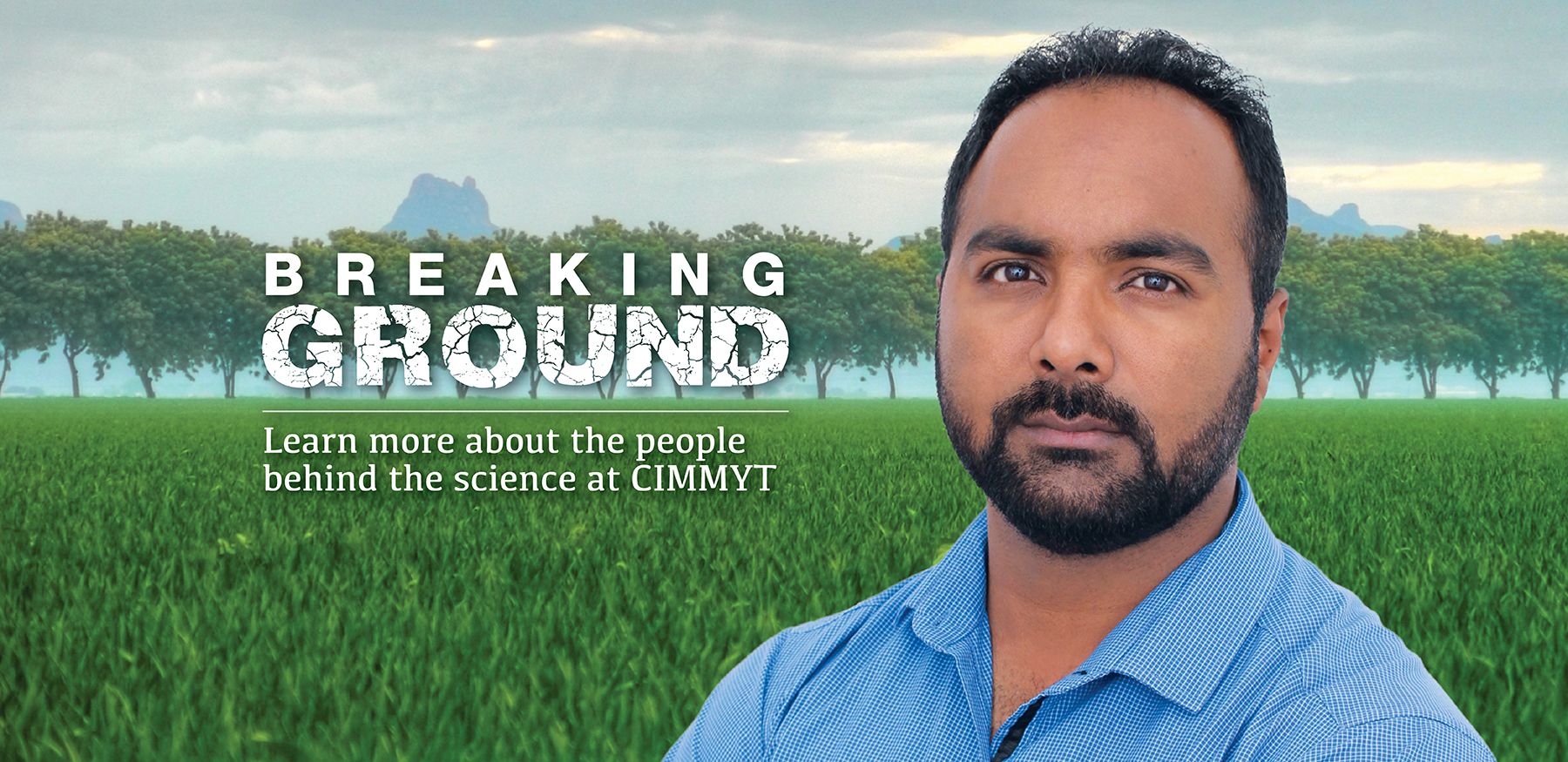

Breaking Ground: Mandeep Randhawa fights wheat diseases using genetic resistance tools

With new pathogens of crop diseases continuously emerging and threatening food production and security, wheat breeder and wheat rust pathologist Mandeep Randhawa and his colleagues at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and the Kenya Agricultural and Research Organization (KALRO) are working tirelessly to identify new sources of rust resistance through gene mapping tools and rigorous field testing.

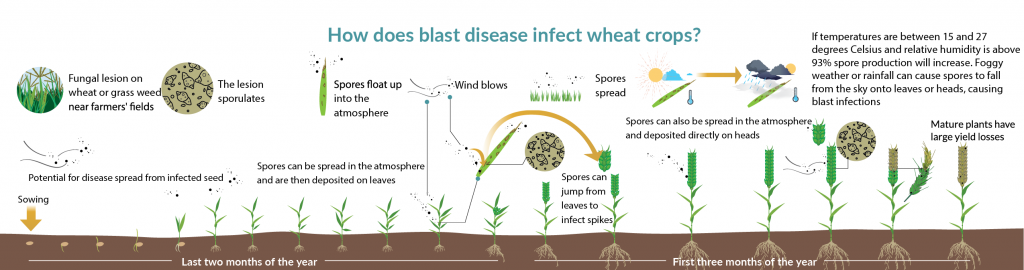

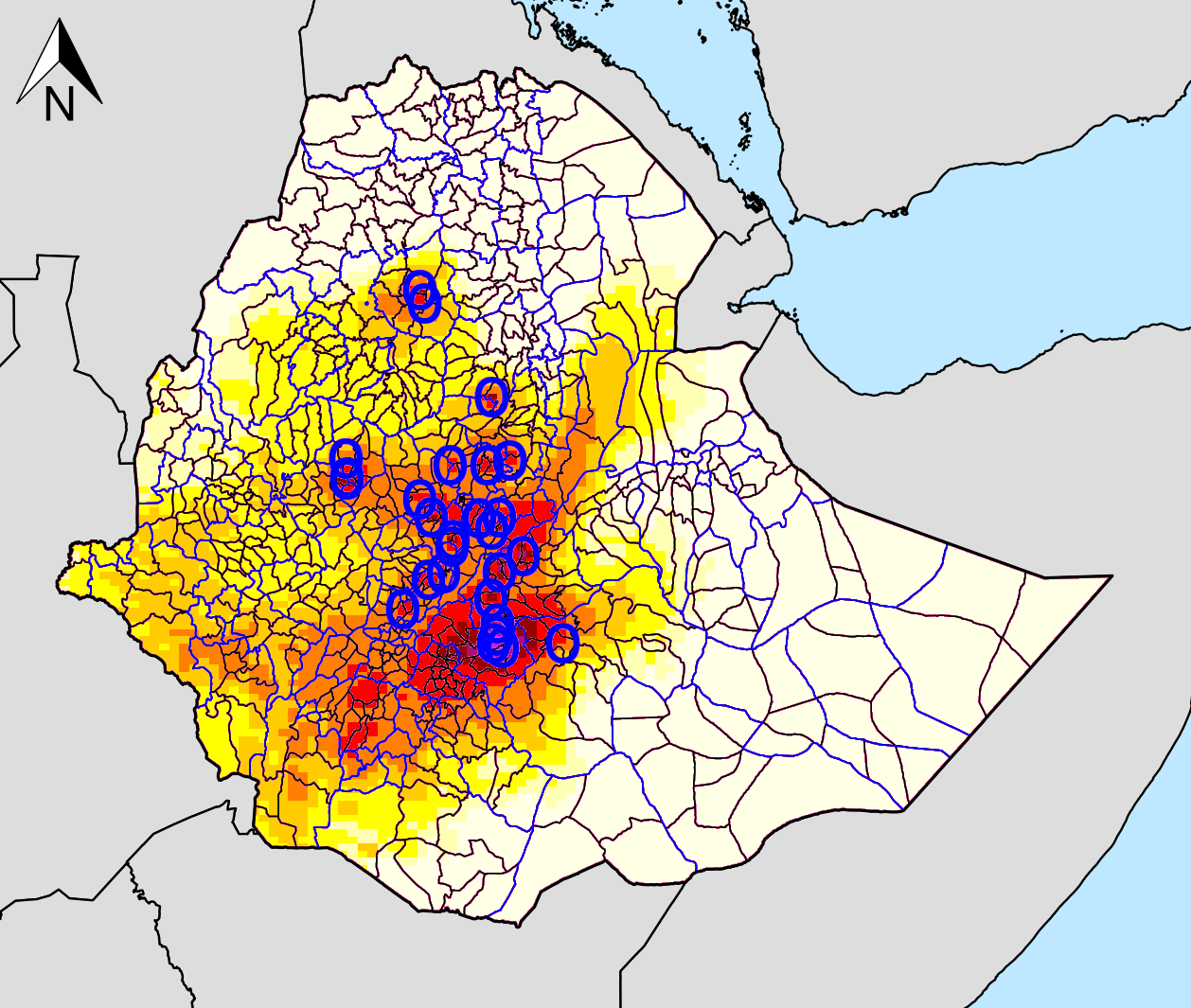

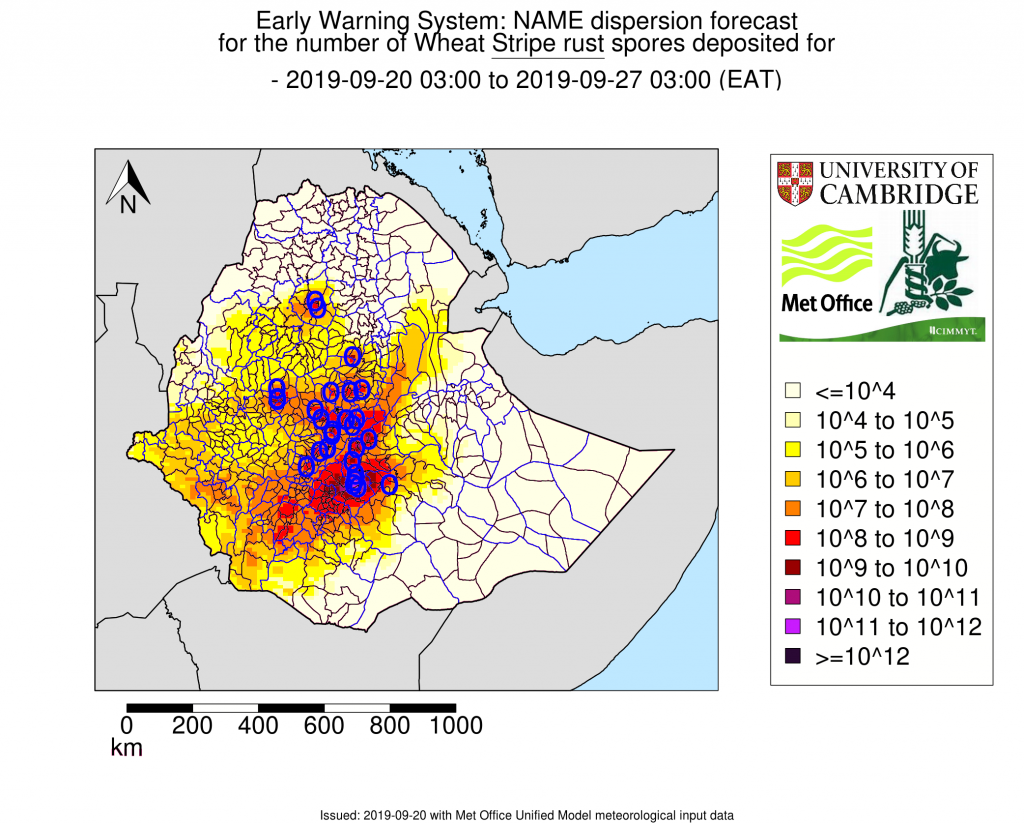

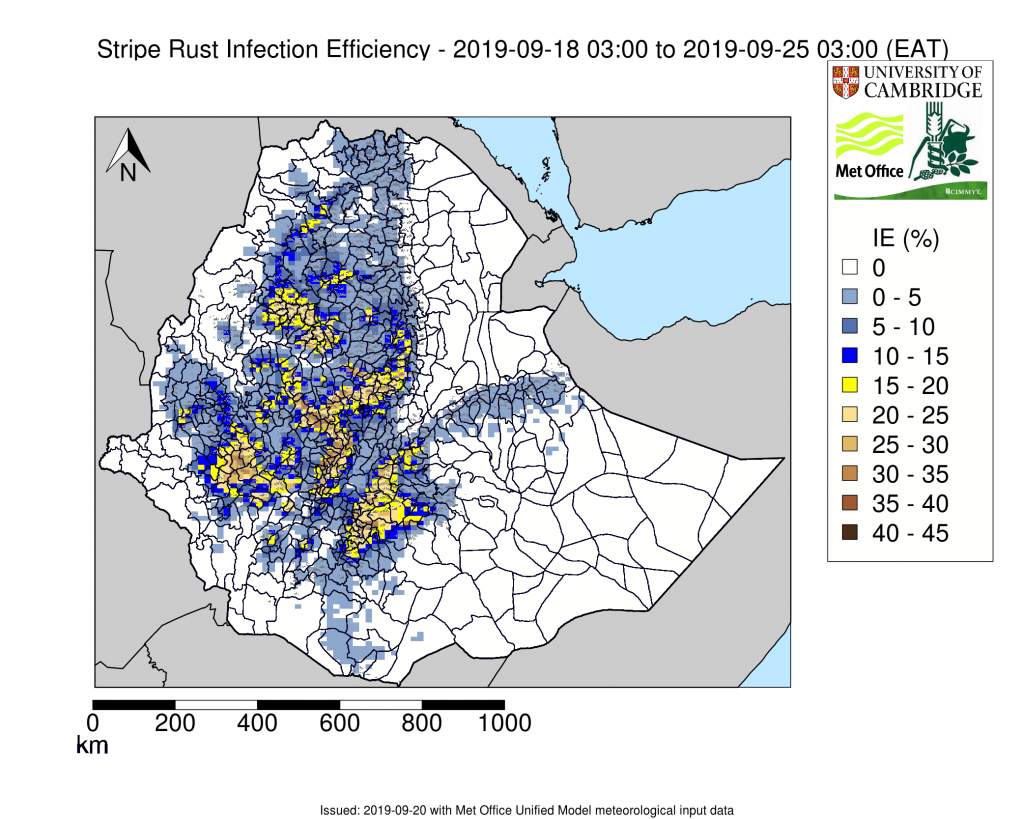

With wheat accounting for around 20% of the world’s calories and protein, outbreaks of disease can pose a major threat to global food security and farmer livelihoods. The most common and prevalent diseases are wheat rusts — fungal diseases that can be dispersed by wind over long distances, which can quickly cause devastating epidemics and dramatically reduce wheat yields.

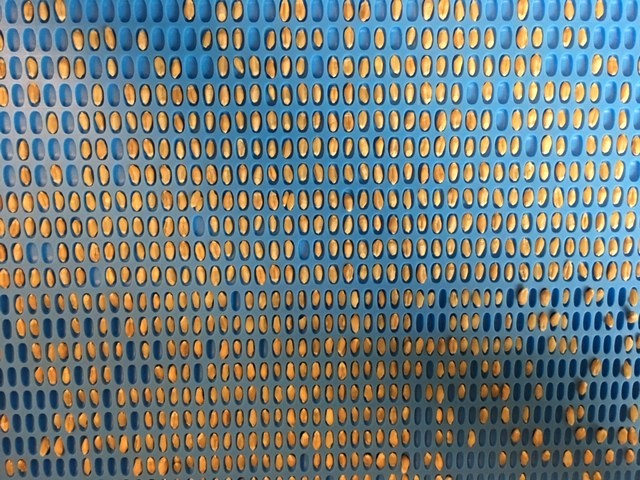

To tackle the problem, Randhawa and his colleagues work on developing improved wheat varieties by combining disease-resistant traits with high yielding ones, to ensure that farmers can get the best wheat yields possible while evading diseases.

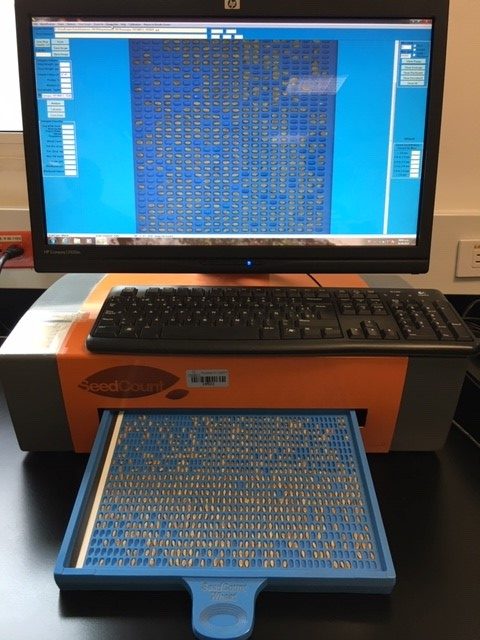

Screening for disease

A native of the Punjab state of India, Randhawa joined CIMMYT as a Post-doctoral Fellow in Wheat Rust Resistance Genetics in 2015. He now works as a CIMMYT scientist and manages the Stem Rust Screening Platform in Njoro, Kenya, which supports screening against stem rust of up to 50,000 wheat lines per year from as many as 20 countries. Over the last 10 years about 650,000 wheat lines have been evaluated for stem rust resistance at the facility.

“The platform’s main focus is on evaluation of wheat lines against the stem rust race Ug99 and its derivative races prevalent in Eastern to Southern Africa, the Middle East and Iran,” explains Randhawa. Ug99 is a highly virulent race of stem rust, first discovered two decades ago in Uganda. The race caused major epidemics in Kenya in 2002 and 2004.

“East African highlands are also a hotspot for stripe wheat rust so, at the same time, we evaluate wheat lines for this disease,” adds Randhawa.

The facility supports a shuttle breeding scheme between CIMMYT Mexico and Kenya, which allows breeders to plant at two locations, select for stem rust (Ug99) resistance and speed up the development of disease-resistant wheat lines.

“Wheat rusts in general are very fast evolving and new strains are continuously emerging. Previously developed rust-resistant wheat varieties can succumb to new virulent strains, making the varieties susceptible. If the farmers grow susceptible varieties, rust will take on those varieties, resulting in huge yield losses if no control measures are adopted,” explains Randhawa.

Helping and sharing

For Randhawa, helping farmers is the main goal. “Our focus is on resource-poor farmers from developing countries. They don’t have enough resources to buy the fungicide. Using chemicals to control diseases is expensive and harmful to the environment. So in that case we provide them solutions in the form of wheat varieties which are high yielding but they have long-lasting resistance to different diseases as well.”

Under the Borlaug Global Rust Initiative, Randhawa and his team collaborate with KALRO to facilitate the transfer of promising wheat lines with high yield potential and rust resistance to a national pipeline for soon-to-be-released wheat varieties.

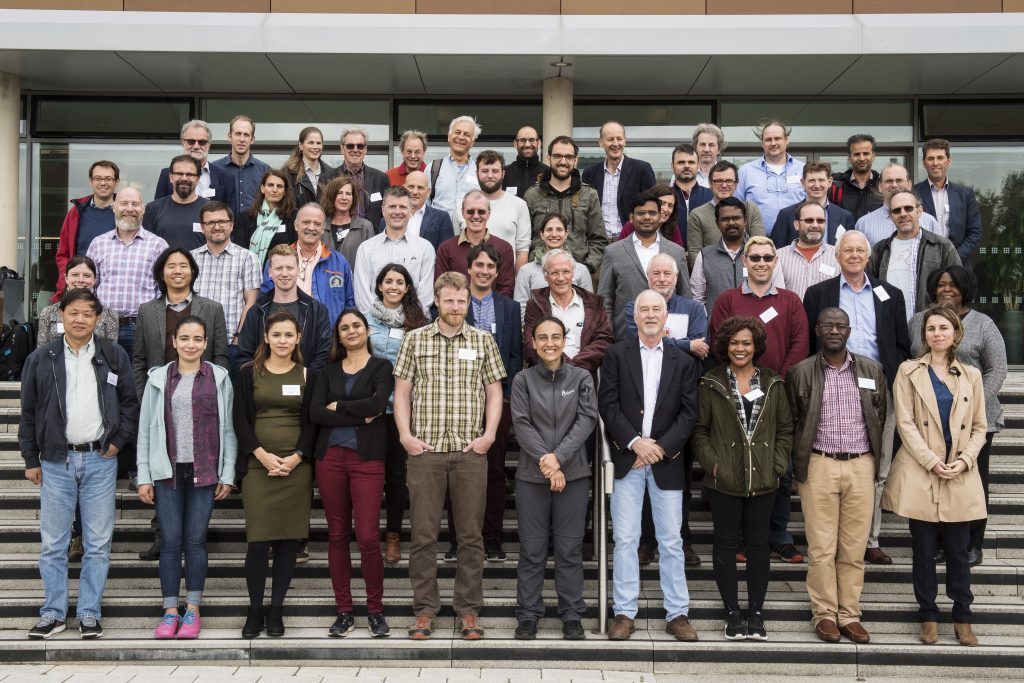

When he is not screening for wheat rusts diseases, Randhawa also organizes annual trainings on stem rust diagnosis and germplasm evaluation for young wheat breeders and pathologists from developing countries. More than 220 wheat researchers have been trained over the last decade.

A farmer at heart

Randhawa always had an interest in agricultural science. “Initially, my parents wanted me to be a medical doctor, but I was more interested in teaching science to school students,” he says. “Since my childhood, I used to hear of wheat and diseases affecting wheat crops, especially yellow rust — which is called peeli kungi in my local language.” This childhood interest led him to study wheat genetics at Punjab Agricultural University in Ludhiana, India.

His mentors encouraged him to pursue a doctorate from the Plant Breeding Institute (PBI) Cobbitty at the University of Sydney in Australia, which Randhawa describes as “the mecca of wheat rust research.” He characterized two new stripe rust resistance genes formally named as Yr51 and Yr57 from a wheat landrace. He also contributed to the mapping of a new adult plant stem rust resistance gene Sr56.

Coming from India, his move to Australia was a pivotal moment for him in his career and his identity — he now considers himself Indian-Australian.

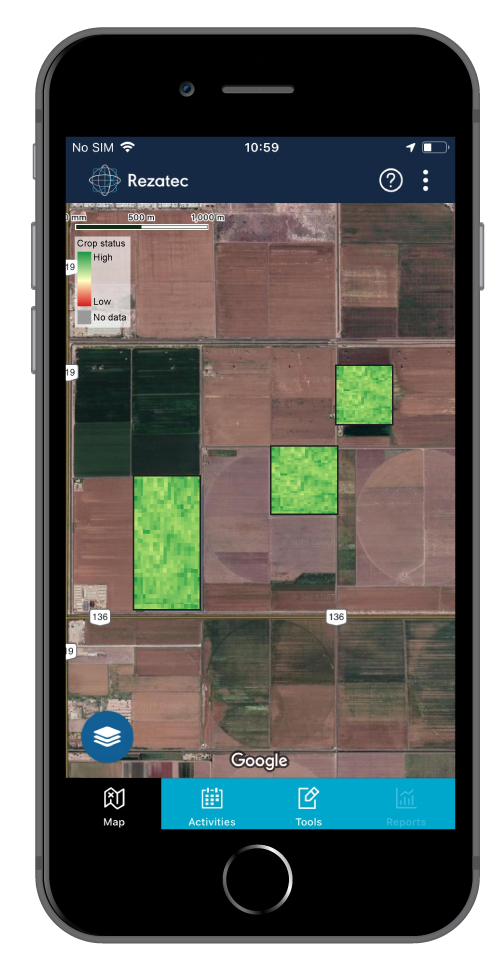

If he had not become a scientist, Randhawa would be a farmer, he says. “Farming is my passion, as I like to grow crops and to have rich harvest using my scientific knowledge and modern technologies.”

At CIMMYT, Randhawa has a constant stream of work identifying and characterizing new sources of rust resistance. “Dealing with different types of challenges in the wheat field is what keeps me on my toes. New races of diseases are continuously emerging. As pests and pathogens have no boundaries, we must work hand-in-hand to develop tools and technologies to fight fast evolving pests and pathogens,” says Randhawa.

He credits his mentor Ravi Singh, Scientist and Head of Global Wheat Improvement at CIMMYT, for motivating him to continue his work. “Tireless efforts and energetic thoughts of my professional guru Dr. Ravi Singh inspire and drive me to achieve research objectives.”