Maize that packs a punch in face of adversity: unveiling new branded varieties for Africa

Even in the best years, significant swathes of sub-Saharan Africa suffer from recurrent drought. Drought wreaks havoc on the livelihoods of millions of Africans – livelihoods heavily leaning on rain-dependent agriculture without irrigation, and with maize as a key staple. And that is not all: drought makes a bad situation worse. It compounds crop failure because its dry conditions amplify the susceptibility of maize in farmers’ fields to disease-causing pests, whose populations soar during drought.

Providing maize farmers with context-specific solutions to combat low yields and chronic crop failure is a key priority for CIMMYT and its partners, such as those in the Water Efficient Maize for Africa (WEMA) Project.

“Our main focus is to give famers durable solutions,” remarks Dr. Stephen Mugo, CIMMYT Regional Representative for Africa and a maize breeder, who also coordinates CIMMYT’s work in WEMA. “These seeds are bred with important traits that meet the needs of the farmers, with ability to give higher yields within specific environments.”

Farmers in Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and South Africa will soon access WEMA’s high-yielding drought-tolerant maize hybrids. In total, 13 hybrids were approved for commercial production by relevant authorities in these countries. These approvals were spread between October 2014 and March 2015 in the various countries.

Kenya’s National Variety Release Committee (NVRC) approved four hybrids in February 2015 (WE2109, WE2111, WE2110 and WE2106), while neighboring Uganda’s NVRC also approved four hybrids at the end of 2014 (WE2101, WE2103, WE2104 and WE2106). Across Uganda’s southern border, in March 2015, the Tanzania Official Seed Certification Institute approved for commercial release WE3117, WE3102 and WE3117. Still further south, South Africa’s Department for Agriculture registered two hybrids (WE3127 and WE3128) in October 2014.

In each country, all the hybrids successfully underwent the mandatory National Performance Trials (NPTs) and the Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability (DUS) tests to ascertain their qualities and suitability for use by farmers.

Varieties that pack a punch

In Kenya, these new WEMA varieties boast significantly better yields when compared to varieties currently on the market as well as to farmer varieties in drought-prone areas of upper and lower eastern, coastal, central and western Kenya.

And that is not all: across them, the new hybrids also have resistance to rampant leaf diseases like maize streak virus, turcicum leaf spot and gray leaf spot.

Dr. Murenga Mwimali of the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization, who is also WEMA’s Country Coordinator in Kenya, explains: “These hybrids are expected to give farmers an average yield of three tonnes per hectare in moderate drought and eight tonnes in good seasons. These are better seeds that will help Kenyans fight hunger through increased productivity.” According to the UN Food and Agricultural Organization, Kenya’s national average productivity in 2013 was a meager 1.6 tonnes per hectare. This compares poorly with South Africa’s 6 tonnes, Egypt’s 9 tonnes and USA’s 9–12 tonnes, as generally reported in other statistics.

Where to find them

The seed of these new varieties should be available in the market once selected seed companies in Uganda and Tanzania produce certified seeds by end of August 2015.

Dr. Allois Kullaya, WEMA Country Coordinator in Tanzania, applauded this achievement and the partnership that has made it possible. “Through the WEMA partnership, we have been able to access improved seed and breeding techniques. The hybrids so far released were bred by our partner CIMMYT and evaluated across different locations. Without this collaboration, it would not have been possible to see these achievements.” said Dr. Kullaya.

In South Africa, close to 10,000 half-kilo seed packs of WE3127 were distributed to smallholder farmers to create awareness and product demand through demonstrations to farmers and seed companies.

This seed-pack distribution was through local extension services in the provinces of Eastern Cape, Free State, KwaZulu–Natal, Limpopo, Mpumalanga and North-West.

Three seed companies also received the hybrid seed to plant and increase certified seed for the market.

Where it all begins – the CIMMYT ‘cradle’, crucible and seal for quality assurance

“In the WEMA partnership, CIMMYT’s role as the breeding partner has been to develop, test and identify the best hybrids for yield, drought tolerance, disease resistance and adaptability to local conditions,” says Dr. Yoseph Beyene, a maize breeder at CIMMYT and WEMA Product Development Co-leader.

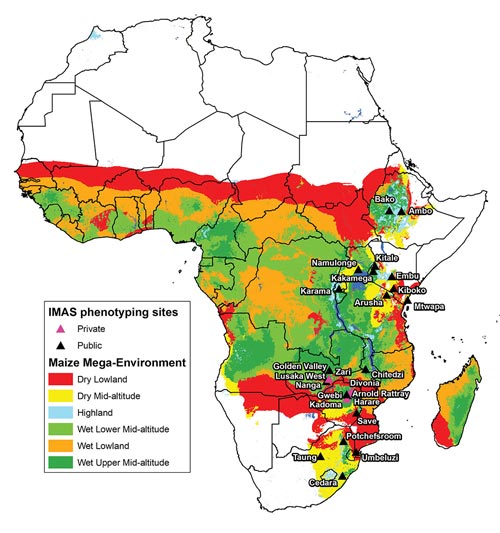

To do this, more than 10, 000 new hybrids combinations are evaluated each year to identify new hybrids that will perform most consistently in various conditions. Hybrids that look promising are subjected to a rigorous WEMA-wide area testing. Only those that pass the test get the CIMMYT nod and ‘seal of approval’. But the tests do not end there: for independent and objevhe verfication, the final test is that these select few advance to – and are submitted for – country NPTs.

Dr. Beyene explains: “Because of these rigorous testing, hybrids that are adapted in two or three countries have been identified and released for commercial production to be done by regional and multinational seed companies which market hybrids in different countries. This eases the logistics for seed production, distribution and marketing.”

How to recognize the new varieties – distinctive shield against drought

All the hybrids released under the WEMA project will be sold to farmers under the trade-name DroughtTEGO™. ‘Tego’ is Latin for cover, protect or defend. The African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF), which coordinates the WEMA Project, has sub-licensed 22 seed companies from the four countries to produce DroughtTEGO™ seeds for farmers to buy.

WEMA’s achievements are premised on a powerful partnership of scientists from CIMMYT, national agricultural research institutes from the five WEMA target countries (Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Mozambique and South Africa), AATF and Monsanto.

WEMA is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the United States Agency for International Development and the Howard G. Buffet Foundation.

Links: More on WEMA | WEMA 2015 annual meeting in Mozambique | Insect Resistant Maize in Africa Project (completed in 2014)

CIMMYT wishes to announce that the start of the planting season for the 2015A planting season at the KALRO–CIMMYT

CIMMYT wishes to announce that the start of the planting season for the 2015A planting season at the KALRO–CIMMYT

A public-private partnership that, along with CIMMYT, involves national research organizations such as the Kenya Agricultural & Livestock Research Organization (

A public-private partnership that, along with CIMMYT, involves national research organizations such as the Kenya Agricultural & Livestock Research Organization (