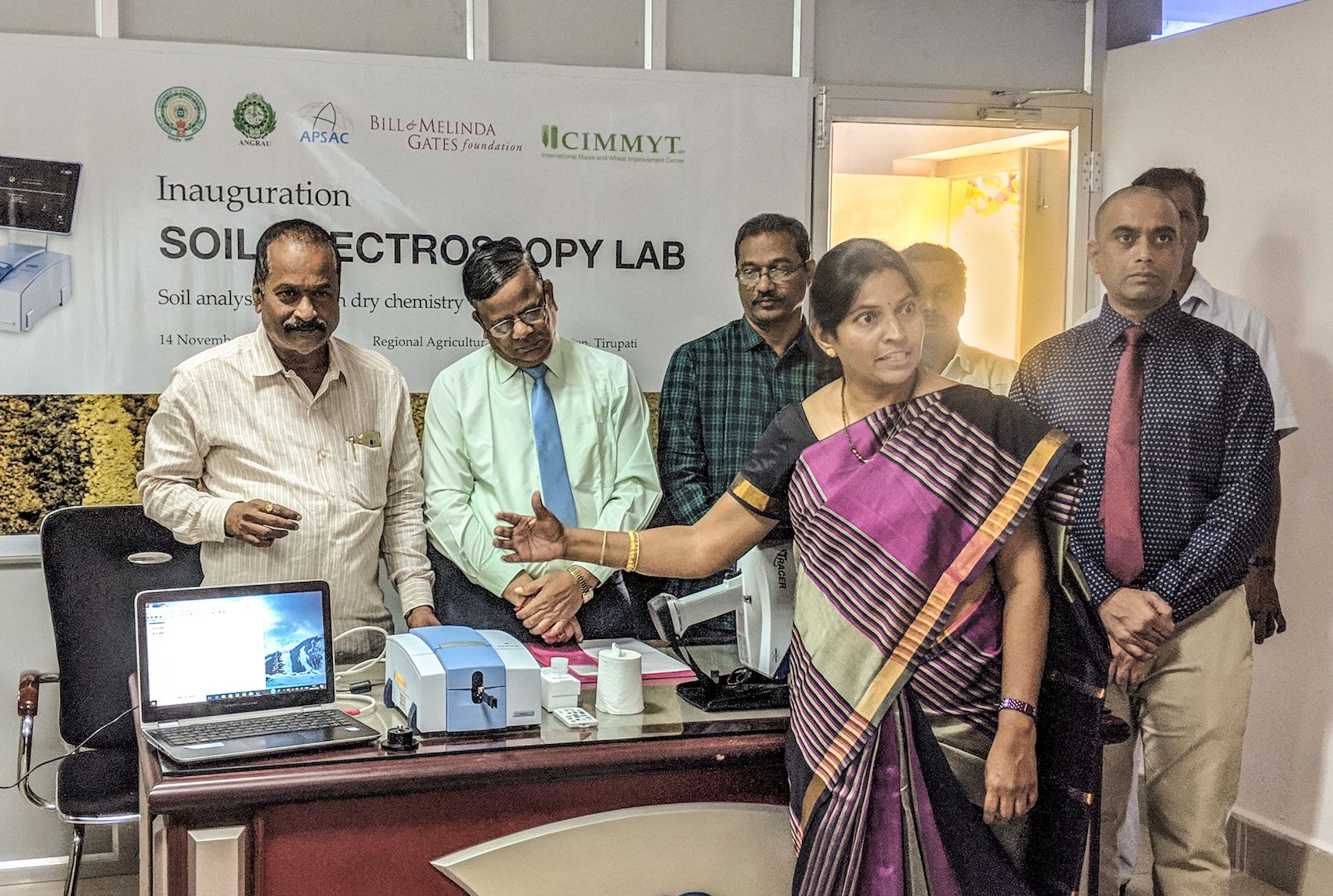

Cross-country learning reveals opportunities for improved nutrient management. The policy brief is based on outcomes from a cross-country dialogue facilitated by CSISA earlier this year in Kathmandu. The meeting saw researchers, government and business stakeholders from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka discuss challenges and opportunities to improving farmer knowledge and access to sufficient nutrients. Several key outcomes for policy makers and representatives of the agricultural development sector were identified during the workshop, and are included in the brief.

Extension services as an effective way to encourage a more balanced use of fertilizers among smallholder farmers. There is a need to build the capacity of extension to educate smallholders on a plant’s nutritional needs and proper fertilization. It also details how farmers’ needs assessments and human-centered design approaches need to be integrated while developing and delivering nutrient application recommendations and extension materials.

Nutrient subsidies must be reviewed to ensure they balance micro and macro-nutrients. Cross-country learning and evidence sharing on policies and subsidies to promote balanced nutrient application are discussed in the brief, as is the need to balance micro and macro-nutrient subsidies, in addition to the organization of subsidy programs in ways that assure farmers get access the right nutrients when and where they are needed the most. The brief also suggests additional research and evidence are needed to identify ways to assure that farmers’ behavior changes in response to subsidy programs.

Market, policy, and product innovations in the fertilizer industry must be encouraged. It describes the need for blended fertilizer products and programs to support them. A blend is made by mixing two or more fertilizer materials. For example, particles of nitrogen, phosphate and small amounts of secondary nutrients and micronutrients mixed together. Experience with blended products are uneven in the region, and markets for blends are nascent in Bangladesh and Nepal in particular. Cross-country technical support on how to develop blending factories and markets could be leveraged to accelerate blended fertilizer markets and to identify ways to ensure equitable access to these potentially beneficial products for smallholder farmers.

Download the CSISA Policy and Research Note:

Development of Balanced Nutrient Management Innovations in South Asia: Lessons from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.

The CSISA project is led by CIMMYT with partners the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) and the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.