Happy Seeder can reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions while making profits for farmers

A research paper published in the world’s leading scientific journal, Science Magazine, indicates that using the Happy Seeder agriculture technology to manage rice residue has the potential of generating 6,000-11,500 Indian rupees (about US$85-160) more profits per hectare for the average farmer. The Happy Seeder is a tractor-mounted machine that cuts and lifts rice straw, sows wheat into the soil, and deposits the straw over the sown area as mulch.

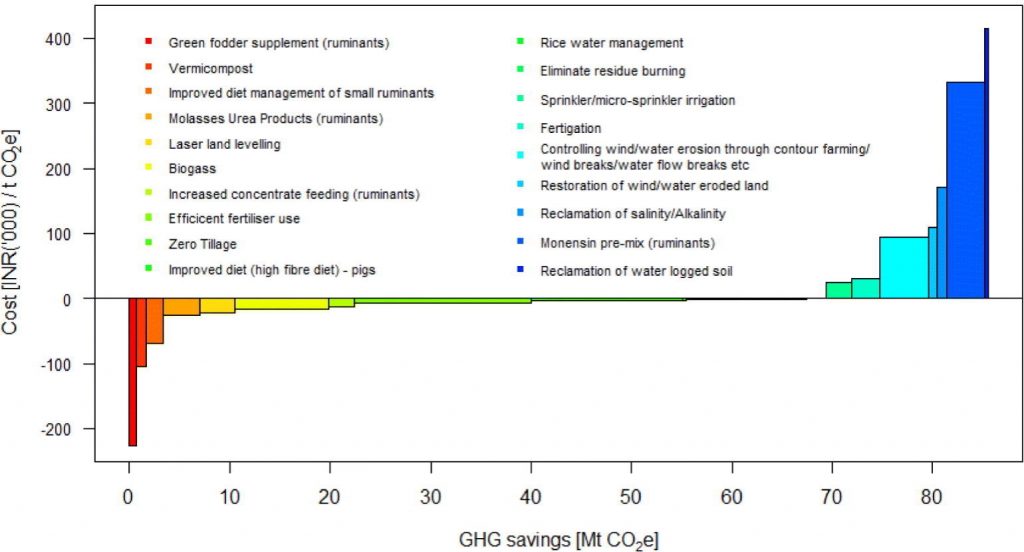

The paper “Fields on fire: Alternatives to crop residue burning in India” evaluates the public and private costs and benefits of ten alternate farming practices to manage rice residue, including burn and non-burn options. Happy Seeder-based systems emerge as the most profitable and scalable residue management practice as they are, on average, 10%–20% more profitable than burning. This option also has the largest potential to reduce the environmental footprint of on-farm activities, as it would eliminate air pollution and would reduce greenhouse gas emissions per hectare by more than 78%, relative to all burning options.

This research aims to make the business case for why farmers should adopt no-burn alternative farming practices, discusses barriers to their uptake and solutions to increase their widespread adoption. This work was jointly undertaken by 29 Indian and international researchers from The Nature Conservancy, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre (CIMMYT), the University of Minnesota, the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), the Borlaug Institute for South Asia (BISA) and other organizations.

Every year, some 23 million tonnes of rice residue is burnt in the states of Haryana, Punjab and Western Uttar Pradesh, contributing significantly to air pollution and short-lived climate pollutants. In Delhi NCR, about half the air pollution on some winter days can be attributed to agricultural fires, when air quality level is 20 times higher than the safe threshold defined by WHO. Residue burning has enormous impacts on human health, soil health, the economy and climate change.

“Despite its drawbacks, a key reason why burning continues in northwest India is the perception that profitable alternatives do not exist. Our analysis demonstrates that the Happy Seeder is a profitable solution that could be scaled up for adoption among the 2.5 million farmers involved in the rice-wheat cropping cycle in northwest India, thereby completely eliminating the need to burn. It can also lower agriculture’s contribution to India’s greenhouse gas emissions, while adding to the goal of doubling farmers income,” says Priya Shyamsundar, Lead Economist at The Nature Conservancy and one of the lead authors of the paper.

“Better practices can help farmers adapt to warmer winters and extreme, erratic weather events such as droughts and floods, which are having a terrible impact on agriculture and livelihoods. In addition, India’s efforts to transition to more sustainable, less polluting farming practices can provide lessons for other countries facing similar risks and challenges,” explains M.L. Jat, CIMMYT cropping systems specialist and a co-author of the study.

“Within one year of our dedicated action using about US$75 million under the Central Sector Scheme on ‘Promotion of agriculture mechanization for in-situ management of crop residue in the states of Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and NCT of Delhi,’ we could reach 0.8 million hectares of adoption of Happy Seeder/zero tillage technology in the northwestern states of India,” said Trilochan Mohapatra, director general of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR). “Considering the findings of the Science article as well as reports from thousands of participatory validation trials, our efforts have resulted in an additional direct farmer benefit of US$131 million, compared to a burning option,” explained Mohapatra, who is also secretary of India’s Department of Agricultural Research and Education.

The Government of India subsidy in 2018 for onsite rice residue management has partly addressed a major financial barrier for farmers, which has resulted in an increase in Happy Seeder use. However, other barriers still exist, such as lack of knowledge of profitable no-burn solutions and impacts of burning, uncertainty about new technologies and burning ban implementation, and constraints in the supply-chain and rental markets. The paper states that NGOs, research organizations and universities can support the government in addressing these barriers through farmer communication campaigns, social nudging through trusted networks and demonstration and training. The private sector also has a critical role to play in increasing manufacturing and machinery rentals.

This research was supported by the Susan and Craig McCaw Foundation, the Institute on the Environment at the University of Minnesota, the CGIAR Research Program on Wheat (WHEAT), and the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). The Happy Seeder was originally developed through a project from the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR).

For more information, or to arrange interviews with the researchers, please contact:

Rodrigo Ordóñez, Communications Manager, CIMMYT

r.ordonez@cgiar.org, +52 (55) 5804 2004 ext. 1167

Sonali Nandrajog, Communications Consultant, The Nature Conservancy – India

sonalinandrajog@gmail.com, +98 9871948044

Spokespersons:

M.L. Jat, Cropping Systems Agronomist, CIMMYT, India

M.Jat@cgiar.org

Priya Shyamsundar, Lead Economist, The Nature Conservancy

priya.shyamsundar@tnc.org

Seema Paul, Managing Director, The Nature Conservancy – India

seema.paul@tnc.org

About CIMMYT

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is the global leader in publicly-funded maize and wheat research and related farming systems. Headquartered near Mexico City, CIMMYT works with hundreds of partners throughout the developing world to sustainably increase the productivity of maize and wheat cropping systems, thus improving global food security and reducing poverty. CIMMYT is a member of the CGIAR System and leads the CGIAR Research Programs on Maize and Wheat, and the Excellence in Breeding Platform. The Center receives support from national governments, foundations, development banks and other public and private agencies.

About The Nature Conservancy – India

We are a science-led global conservation organisation that works to protect ecologically important lands and water for nature and people. We have been working in India since 2015 to support India’s efforts to “develop without destruction”. We work closely with the Indian government, research institutions, NGOs, private sector organisations and local communities to develop science-based, on-the-ground, scalable solutions for some of the country’s most pressing environmental challenges. Our projects are aligned with India’s national priorities of conserving rivers and wetlands, address air pollution from crop residue burning, sustainable advancing renewable energy and reforestation goals, and building health, sustainable and smart cities.