New publications: Caste-gender intersectionalities in wheat-growing communities in Madhya Pradesh, India

A new study has revealed how the ways in which caste and gender interact in wheat systems in India are changing over time, how women struggle to be involved in decisions on wheat farming, how agricultural mechanization is pushing women of all castes out of paid employment, and how women’s earnings are an important source of finance in wheat.

There is growing awareness that not all rural women are alike and that social norms and technological interventions affect women from different castes in distinct ways. The caste system in South Asia, which dates back over 3,000 years, divides society into thousands of hierarchical, mostly endogamous groups. Non-marginalized castes are classified as “general caste” while those living in the social margins are categorized as “scheduled caste” and “scheduled tribe”. Scheduled caste and scheduled tribe farmers face both social and economic marginalization and limited access to information and markets, despite government efforts to level up social inequalities.

In India, women of all castes are involved in farming activities, although their caste identity regulates the degree of participation. General caste women are less likely to be engaged in farming than women of lower castes. Despite their level of participation across caste groups, women are rarely recognized as “farmers” (Kisan) in Indian rurality, which restricts their access to inputs, information and markets.

Gender experts from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and partners investigated caste-gender relations among wheat farmers in Madhya Pradesh, India’s second-largest state by area. The team conducted focus group discussions and interviews in a village community, and carried out a review of GENNOVATE research in the same area. The team also carried out a survey involving about 800 wheat farmers from 18 village communities across the state.

The study, published last month in Gender, Technology, and Development, revealed five key findings:

First, caste distinctions are sharp. There is little interaction between women and men farmers from the scheduled caste category — even between subcastes in this category — and other castes. They live in separate enclaves, and land belonging to scheduled caste farmers is less fertile than others.

Second, all women are fully involved in all aspects of agricultural work on the family farm throughout the year.

Third, despite their strong participation in farming activities, women across caste groups are normatively excluded from agricultural decision-making in the household. Having said that, the findings were very clear that some individual women experience greater participation than others. Although women are excluded from formal agricultural information networks, they share knowledge with each other, particularly within caste groups.

Fourth, about 20 years ago, women across caste groups were being employed as hired agricultural laborers. Over the past four years, increasing mechanization is pushing many women off the field. While scheduled caste women compensate for the employment loss to a certain degree by participating in non-farm activities, general caste women are not able to move beyond the village and secure work elsewhere due to cultural norms. Women therefore face a collapse in their autonomy.

Fifth, gender poses a greater constraint than caste in determining an individual’s ability to make decisions about farm and non-farm related activities. However, a significant difference exists across the caste groups, presenting a strong case for intersectionality.

Challenging social norms in agriculture

The results of the study show that caste matters in the gendered evaluations of agricultural technologies and demonstrates the importance of studying women’s contributions and roles in wheat farming in South Asia.

In recent years, studies have revealed that women in wheat have more influence on farming decisions than previously thought, from subtle ways of giving suggestions and advice to management and control over farming decisions.

Agriculture in India is also considered to be broadly feminizing, with men increasingly taking up off-farm activities, leaving women to as primary cultivators on family fields and as hired laborers. However, rural advisory services, policy makers, and other research and development organizations are lagging behind in recognizing and reacting appropriately to these gendered changes. Many still carry outdated social norms which view men as the main decision-makers and workers on farms.

Read the full study:

Caste-gender intersectionalities in wheat-growing communities in Madhya Pradesh, India

Funding for this study was provided by the Collaborative Platform for Gender Research under the CGIAR Program on Policies, Institutions, and Markets as well as the International Development Research Center of the Government of Canada, the CGIAR Research Programme on Wheat (CRP WHEAT https://wheat.org/), CIMMYT and the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR). The paper additionally drew on GENNOVATE data collected in India in 2015–16 with financial support from CRP WHEAT. Development of the GENNOVATE research methodology was supported by the CGIAR Gender and Agricultural Research Network, the World Bank, and the CRP WHEAT and CRP MAIZE, and data analysis was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

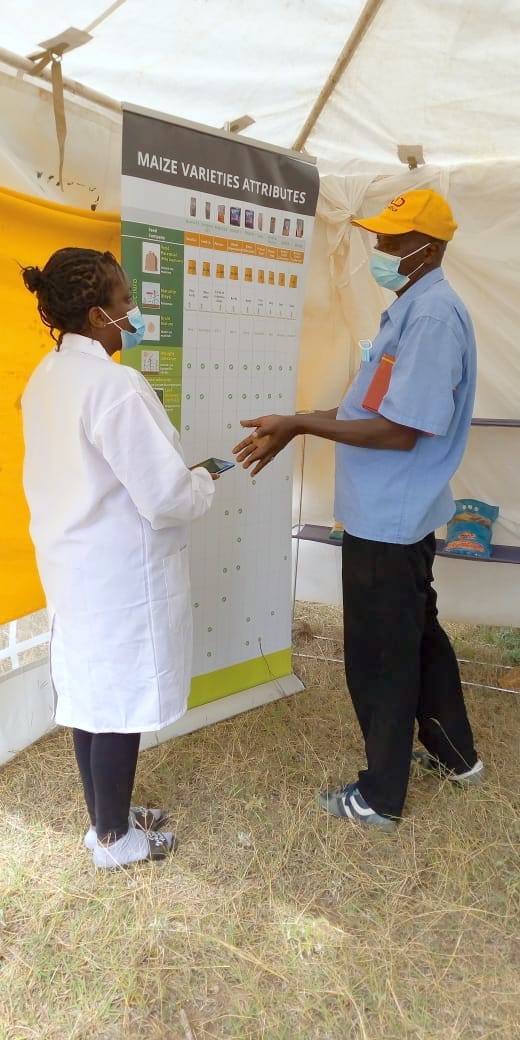

Cover photo: A woman harvests wheat in Madhya Pradesh, India. (Photo: CIMMYT)